Encyclopedia

Deportations of Chinese (1926–1937) and Executions of Chinese in 1938

The Chinese, like many other peoples living in the USSR, were affected by deportations. From seasonal workers and miners who at the beginning of the 20th century formed a significant part of the economy of Russia’s Primorye region, the community quickly turned into an “unreliable element” in the eyes of the Soviet authorities. Between 1926 and 1936, targeted expulsions from border areas took place, and during the Great Terror of 1937-1938, these deportations were combined with mass arrests and executions.

Project Erased Histories is supported by the European Union under the House of Europe programme.

Reasons for the Appearance of Chinese in the Russian Empire

The proximity of the Russian-Chinese border and the abundance of natural resources in the Far East were the first magnets for settlers. Already in the first half of the 19th century, fugitives from justice, exiles from the Qing Empire, hunters, and traders began to appear there. As researcher Olga Alexeeva notes, it was precisely “hunters, fishermen, ginseng gatherers, and small traders” who made up the first waves of migrants drawn by the riches of the region.[1]

After annexing the Amur and Primorye regions in 1858-1860, Russian authorities even encouraged settlement for some time. Local officials saw the Chinese as pioneers in land reclamation, allowing them to purchase farmland and granting twenty years of tax exemption. This policy quickly increased the size of the community but also generated fears of possible territorial claims from China. By the end of the 19th century, the government began restricting settlement in border areas and introduced a system of special permits.

