Encyclopedia

Deportation of Chechens and Ingush in 1944.

The former Soviet Union was a place rife with distrust and paranoia, where officials were always on the hunt for so-called “enemies of the people” and “Nazi accomplices.” This led to frequent forced relocations of those labeled as undesirable. One of the most shocking instances occurred in February 1944, when over 400,000 Chechens were uprooted from their homes by NKVD officers in just eight days. Fast forward to today, and Russia, the Soviet Union’s successor, is leveraging the Chechen population in its war against Ukraine. This behavior underscores the idea that both the Soviet Union and Russia act as colonizers, exploiting the people and resources of the lands they occupy. This article explores why the Soviet Union acted so swiftly and harshly in deporting the Chechens.

Conditions Leading to Deportation

During the German-Soviet war from 1942-1944, the Nazis only briefly occupied a small area in the extreme northwest of Chechen-Ingushetia, then a part of the Soviet Union. However, after the Soviet army expelled the Nazis from the Caucasus, the Soviet leadership accused the Chechens of collaborating with the enemy. Chechen political scientist Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov provides insights into these accusations in his book “Genocide in the USSR: The Murder of the Chechen People.”

According to Avtorkhanov, the Chechens’ ongoing fight for national independence and their rejection of Soviet rule made them a thorn in the side of the Soviet leadership, leading to their repression. Moscow saw the Caucasus as a strategic base for potential conflicts with the West and expected a unified Caucasian resistance against Soviet rule. This led to a policy of population cleansing, aimed at leaving only those deemed “reliable” and unlikely to rebel. The 1944 mass deportation of Chechens was part of a broader strategy to turn the Caucasus into a secure base for expanding influence in Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and India, necessitating the removal of the local population [1,69].

The Soviet leadership’s claim that the Chechens were collaborating with the Nazis during their mass deportation was just a cover-up. The real goal was to use the territory for strategic purposes and then displace its ihabitants under the guise of fabricated reasons.

Pavel Polyan, a renowned historian on Soviet deportations, supports this view, stating that the claims of Chechen collaboration with the Germans were unfounded. He argues, “There was no basis for claiming collaboration because the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was never occupied. The only exception was a part of the city of Malgobek, now in Ingushetia. In other words, there was no situation to reveal any willingness or enthusiasm for cooperating with occupying forces, which were criminal, German, aggressive due to some territory being occupied. There was no occupation» [2].

Operation «Chechevitsa»

Deportation of Chechens and Ingush

Map author: Tahirgeran Umar

Deportation of Chechens and Ingush

Starting at 5:00 am on February 23, 1944, the forced removal of the Caucasus population commenced, excluding those in alpine areas. The deportation involved relocating a total of 493,269 people in 180 train convoys [9]. Archival reports from March 18, 1944, indicate that the planned deportation of Chechens, Ingush, and Balkars was to involve 194 train convoys and 521,247 individuals [15]. Joseph Stalin personally oversaw the deportation process, with Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), sending him confidential telegrams. On March 1, 1944, Beria informed Stalin that over 400,000 people had been successfully deported.

During the journey to their new locations, 56 babies were born, while 1,272 individuals lost their lives.

Eyewitness accounts of these harrowing events have been recorded and preserved. Maryam Musaeva, who was expelled from the village of Starye Atagi in the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, shares her experience: “In Starye Atagi, they announced that Chechens were being evicted by Stalin’s orders. Everyone gathered and started being removed from the village. Three soldiers came to us and asked if there were any adults. I told them I was waiting for my mother and brother, who were working in Grozny at a military plant. The soldiers said not to wait, as they wouldn’t be coming, and began helping me pack. They advised me to take food and warm clothes. I managed to pack corn flour, my mother’s coat and my old father’s fufayka. I also insisted on taking our Singer sewing machine… We reached the outskirts of Grozny. I had hoped to find my mother and my brother there. Each freight car held 10–15 families, and each Chechen family had 6–7 children… It took an entire month for them to reach their deportation destination. They did not stop at stations, only in open areas — to remove the deceased. Where they were buried remains unknown. If they stopped, they stopped only in remote places… They fed us with porridge: one bucket for everyone. My grandfather was with us in the car, he was 95 years old. He took great care of us children, tried to soothe us, told us that a fertile land awaits us, where corn grows taller than a person, and cows produce more than a bucket of milk. The old man could not endure the journey and died en route. The car door opened, and a young soldier stepped in, trembling with cold, eyes full of tears. I felt such pity for him that I offered him my father’s sweatshirt. Later on, at bus stops, this soldier would bring us a bucket of porridge and a loaf of bread, concealing them in his clothing. The road was terrible: hunger, cold, disease, but even in these conditions there were people who sympathized and understood injustice with their hearts” [3, 241].

