Encyclopedia

Deportation of Meskhetian Turks, Kurds, Hemshins, Lazes, and other peoples from Southern Georgia in 1944

Among the numerous acts of inhuman cruelty of the Stalinist regime, the large-scale forced relocations of people stand out particularly. Entire ethnic groups were forcibly relocated by state security agencies to remote regions, often to much worse living conditions. The deportation of Meskhetian Turks, as well as Kurds, Hemshins, Lazes, and other ethnic groups from Southern Georgia in 1944, was one of the many forced relocations organized by Soviet authorities during World War II.

The Meskhetian Turks, Hemshins, Kurds, and Lazes were peoples who predominantly lived in the territory of Georgia and the Georgian-Turkish border.

The Meskhetian Turks (self-designation: Ahıska Türkleri — Ahiska Turks) had lived in this territory since 1829. Having Georgian origins (the Meskhi tribes), they were under Turkish rule for a long time, leading to their Turkish identity’s formation. They bore Turkish names, spoke the Turkish language, and were Sunni Muslims. The Soviet authorities first repressed these people between 1928 and 1937, forcing them to change their national self-identification and adopt Georgian surnames, while also repressing and executing their intelligentsia.

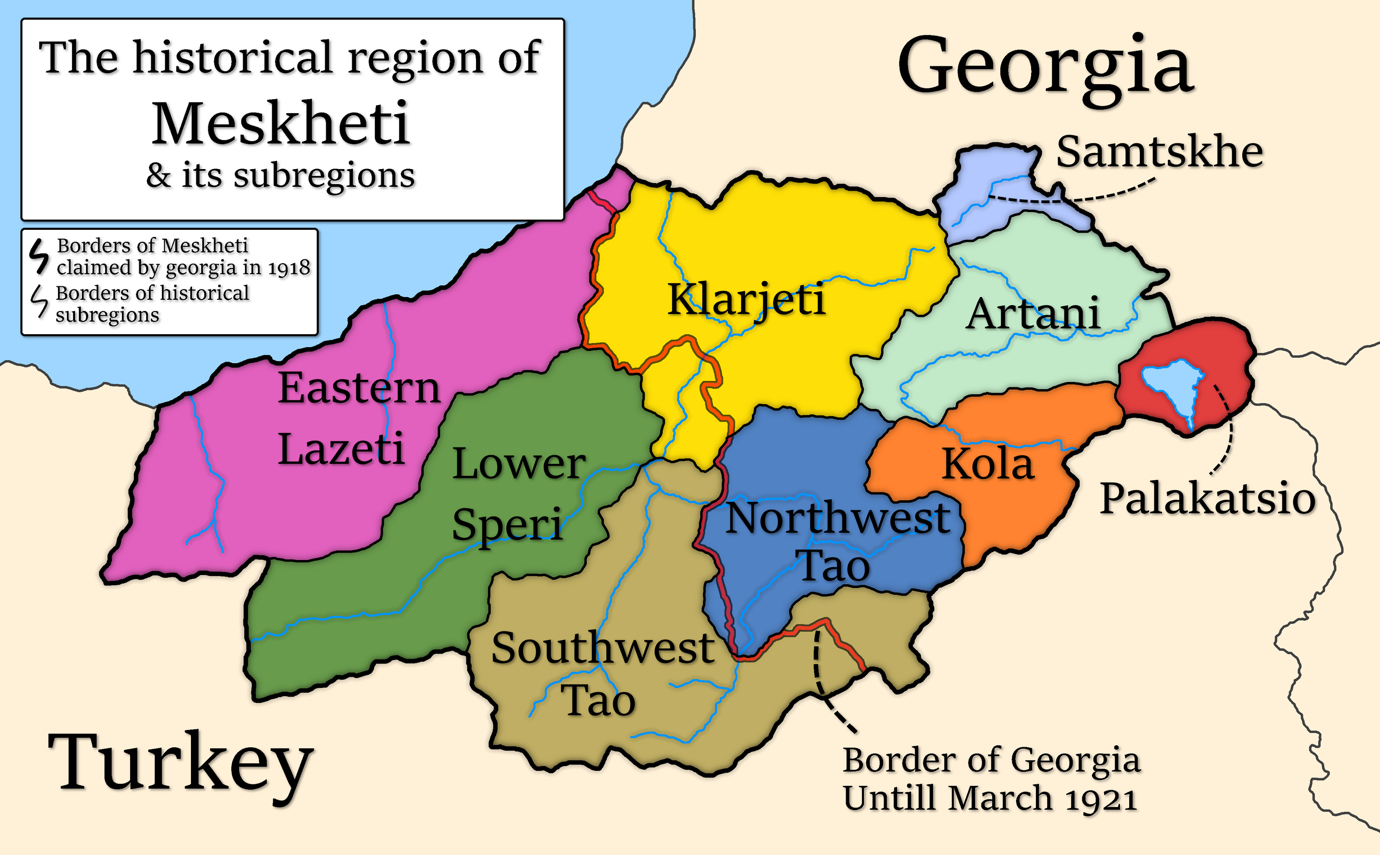

Map of Meskhetia region

On 15 November 1944, the Soviet leadership began the deportation of over 115,000 people from Southern Georgia, specifically from the Meskheti-Javakheti region, to Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The reasons for this deportation included:

- Accusations of disloyalty: The Soviet government suspected many ethnic minorities of disloyalty and potential collaboration with the enemy during World War II.