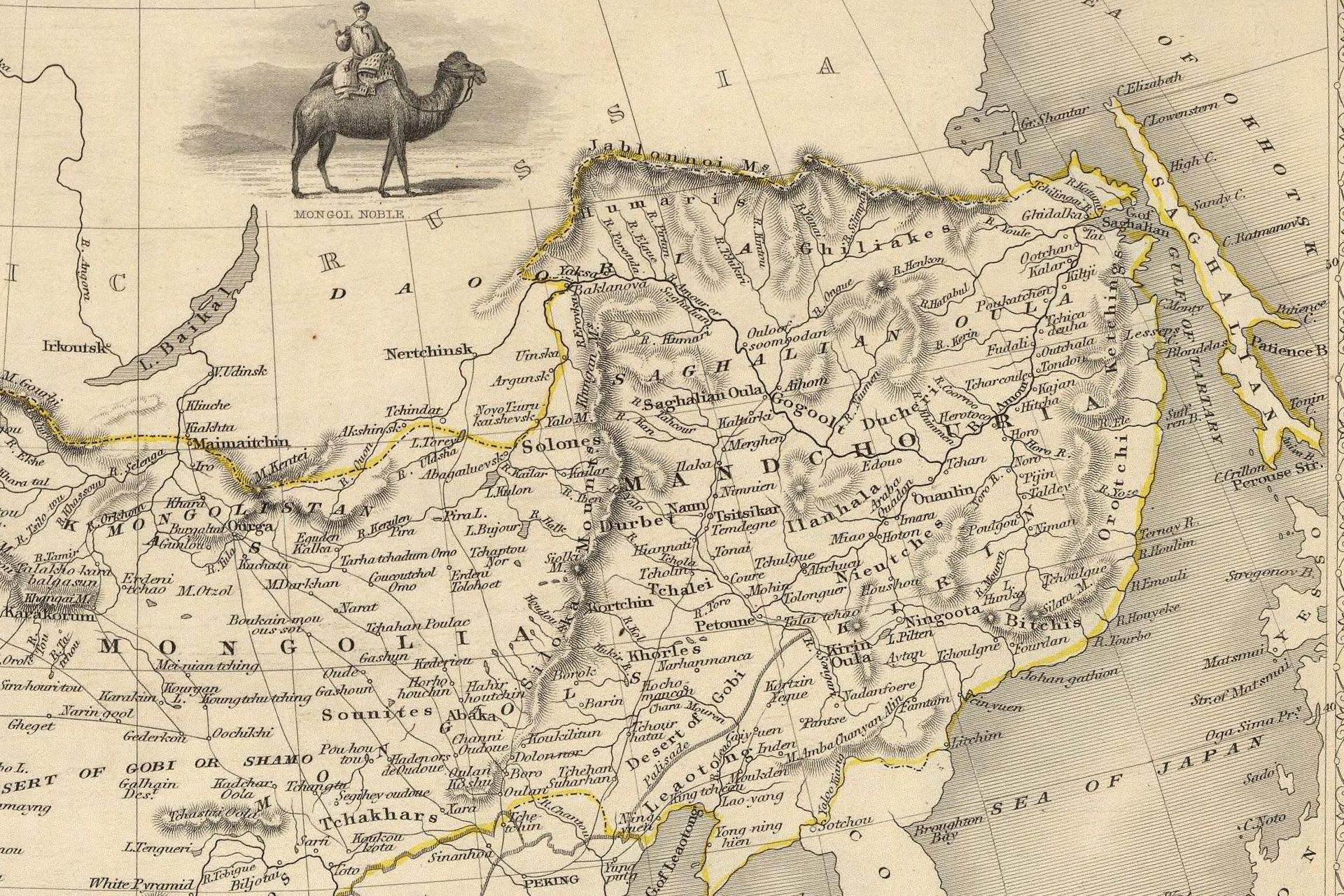

The Russian-Chinese border on a British map from 1851 // uk.m.wikipedia.org

While the empire desperately needed workers, the development of infrastructure in the Far East – the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the port of Vladivostok – made the Chinese the main labor force for heavy work. They also became prominent in gold mining and agriculture. By 1910, the Chinese accounted for 41% of industrial workers in the Amur and Primorye regions.[1]

A distinctive feature of this migration was its “temporary” nature. Thanks to extraterritorial rights, the Chinese did not consider themselves emigrants: legal offenses were not handled by Russian authorities but referred to China.

Military needs also played a role in increasing the Chinese presence. During World War I, Russia mobilized its peasantry, compensating for the labor shortage with migrants. Between 1915 and 1917 alone, over 159,000 Chinese workers were brought to Russia by rail to work in mines, agriculture, and military facilities.

Thus, the appearance of Chinese in the Russian Empire was due to several key factors: geographical proximity and natural wealth, imperial policy that initially encouraged settlement, demographic pressure in Manchuria, the demand for labor in infrastructure and industrial projects, and wartime needs during global conflicts.