Mazieva Ashat Ilyasovna, who was among the 400,000 deported Chechens, recalls: “Our entire family was resettled, but we never saw our father again after that day. He was taken away on February 23, pulled from the house half-dressed; later, we were informed that he had been shot. We lived in the village of Ekazhevo, in the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Toward the end of 1943, NKVD representatives began to arrive in our village, already left by soldiers. Rumors circulated around the village that the Ingush were being prepared for deportation. Although everyone was well aware that the Karachai people were deported in 1943, many still believed that such a fate would not befall our people. However, February 23, 1944, arrived. We were given 24 hours to gather our belongings. We all began to cry. When mom asked where we were going, she was very rudely answered and shoved… We hurriedly packed. My parents grabbed a bag of corn, flour, and potatoes; I don’t remember anything else. They carried more items on their persons. The older sister helped my mother, collected the younger ones, they all whimpered. No one resisted; everyone feared being killed… We saw a woman try to run away; a man in uniform struck her in the face, and she fell to the ground. At the time of the resettlement, there were seven people in our family. My Mom, named Zulfia, had six children. The oldest was my sister Elina, born in 1930; I came next, followed by my brother Gaziz born in 1933, then my sister Khadiz in 1937, and the youngest brother, who was only three months old, born in 1943. His name was Gasar; he died en route, from hunger. I remember my mother crying. She didn’t eat anything during the journey, and her milk disappeared. And the baby died… The guards came, searched the car and threw it to the side of the road. This was not uncommon back then, we were treated like animals. It is considered shameful in our culture not to bury the dead, but circumstances forced us to do otherwise” [3, 243].

Ingush Gazdiev family near the body of the deceased daughter.

Kazakhstan, 1944.

