Encyclopedia

Deportation of Transcarpathian Jews in 1944

In unraveling the haunting chapters of history, the deportation of Transcarpathian Jews in 1944 emerges as an indelible scar on the tapestry of humanity. Today, as Russia commits forced deportations of Ukrainians, the echoes of past horrors reverberate with alarming familiarity. Exploring the parallel narratives becomes not only an exercise in historical reflection, but a critical lens through which we can comprehend the gravity of present-day transgressions. This article serves as a timely reminder that the lessons drawn from the past are not confined to history books but are vital tools to comprehend, resist, and ultimately prevent the recurrence of injustice in our contemporary world.

The documented mass resettlement of ethnic Jews to Transcarpathian territory traces back to the 16th century, with a significant influx facilitated by the tolerant policies of Austrian authorities on the national question. By 1850, the Jewish population in historical Transcarpathia had reached 40,000, comprising approximately 10% of the total population [1, p. 4].

Upon the establishment of Hungarian rule in March 1939, the Jewish community emerged as one of the largest national minorities in the region, accounting for 102,542 individuals according to the 1930 census. The majority of the Jewish population resided in rural areas, engaging in agriculture and crafts, a departure from the conventional European Jewish lifestyle. Noteworthy concentrations existed in urban centers like Uzhhorod, Khust, Irshava, and Solotvyno, with Mukachevo serving as the spiritual and cultural hub boasting the largest community [ibid]. In 1930, Mukachevo alone housed 11,313 Jews, constituting 43% of the town’s population, with over 30 synagogues scattered across the region on the eve of the Second World War.

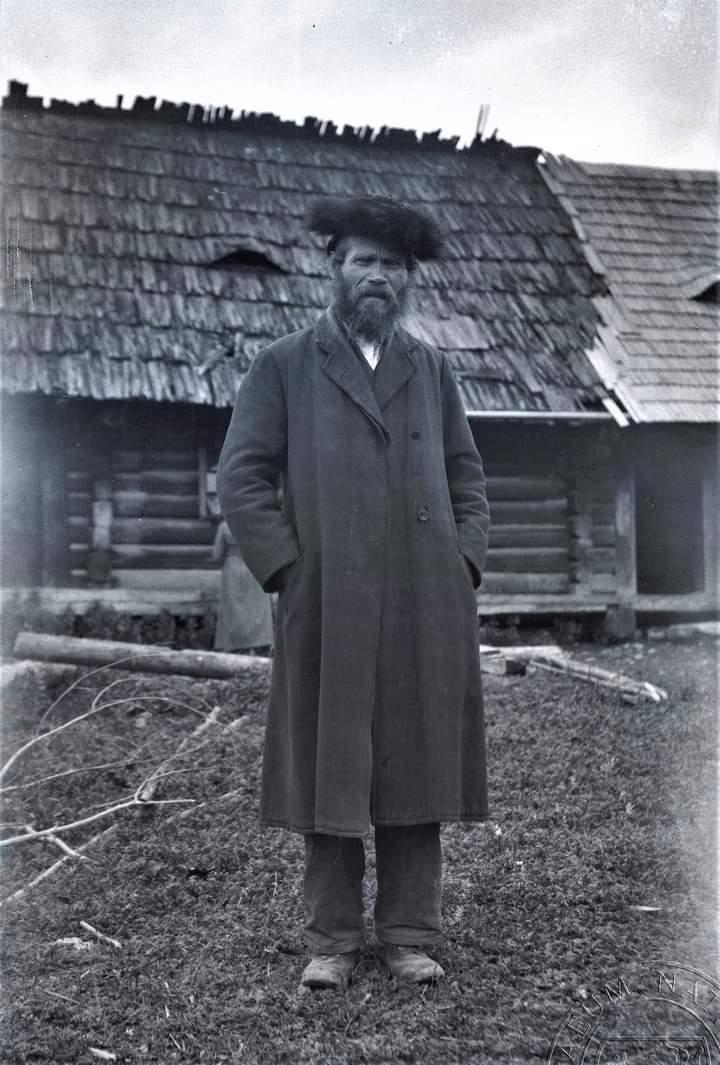

The photograph by Czech photographer Jiří Krala shows a Jewish man in the village of Izky in the Mizhhiria region in the 1920s. From the archive of Mykhailo Markovych.