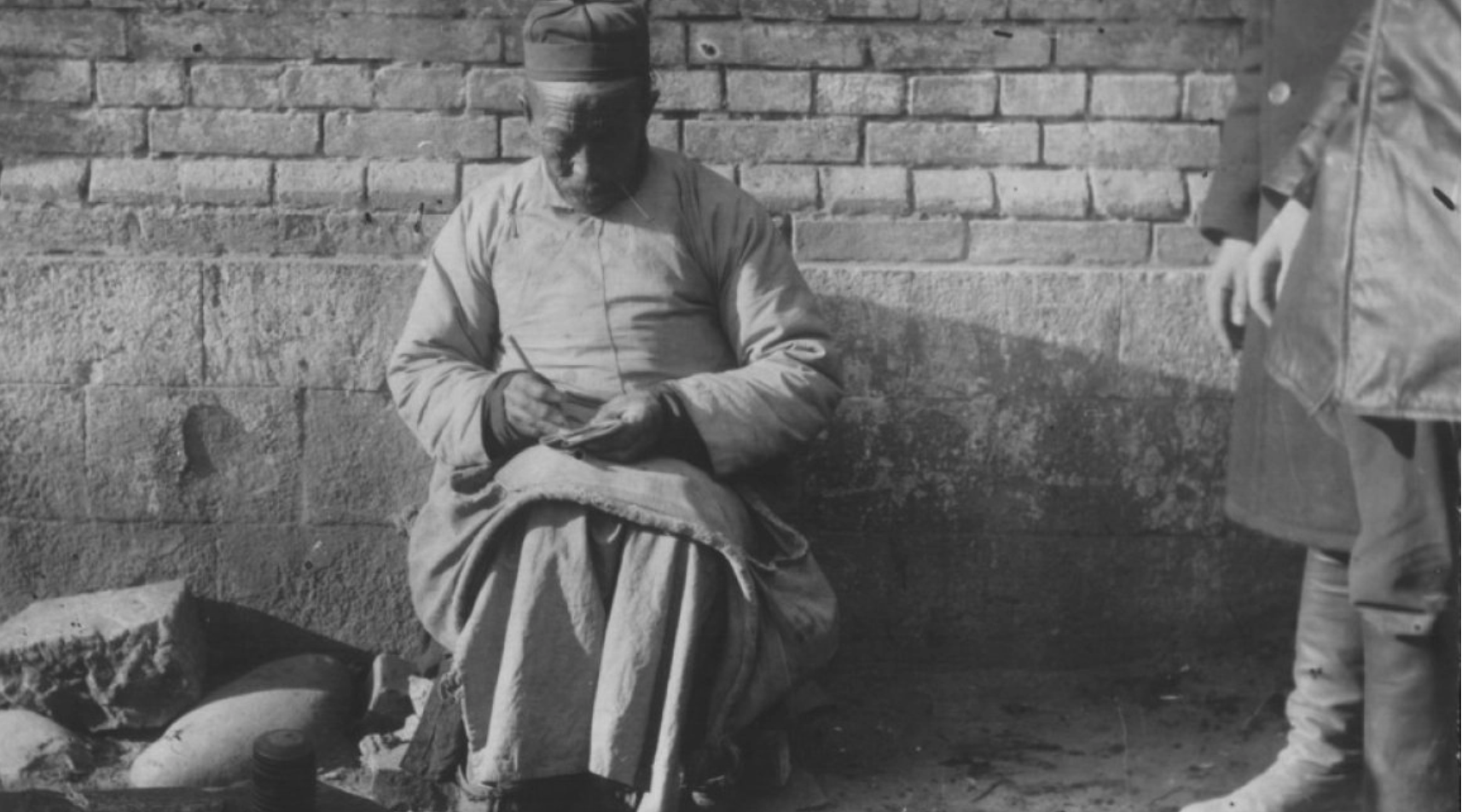

The Merchant in Millionka // www.wilsoncenter.org

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Chinese community numbered in the tens of thousands: in the 1920s, 50–70 thousand people lived in the Primorye region, including 14 thousand in Vladivostok. There, they concentrated in the well-known “Millionka”, a kind of “Chinatown” filled with crowded houses. However, by 1937, the NKVD reported only about 10,000.[2]

Reasons for the Deportations of Chinese

The deportations were driven by a complex set of military-strategic, socio-economic, and foreign policy factors:

-

Border security:

As early as the 1920s, Soviet authorities sought to “cleanse” border areas of foreigners considered potentially dangerous. After Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931, Chinese and Koreans were viewed as “unreliable elements.” Border territories were to be cleared of any potential threats.

-

Temporary migration and weak integration:

Since most Chinese came as seasonal workers, few settled permanently, and even fewer obtained Soviet citizenship. This made the community hard to control and aroused official suspicion.

-

Criminalization of image:

In official press and NKVD reports, the Chinese were often portrayed as sources of trouble: in the 1920s as “hunhuzniks” (bandits) involved in robbery, drugs, and brothels; in the 1930s as participants in smuggling and espionage networks.[3]

-

Accusations of espionage:

During the Great Terror (1937–1938), the Chinese became especially vulnerable. They were mass-arrested and accused of collaborating with Japanese intelligence. As historian Austin Jersild notes, “Soviet ideologists insisted that the Chinese represented an ‘ideological threat’ not integrated into the Soviet propaganda network.”[4]

-

Foreign policy concerns:

The Chinese presence in the Far East also had a geopolitical dimension. Moscow feared that a large Chinese community might serve as a pretext for territorial claims from China.

First Campaigns Against the Chinese (1926–1936)

After the establishment of Soviet power, the “evacuation” of foreigners who had fought in international units of the Red Army and the Cheka began. In February 1921, a special order forced all such individuals – Chinese, Koreans, and others without Soviet citizenship – to leave Soviet territory.

This especially affected Chinese Red Army soldiers and Chekists. While former subjects of the Russian Empire (Latvians, Lithuanians, Finns, Poles) were allowed to remain after the war, the Chinese were denied residence permits or visa renewals, even if married to Russian or Ukrainian women – effectively turning such “encouragement” into deportation.

In April 1921, Fin Fu Rin, a soldier in the Red Army during the civil war, was evacuated by the Cheka from the Donetsk region to Moscow, and from there deported to China. Chin Ho Hai was demobilised at about the same time and sent to Manchuria, where he was immediately arrested. The Chinese in the Cheka were generally not demobilised until 1922. In May 1922, all foreign citizens in Ukraine were forced to re-register, and the number of Chinese in the Cheka fell from about 1,000 to 40–60.[5]

Despite marital and family ties, most Chinese were forced to return home. By the end of that year, the Soviet borders were already under control, and resistance had virtually died out, making the presence of foreign fighters unnecessary.

In the mid-1920s, Millionka in Vladivostok came under repression. Reports and press described it as a dangerous zone linked with crime, smuggling, and espionage.

Between 1926 and 1928, the first mass expulsions of Chinese from border regions took place. Large Chinese households were denied land leases, shops were closed, and entire groups were deported deeper into the USSR. The authorities’ policy aimed to drive the Chinese out of the region – restricting hired migrant labor, closing dens, and deporting smugglers and “spies.”

Thus, between 1926 and 1936, a deliberate “cleansing” of border territories from the Chinese community took place. This policy cemented the image of the Chinese as an “unreliable element” and laid the groundwork for the mass arrests, executions, and deportations of 1937-1938.