Photo source: https://arzamas.academy/mag/934-deportation

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update

Consequences of Deportation

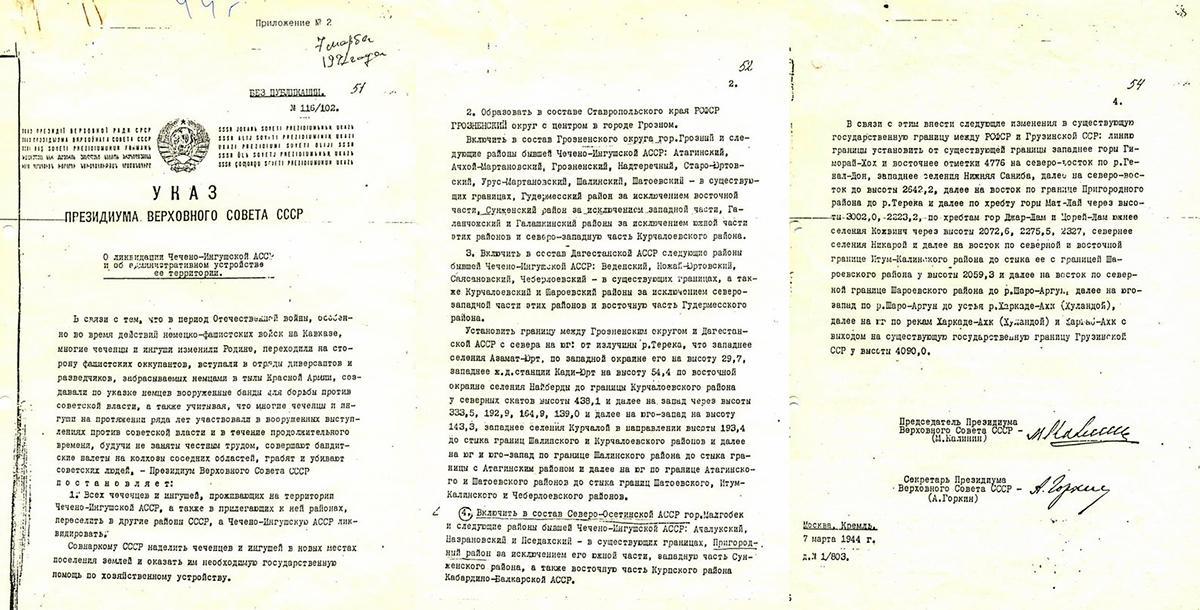

Following the deportations, the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic underwent significant administrative and territorial changes. On March 7, 1944, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree that dissolved the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and established the Grozny Region. This decree consolidated all industrial and several agricultural areas of Chechen-Ingushetia, along with six districts from the Stavropol Territory and the city of Kizlyar — none of which were originally part of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic — into this new region. The remaining territory of the CHI ASSR was divided among the Soviet Union republics of Georgia, North Ossetia, and Dagestan.

After the expulsion of the Chechens and Ingush, only 35% of the original inhabitants remained in the territory of the former Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, primarily consisting of ethnic Russians. To address the demographic shift, the Soviet authorities issued Decree No. 255-74 ss on May 9, 1944, concerning the settlement and development of the areas formerly known as Chechen-Ingushetia. The state’s objective was to populate the newly created Grozny region mainly with immigrants from central Russia. This was part of a broader strategy to strengthen the “Russian” element along the state’s borders and to fulfill the economic development needs of the region. Most of the immigrants to the Grozny region came from the Stavropol Territory and other regions of the North Caucasus.

To erase any memory of the Chechens and Ingush, the Grozny regional committee of the party decided on June 19, 1944, to rename most of the districts and district centers of the region. Names with Chechen origins were replaced by Russian ones. For instance, Achkhoy-Martanovsky district was renamed Novoselsky, Urus-Martanovsky became Red-Army, and Shalinsky was changed to Mezhdurechensky.

In 1948, the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued Order No. 4367-1726ss, mandating the permanent eviction of deportees from their homes and imposing criminal liability for any attempts to return or escape. This order aimed to strengthen the settlement regime for various ethnic groups, including Chechens, Karachaevites, Ingush, Balkars, Kalmyks, Germans, and Crimean Tatars. The Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks approved the order, stating that the resettlement of these ethnic groups to remote areas of the Soviet Union would be permanent, with no right to return to their former residences. Unauthorized departures or escapes from the designated settlement areas would result in prosecution, with the punishment set at 20 years of hard labor [7, 163].

The majority of the Vainakh immigrants, including 239,768 Chechens and 78,470 Ingush, were relocated to Kazakhstan. An additional 70,097 Chechens and 2,278 Ingush were sent to Kyrgyzstan. Chechens were primarily settled in Akmola, Pavlodar, North Kazakhstan, Karaganda, East Kazakhstan, Semipalatinsk, and Alma-Ata regions of Kazakhstan, as well as in Frunze and Osh in Kyrgyzstan. Moreover, hundreds of special settlers who had worked in the oil industry were sent to deposits in the Guryev region [11].

Reaction to the Deportation of Chechens and Ingush

Interestingly, the deportation of the Chechens and Ingush was widely publicized among the Chechen diaspora abroad. In the latter half of 1944, news of the eviction reached the Chechen community in Turkey. Despite the local government’s known suppression of national minorities, it turned a blind eye when Chechens organized religious rites and sought help from fellow tribesmen in response to this tragedy. In Turkey, it was widely reported that the Soviet army had executed many in the mountains and expelled the Chechens from their homeland [8].

Radio Liberty emerged as a powerful platform for exerting pressure against the USSR. Abdurahman Avtorkhanov and Magomed Abdulkerimov regularly spoke on its airwaves about the heinous repression carried out by the Soviet government against its subjugated peoples.

In 1952, Avtorkhanov authored the book “The Murder of the Chechen-Ingush People,” which for years served as a primary source of information in the West about the Soviet government’s crimes against its own people. This book was the first to offer the world a comprehensive view of this horrific tragedy, inspiring other Western historians to write about the tragedy of the deported peoples [8].

The European Parliament’s plenary assembly adopted the Second Amendment on February 26, 2004. This amendment stated that, based on the IV Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention for the Prevention of the Crime of Genocide of 1948, the deportation of the entire Chechen people constituted an act of genocide [12].

