Deportation of Armenians from Crimea

This article examines the history of Armenians in Crimea and the tragic deportations they faced, focusing on the mass resettlements of 1778 and 1944, their causes, conditions, and consequences.

Encyclopedia

The history of Bulgarians in Crimea is long and plays an important role in shaping the ethnocultural landscape of the peninsula. According to various sources, Bulgarians first appeared in Crimea in the late seventh or early eighth century, arriving from the Azov region. They settled in the steppe and foothill areas of the peninsula [1].

The first mass wave of systematic Bulgarian resettlement to Crimea occurred in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (1802–1806), when many fled the Ottoman Empire due to persecution and sought protection in the Russian Empire. They established the first three colonies in Stary Krym, Kyshlav (now Kurske), and Bala-Chokratsi. The area of Stary Krym where the Bulgarians settled became known as Bulgarskaya Zemlya (“Bulgarian Land”), a name frequently cited in historical sources [2].

The second wave of Bulgarian migration took place during the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829. Their communities expanded in Stary Krym, Kyshlav, Feodosia, Kerch, Yevpatoria, and Karasubazar [3].

The third wave occurred in the 1860s, when Bulgarians again tried to escape pressure from the Ottoman Empire. In the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Bulgarian population in Crimea increased further due to internal migration from the northern regions of the Taurida Governorate. It is also noteworthy that Bulgarians and other colonists enjoyed a distinct legal status and were exempt from taxes and certain obligations [4].

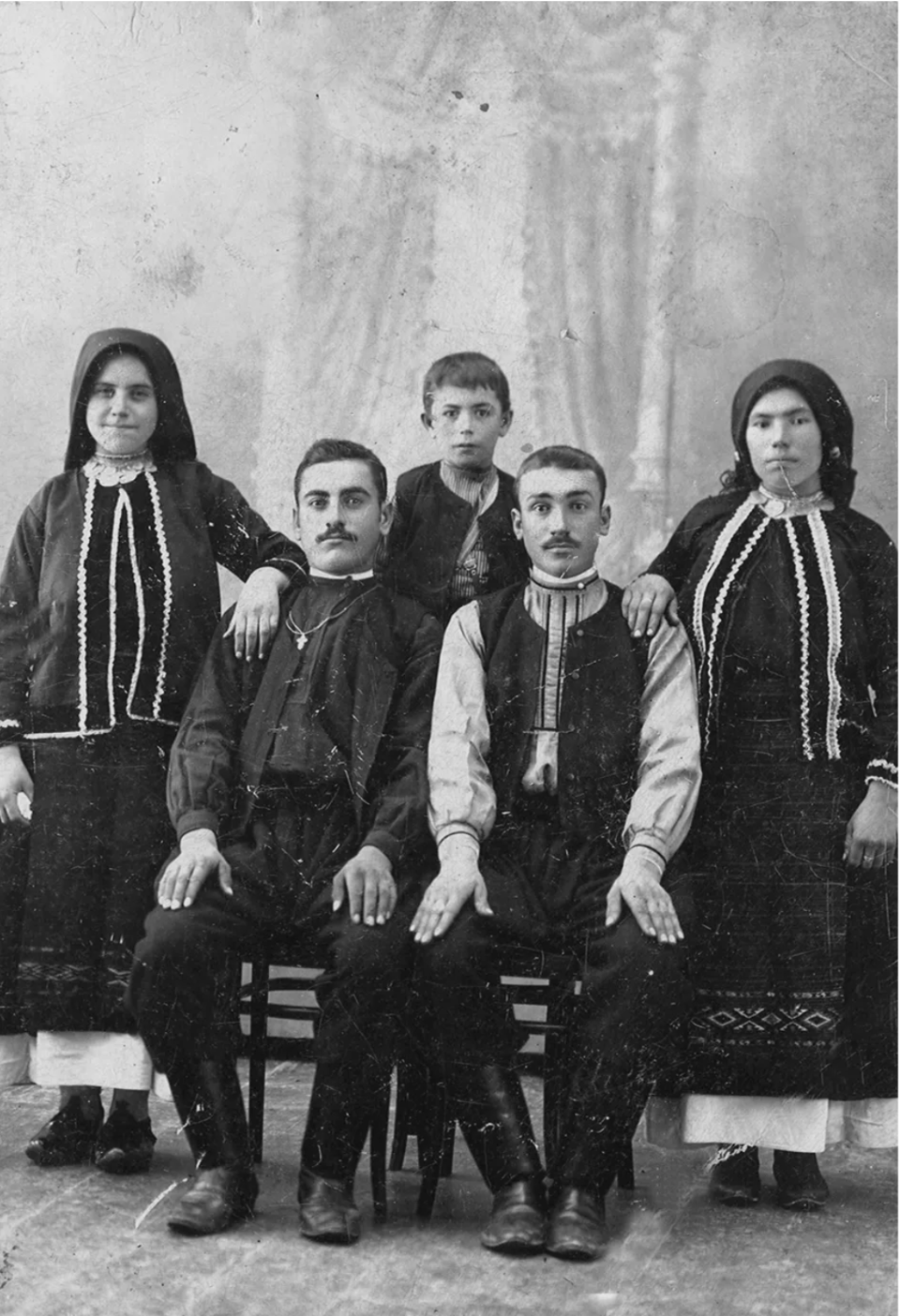

Bulgarians of Crimea from the village of Kyshlav in traditional costumes. Photo – early 20th century from the collections of the Crimean Ethnographic Museum. Photo source: https://crimea-is-ukraine.org/

The deportation of ethnic Bulgarians from Crimea in 1944 was part of a large-scale campaign by Stalin’s communist regime to ethnically cleanse the peninsula on the basis of fabricated accusations of collaboration with Nazi authorities during the German occupation of Crimea in 1941–1944. In total, the Soviet authorities forcibly expelled about 12,500 Bulgarians from Crimea. This crime took place alongside the deportation of Greeks, Armenians and other ethnic minorities.