In a letter to Stalin dated November 28, 1944, Lavrentiy Beria claimed that the population of Meskheti, “…having kinship relations with the inhabitants of Turkey, engaged in smuggling, exhibited emigration sentiments, and served as a source of recruitment for Turkish intelligence agencies for spies and the formation of bandit groups.”

However, evidence suggests otherwise, as over 40,000 Meskhetian Turks fought against Nazi forces on the side of the Soviet army, with the majority of them – around 26,000 – perishing in the war. - Strategic location: Southern Georgia, located near the Turkish border, was considered a strategically important area. The Soviet authorities wanted to “cleanse” these areas of potentially unreliable elements.

- Soviet policy: This deportation was part of Stalin’s broader policy of relocating people to strengthen central control over national minorities.

The issue of deportation from the border areas with Turkey arose in the spring of 1944. At that time, it involved approximately 77,500 people who were planning to be relocated to the regions of Eastern Georgia. However, on July 24, 1944, Beria, in a letter to Stalin, proposed resettling 16,700 households of “Turks, Kurds, and Hemshins” from the border areas of Georgia to the Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Uzbek SSRs. On July 31, a decision was made to relocate 76,021 Turks (later joined by an additional 3,180 people), as well as 8,694 Kurds and 1,385 Hemshins. They were to be replaced by 7,000 peasant families from the underpopulated areas of Georgia and 20,000 border guards.

The Course of Deportation

The People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR, Lavrentiy Beria, detailed the deportation process in the “Instruction on the procedure for resettlement from the border regions of the Georgian SSR of Meskhetian Turks, Kurds, and Hemshins.”

Before the operation began, an authorized district officer inspected the blockades, ambushes, and surrounding areas of the settlement, ensuring that the villages were guarded by troops to prevent anyone from escaping deportation. He then convened a meeting of the adult male population and announced the “resettlement” to Central Asia to improve border security. Following this announcement, the individuals subject to deportation were allowed to gather their belongings.

District officers sent operational groups to the houses. The group leader demanded the surrender of weapons and conducted a search of the premises. Deportees were allowed to take personal valuables, money, household items, and up to 1,500 kg of food per family. The operational worker filled out registration cards for each family.

All individuals in the houses were detained. Turks, Kurds, and Hemshins from the designated areas were subject to deportation, while others were released after their documents were checked. The deportees were then escorted to the railway for transportation.

Beria described the conditions under which people were to be deported, including proper nutrition, medical assistance, and a limit of 30 people per train car. Each train echelon was to be accompanied by a convoy of 25 NKVD officers.

However, according to eyewitness accounts, there was no proper care during the journey. Many deportees died during the trip and while adapting to a completely different climatic zone. Meskhetian Turk Sh. Dursunov, in a letter to the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, Bulganin (1956), wrote:

“The deportees traveled without food, without clothing, under guard, in semi-destroyed wagons, with no heating; many died from the cold and hunger” [1, p. 178].

Deportee Nizam Aliyev also recalled the harsh conditions and lack of food: “About 18 families were loaded into each wagon. At rare stations, soldiers told us to prepare buckets and some baskets for bread. Each wagon was given two or three loaves of bread and half a bucket or a bucket of some kind of soup. They started feeding us only in Makhachkala. We were then dispersed to different places by four echelons: some ended up in Mirzachul, others in Syrdarya, and others in Velikooleksiyivsk. The fourth echelon stopped at the final destination of Zolotaya Orda. And everywhere, it was a hungry steppe. The journey took 28 days. It was already true winter. Not everyone made it: many were left lying along the long road” [7].

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update

Life in Special Settlements

According to a report by M. Kuznetsov, the head of the NKVD special settlements department, and V. V. Chernyshov, the deputy people’s commissar of internal affairs of the USSR, a total of 92,307 people were deported: 18,923 men, 27,399 women, and 45,985 children under 16 years old. They were sent to the Uzbek SSR (53,133 people), the Kazakh SSR (28,598), and the Kyrgyz SSR (10,546). Of all the arrivals, 84,596 were employed in collective farms, 6,316 in state farms, and 1,395 in industrial enterprises. During the journey, 457 died. [4]

After the deportation, people found themselves under strict control by the commandant’s office, which did not allow them to leave the village. Those who violated the regime faced severe punishment—25 years of hard labor without trial or investigation. Many deportees were sent to Siberia. Every ten days, everyone—old people, men, women, and children—had to go to the commandant’s office to register. Nightly checks at homes were frequent. This harsh regime lasted until 1956. Half of those deported to Siberia never returned; they either died or went missing.