In summary, the Soviet authorities’ systematic destruction of an entire people is evident. The Chechen people primarily suffered due to their freedom-loving and independent spirit, which clashed with the communist authorities’ dictatorial model for pacifying peoples. This was not limited to the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic but extended to all the occupied territories. It included forced collectivization, sweeping accusations against entire ethnic groups for supporting the Nazis during World War II, and attempts to artificially develop these regions by deploying party leadership from central Russia.

Despite these losses, the Chechen people managed to return to their native lands and, after decades, resume their armed struggle for independence against Russian invaders. This struggle continues to this day.

Chechnya – Memorial to the Great Terror and Deportations

Chechens and Ingush at the end of World War II, Grozny, 2007 [10]

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Documents:

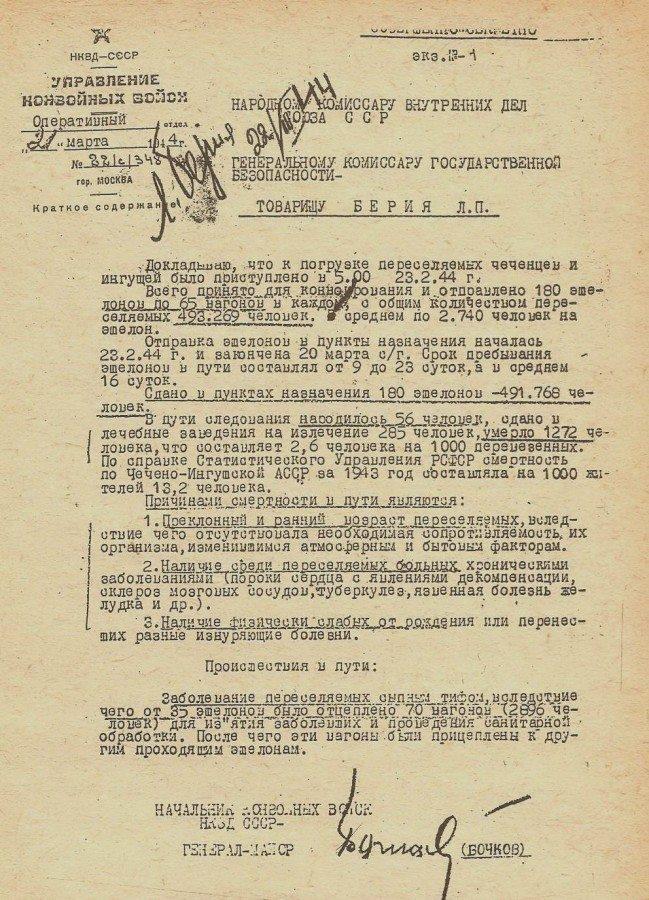

Report on the progress of the deportation of Chechens and Ingush. March 21, 1944. [13].