The deportation unfolded as follows: early in the morning of 27 June 1944, operatives of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, broke into homes, giving people just 15 minutes to pack before forcing them onto trucks. The entire operation took just over a day. By 10 a.m. on 28 June, more than 40,000 people had been loaded onto 17 train echelons; 12 of them had already departed for exile in remote regions of the USSR, while the remaining trains waited their turn. The deportees were sent to the Uzbek SSR and to eastern regions of the Soviet Union as “special settlers”. Separately, 139 people classified by the authorities as “anti-Soviet elements” were arrested and sent directly to Gulag camps [5].

The Stalinist regime justified the deportation with claims of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers and mass desertion, although numerous documents show these accusations to have been unfounded. Bulgarian families were removed without any real evidence of wrongdoing.

The deportation process resembled the operation carried out against the Crimean Tatars: residents were taken from their homes at gunpoint, loaded into freight wagons and given only minutes to gather their belongings. The entire population — regardless of age or gender — was deported without exception, and only a fraction survived the journey and subsequent conditions. The places of exile were remote regions of the USSR, including the Mari ASSR (now the Republic of Mari El), Kirov Oblast, Molotov Oblast (now Perm Krai), Sverdlovsk Oblast and the Bashkir ASSR (now Bashkortostan). A small group was even deported to Kemerovo Oblast, near southern Siberia. The destinations depended largely on the NKVD’s logistical capabilities — how many trains were available and where they could be sent.

Melania Ducheva, a Bulgarian from Crimea, recalled the deportation:

“It was at dawn, around four in the morning. We woke up and didn’t understand what was happening. Soldiers were standing there saying we had 15 minutes to get ready. Then they loaded us onto carts and took us to the station, where they put us into the wagons and took us away… The wagons, of course, were not passenger carriages but so-called ‘cattle cars’ for transporting livestock. There were small windows under the roof, some bunks, and very little space. There was a catastrophic shortage of food, and we ate only what we had managed to grab from home. My mother, trying to feed us children, ran out at one of the substations to exchange her gold ring for milk and some bread — she almost missed the train… We cried, but when we saw her, we shouted: ‘Mum brought us bread and milk!’” [6].

The deportation of ethnic Bulgarians from Crimea has been preserved in the testimonies of the children and grandchildren of those unjustly expelled from their native land. Yuri Palichev, a descendant of Crimean Bulgarians deported during the Second World War, described how the trauma lingered:

“My father was deported and carried this trauma throughout his entire life. For example, I remember him speaking to my grandmother in Bulgarian, but when I came near, they immediately switched to Russian. When I was 16, I asked my father what I should write in my passport — Bulgarian or Ukrainian? He told me I was Ukrainian, not Bulgarian, because my mother was Ukrainian. At the time, I didn’t fully understand why we couldn’t speak about our Bulgarian roots. Later, I realised they were afraid. As an adult, when we were having lunch one day, I asked him, ‘Dad, were you deported?’ The moment he heard this, he burst into tears and left the room…” [7].

The deportation of Bulgarians from Crimea left a deep scar on the memory of the community and forms part of the broader history of repression carried out by the Soviet totalitarian regime against ethnic minorities in Crimea in the 1940s.

The Soviet system dealt mercilessly with the fate of the Crimean Bulgarians who were expelled from their native lands. The deportees were assigned the status of “special settlers” for life, without the right to return; any attempt to escape was punishable by up to 20 years of hard labour. This effectively turned the Bulgarians of Crimea into a semi-category of “second-class citizens” within the USSR. Mortality during transportation was high due to unsanitary conditions and starvation. Many more died in the early years of exile as a result of disease, hunger, harsh climate and the gruelling labour imposed in the special settlements.

As a result, the deportation led to the destruction of the compact Bulgarian settlements in Crimea (Stary Krym, Kyshlav, Bulharshchyna and others), dramatically reducing the proportion of Bulgarians in the peninsula’s population. Even after some were able to return in the late Soviet period, the community could not restore its pre-war numbers or settlement geography, which had a severe impact on the ethnographic landscape of the region. Moreover, despite the formal abolition of the special settlement regime in 1956–1957, returning to Crimea remained practically impossible due to housing shortages, bureaucratic obstacles and political restrictions.

This article examines the history of Armenians in Crimea and the tragic deportations they faced, focusing on the mass resettlements of 1778 and 1944, their causes, conditions, and consequences.

The 1937 deportation of around 173,000 ethnic Koreans from the Soviet Far East to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — its causes, forced relocation, and tragic consequences.

This article explores the 1943 deportation of the Kalmyk people under Stalin, detailing its causes, brutal execution, life in exile, and long-term consequences for the Kalmyk nation.

1944 deportation of Meskhetian Turks, Kurds, Hemshins, Lazes, and other ethnic groups from Southern Georgia by the Stalinist regime.

and we will send you the latest news