Additionally, the issue of household plots was not resolved. Only 800 families received gardens to grow vegetables for sustenance. A total of 6,435 families (27,639 people) from the Georgian SSR were settled in the Kazakh SSR. [1, p. 177]

Deported Simizar Mehmetoglu recalled: “I don’t remember my father at all. I don’t know what he was like. We went through tough times. For six years, I worked hard in Uzbekistan. I drank dirty water. As a result, I developed kidney stones. I still suffer from this… Every time I think about those events, I start trembling. I arrived in Uzbekistan as a child and left as an old woman. There was neither mother nor father. We lived as orphans in Uzbekistan for 40 years” [8].

Simizar Mehmetoglu

In 1956, the Soviet government lifted the restrictions on special settlements and released people from the commandant regime. However, the decree stated that the removal of restrictions did not imply compensation for material losses and did not grant the right to return to the places from which people had been deported. For many years, they did not receive full rehabilitation from the Soviet authorities.

Around 50,000 Meskhetian Turks relocated to Azerbaijan between the 1950s and the 1980s, while most continued to live in Central Asia and Kazakhstan.

In 1989, the Meskhetian Turks faced another tragedy. The Fergana pogroms—a violent ethnic conflict between them and the Uzbeks—occurred. During the events in June, 103 people were killed, including 52 Meskhetian Turks and 36 Uzbeks, with over a thousand people injured or maimed [2].

After the pogroms in Uzbekistan, some Meskhetians moved to Ukraine, settling mainly in the Black Sea region, Tavria, Slobozhanshchyna, and Bessarabia. However, 79 years after the deportation, Russia once again threatens to destroy their homes. The Meskhetian Turks find themselves under Russian occupation or in conflict zones.

The deportation of the Meskhetian Turks, as well as Kurds, Hemshins, Laz, and other ethnic groups from Southern Georgia in 1944, exemplifies the policy of ethnic cleansing carried out by the Stalinist regime. These forced relocations, aimed at strengthening Soviet power and reducing the risk of separatism, led to numerous human tragedies and the loss of cultural heritage.

For decades, Russia has continued the policy of eradicating ethnic minorities using various methods, from deportations to physical destruction. Today, as in the past, these people face persecution and the occupation of their territories.

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk, editor

Sources & references:

- Бугай Н.Ф. Л. Берия – И.Сталину: Согласно Вашему указанию…М.: “АИРО-ХХ” , 1995. – С. 178

- Губернський Б. Ферганська трагедія. Режим доступу: https://ua.krymr.com/a/27039691.html

- Докладная записка наркома внутренних дел Л.П. Берии И.В. Сталину, В.М. Молотову, Г.М. Маленковуо проведении операции по переселению турок, курдов и хемшинов из пограничных районов Грузинской ССР//Бугай Н.Ф. Турки из Месхетии: долгий путь к реабилитации (1944–1994). М.: Изд. дом «РОСС», 1994. С. 76–77. Режим доступу: https://www.alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues-doc/1022541

- Из докладной записки начальника отдела спецпоселений НКВД СССР М. Кузнецова и зам. народного комиссара внутренних дел СССР В. В. Чернышева на имя народного комиссара внутренних дел СССР Л. П. Берии. Режим доступу: http://militera.lib.ru/docs/0/pdf/sb_ih-nado-deportirovat.pdf

- Из Постановления Государственного Комитета Обороны. Москва, Кремль. Июль 1944 г. Режим доступу: https://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/165679-iz-postanovleniya-gosudarstvennogo-komiteta-oborony-moskva-kreml-iyul-1944-g#mode/inspect/page/1/zoom/4

- Инструкция о порядке проведения переселения из пограничных районов Грузинской ССР турок-месхетинцев, курдов и хемшинов (приложение к приказу НКВД СССР № 001176). Режим доступу: https://www.alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues-doc/1022467

- Так это было: Национальные репрессии в СССР. 1919 – 1952 годы. Репрессированные народы сегодня: Худож. – док.сб./ Ред. – сост. С.У.Алиева: В 3-х т. Т. 3. – Москва: “Инсан”. 1993. Режим доступу: http://www.elbrusoid.org/upload/iblock/b24/b240bb7ec5750c4e77326385e6f48d8f.pdf

- Турки-ахыска не могут стереть из памяти ужасы депортации. Режим доступу: https://www.trtavaz.com.tr/haber/rus/avrasyadan/turki-akhyska-ne-mogut-steret-iz-pamyati-uzhasy-deportatsii/618fd67601a30a91f82aebd3