The onset of the Hungarian occupation in Transcarpathia marked the beginning of anti-Jewish laws, culminating in the passage of several discriminatory acts between 1938 and 1942. These laws significantly curtailed the role of Jews in economic, social, and political life. Particularly impactful was the IV Anti-Jewish Law of July 31, 1942, which restricted Jews from purchasing agricultural land and limited their ownership to no more than 57 hectares [2, pp.112-116]. Local authorities often exploited these regulations, utilizing administrative methods to confiscate land from Jewish owners who refused to comply [1, p.27].

The trajectory towards the deportation of Transcarpathian Jews gained momentum with the implementation of a series of discriminatory laws based on ethnicity. In collaboration with the German military, the Hungarian authorities decided to establish ghettos systematically for the relocation of ethnic Jews. A pivotal meeting on April 7, 1944, at the Hungarian Ministry of the Interior, spearheaded by State Secretaries L. Endre and L. Baki, set the stage for the creation of military districts to coordinate actions for the establishment of ghettos and subsequent deportations [3, p.363]. Priority areas for deportation were identified, with the Carpathian Mountains and northern Transylvania designated as focal points.

The Jews, unaware of their impending destination, were fed false information by local authorities regarding the purpose of the systematic and planned gathering. Testimonies from survivors highlight the misinformation spread, with reassurances of resettlement to Palestine or promises of organized work within the ghettos [6].

By April 1944, twelve ghettos were operational, housing over 100,000 Jews in present-day Transcarpathia. The forced deportation process to one of Europe’s deadliest concentration camps, Auschwitz, commenced, lasting 52 days from April 16 to June 6, 1944. Trains departed from eight stations, transporting 2,000 to 4,000 Jews per train to their final destination. In total, 28 trains departed from the territory of present-day Transcarpathia, with Auschwitz-Birkenau serving as the grim endpoint [4, p.182].

![Arrival of trains with Hungarian Jews at Auschwitz, 1944.Photo from the Auschwitz Album, Yad Vashem [6]](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/image3-e1707390665711.jpg)

Arrival of trains with Hungarian Jews at Auschwitz, 1944.

Photo from the Auschwitz Album, Yad Vashem [6]

In conclusion, the deportation of Transcarpathian Jews in 1944 stands as one of the bloodiest episodes in Holocaust history, profoundly impacting the region. The tragic loss of this ethnic group, integral to the region’s identity and cultural fabric, underscores the need to remember these atrocities and honor the victims, ensuring that such crimes against humanity remain etched in collective memory as a poignant reminder and deterrent against their recurrence. In the shadow of this compelling historical saga lies a stark reminder that the echoes of such atrocities must not be allowed to fade, urging us to reflect on the collective responsibility to ensure that the poignant tales of Transcarpathian Jews resonate with the urgency of preventing history from repeating itself.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk, editor

Transcarpathia, Dragovo village, Jewish cemetery.

Photo source: Мой штетл. Еврейские местечки Украины [8].

Sources & References:

- Славік Ю. Шлях до Аушвіцу: Голокост на Закарпатті. – Дніпро: Український інститут вивчення Голокосту «Ткума», 2017.

- Ваків М. Угорські антиєврейські закони та їх прояви на Закарпатті (1920–1942 рр.)

- Елинек Йешуягу А.. Карпатская диаспора. Евреи Подкарпатськой Руси и Мукачева (1848-1948) / Елинек А. Йешуягу; пер. с англ. М. Егорченко, С. Гурбича, Э. Гринберга, при участии С. Беленького, О. Клименко; фотоматериалы и карты П.Р. Магочия; ред. рус. текста В. Падяк. – Ужгород: Изд-во В. Падяка, 2010. с. 363.– 498 с.

- Славік Ю. Репресивна політика Угорщини на Закарпатті. (1938-1944 рр.). Дисертація на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата історичних наук. Ужгород – 2016. С.174.

- Худіш Павло. Ґеттоїзація та Голокост на Закарпатті у свідченнях жертв і очевидців. (За Матеріалами обласної надзвичайної комісії). Науковий вісник Ужгородського університету, серія «Історія», вип. 1 (42), 2020.

- Худіш Павло. Ґеттоїзація та Голокост на Закарпатті у свідченнях жертв і очевидців.

- Офіцинський Р. Голокост на Закарпатті тривав 52 дні.

URL: https://zakarpattya.net.ua/Zmi/123234-Holokost-na-Zakarpatti-tryvav-52-dni

- Мой штетл. Еврейские местечки Украины.

URL: https://myshtetl.org/zakarpat/khust _dstr.html.