The Great Terror: Arrests and Executions (1937–1938)

At the height of the Great Terror, from late 1937 to early 1938, three mass NKVD “operations” were carried out in Vladivostok and surrounding areas. In a ciphered telegram from People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs Nikolai Yezhov, sent on December 22, 1937, to Far Eastern NKVD chief Genrikh Lyushkov, it was explicitly ordered: “All Chinese, regardless of citizenship, who show provocative or terrorist intentions, are to be immediately arrested.”[6]

On the nights of December 29-30, 1937, February 22, and March 28-30, 1938, NKVD officers in Primorye arrested 853, 2,005, and 3,082 people respectively (a total of 5,993 Chinese). [7]

They were subjected to brutal interrogations involving torture and beatings. They were accused of espionage for Japan or China, sabotage, and anti-Soviet activity. In Primorye alone, more than 750 were executed, and hundreds died in prisons. In Chita, 1,500 Chinese were arrested. During interrogations and investigations, one in four Chinese nationals died in Bali alone (117 out of 426), and one in three in Chita (568 out of 1,500).[8]

`According to an “NKVD report on the composition of prisoners as of January 1, 1939,” 3,179 Chinese were held in labor camps.[9]

At the same time, deportations began. In June–July 1938, trains carrying deportees left Vladivostok. Eyewitnesses reported that 7,130 Chinese immigrants and members of mixed families were removed from the Egermsel station. Four of the five trains went to Kazakhstan and further into Xinjiang (China); the fifth carried Chinese who had taken Soviet citizenship – they were sent to Khabarovsk Krai.[10]

Historian Jon K. Chang recorded interviews with relatives and descendants of the deported. One, Wen Xian Liu, born in Shandong province and raised in Vladivostok, worked for Soviet military intelligence. His daughter-in-law, Diliara Abuzarova, recalled: “In 1937, Wen Xian returned from a mission in Manchuria and learned that his wife and stepson had already been deported to Central Asia. He followed them, but the boy died en route. His wife could never forgive him for not being there during the deportation.”[11]

Wen Xian Liu (left)//Chang, Jon K. “East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East.” Eurasia Border Review 9, no. 1 (2018): 56-57

Thus, the deportations and repressions against the Chinese during 1926–1938 became part of the broader Soviet policy toward “unreliable” population groups. A community that had played a significant role in developing the Far East’s economy over decades was almost completely eliminated: some were executed, others deported beyond the region.

Sources and Literature

- Alexeeva, Olga. 2008. “Chinese Migration in the Russian Far East.” China Perspectives, no. 3. https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4033.

- Chernolutskaya, E. N. “The Deportation of the Chinese from Primorye (1938).” Historical Experience of the Discovery, Settlement, and Development of the Amur and Primorye Regions in the 17th–20th Centuries, Vladivostok: Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (FEB RAS), 1993, p. 79.

- Chernolutskaya, E. N. “The Deportation of the Chinese from Primorye (1938).” Historical Experience of the Discovery, Settlement, and Development of the Amur and Primorye Regions in the 17th–20th Centuries, Vladivostok: FEB RAS, 1993, p. 80.

- Jersild, Austin. “Chinese in Peril in Russia: The ‘Millionka’ in Vladivostok, 1930–1936.” Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/chinese-peril-russia-the-millionka-vladivostok-1930-1936

- Chang, Jon K. “East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East.” Eurasia Border Review 9, no. 1 (2018): 47.

- Order from People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs N. I. Yezhov to the Head of the Far Eastern NKVD, G. S. Lyushkov, on the Arrest of Chinese Nationals. December 22, 1937. Alexander N. Yakovlev Foundation Archive. URL: https://www.alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues-doc/1021193

- Chernolutskaya, E. N. “The Deportation of the Chinese from Primorye (1938).” Historical Experience of the Discovery, Settlement, and Development of the Amur and Primorye Regions in the 17th–20th Centuries, Vladivostok: FEB RAS, 1993, p. 80.

- Datsyshen, V. G. “Chinese Labor Migration in Russia: Little-Known Pages of History.” Problems of the Far East, 2008, no. 5: 99–110.

- Report on the Composition of Prisoners Held in NKVD Labor Camps as of January 1, 1939. Alexander N. Yakovlev Foundation. URL: https://www.alexanderyakovlev.org/fond/issues-doc/1009304

- Chernolutskaya, E. N. “The Deportation of the Chinese from Primorye (1938).” Historical Experience of the Discovery, Settlement, and Development of the Amur and Primorye Regions in the 17th–20th Centuries, Vladivostok: FEB RAS, 1993, p. 80.

- Chang, Jon K. “East Asians in Soviet Intelligence and the Chinese-Lenin School of the Russian Far East.” Eurasia Border Review 9, no. 1 (2018): 56–57.