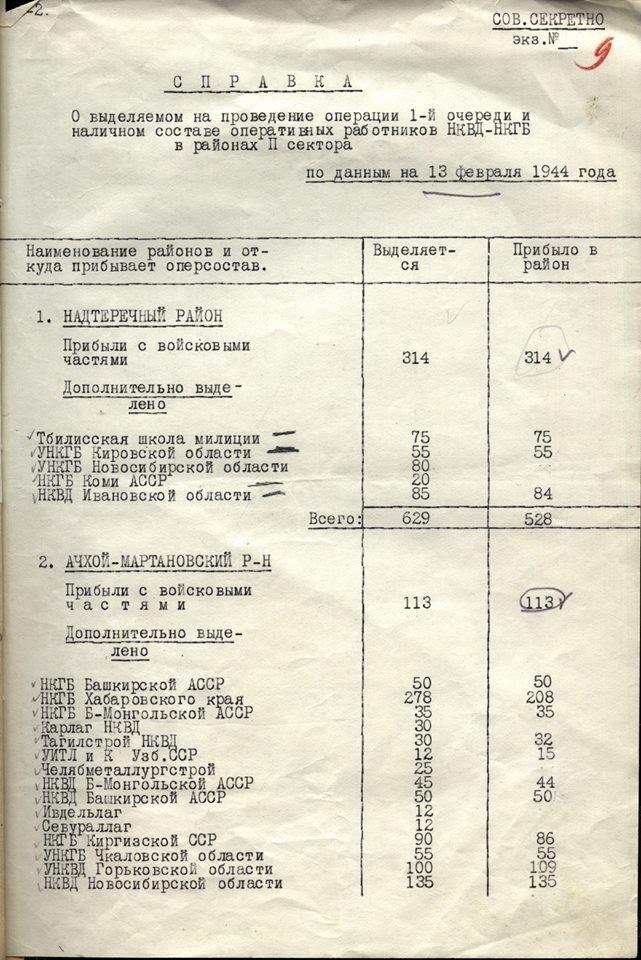

Information on the allocation of a special contingent from the NKVD-NKGB employees for the operation «Chechevitsa» for the deportation of Chechens and Ingush. [13].

Decree on the liquidation of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of March 7, 1944. Photo: Electronic library of historical documents [14].

Sourses & References:

- Авторханов Абдурахман. Народоубийство в СССР. Убийство чеченского народа. Мюнхен, «Свободный Кавказ», 1952.

- Вачагаев Майрбек. Сталинская депортация чеченцев и ингушей. Реальные причины. URL: https://cutt.ly/24E4bVn

- Сактаганова З. Фрагменты воспоминаний депортированных женщин: адаптация и жизнь в Казахстане. Мир Большого Алтая – World of Great Altay 5(2) 2019.

- Шнайдер В. . Освоение территорий упраздненных Национальных автономий Северного Кавказа (середина 1940-х – середина 1950-х гг.) / В. Г. Шнайдер // Кавказский Сборник. – М. : НП ИД «Русская панорама», 2007. –Т. 4 (36) ; под ред. Н. Ю. Силаева. – С. 126–141.

- Макаренко А. І. Депортація чеченців та інгушів як провал стратегії політики Радянського Союзу на Північному Кавказі. Магістеріум. Політичні студії. – 2014. – Вип. 58. – С. 90-96.

- Данлоп Дж. Россия и Чечня: история противоборства. Корни сепаратистского конфликта / Дж. Данлоп ; [пер. С англ. Н. Банчик ; предисл. А. Черкасова].– М. : «Р. Валент», 2001. URL: http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/Magisterium_p_2014_58_20

- Совет Министров СССР. Постановление № 4367-1726 сс. Москва, от 24 ноября 1948 г. // Текущий архив Верховного Совета РФ. Репрессированные народы России: чеченцы и ингуши: Док., факты, коммент. — М.: Капь, 1994.

- Вачагаев Майрбек. Депортация чеченцев и ингушей через призму истории. URL: https://www.kavkazr.com/a/deportation-chechenzev-i-ingushey-cherez-prizmu-istorii/28326372.html

- 23 лютого – день влаштованої Сталіним депортації чеченців та інгушів. URL:https://espreso.tv/news/2019/02/23/23_lyutogo_den_vlashtovanoyi_stalinym_deportaciyi_chechenciv_ta_ingushiv

- Марія Щур. 23 лютого – річниця депортації чеченців та інгушів, трагедія, яку не люблять згадувати в Росії. URL: https://www.radiosvoboda.org/amp/1498044.html

- Депортация чеченцев и ингушей. URL:https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/202258/

- European Parliament recommendation to the Council on EU-Russia relations (2003/2230(INI)). URL: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-5-2004-0121_EN.html

- Операция «Чечевица». 23 февраля 1944 года. URL:https://bessmertnybarak.ru/article/operatsiya_chechevitsa/

- Шкитина А. Как чеченцы и ингуши отмечают 23 февраля. URL:https://s-t-o-l.com/material/36412-kak-chechentsy-i-ingushi-otmechayut-23-fevralya/

- Народный комиссариат внутренних дел СССР. Заместителю наркома Б.3. Кобулову. Отчет о проведении специальных перевозок в связи с выселением чеченцев, ингушей, балкарцев. 18 марта 1944 г. // Ст. Московские новости. 1990. № 41. С. 11; Кабардино-Балкарская правда. 1990, 19 июля.

- Из постановления № 255—74 сс. О заселении и освоении районов бывшей Чечено-Ингушской АССР. 9 марта 1944 года // ГАРФ. Ф. Р-5446. Оп. 47. Д. 4356. Л. 59-62. Репрессированные народы России: чеченцы и ингуши: Док., факты, коммент. — М.: Капь, 1994.