Encyclopedia

Mass deportations from the West of Ukraine in 1939-1940

In 1939, Europe faced the onset of one of the most dramatic events of the 20th century —World War II. This period marked a resurgence of old geopolitical problems, such as the unresolved matters from World War I, under the banner of “Revanchism”. It also saw heightening conflict between totalitarian regimes vying to spread their dominant ideologies — communism and Nazism.

At that time, on the eve of World War II, the lands that make up modern-day Ukraine were split among 4 states — the USSR, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. Each of them had its own sociopolitical system and methods of exerting control over the territories they governed. These states aimed to hold onto Ukrainian lands and annex as much new territory as possible. The western part of Ukraine became a dynamic battleground, shifting between these states and their influence. This struggle led to a tragic toll in human lives, with numerous casualties, mass arrests and deportations.

The people of the west of Ukraine endured significant losses during the German-Polish war, which began on September 1, 1939. With its military might, the German army swiftly advanced through Poland and entered the west of Ukraine by mid-September. Various sources indicate that around 120,000 Ukrainians served in the Polish army in that period. Most of them loyally fulfilled their military obligations, fighting alongside the Poles against the Nazis, leading to the loss of 6,000 Ukrainian lives.

On September 17, 1939, the Red Army crossed the Soviet-Polish border, advancing westward. In just the first few days of the operation, Soviet troops captured the cities of Rivne, Ternopil, Chortkiv, Lutsk, Stanislav, and Halych, reaching the outskirts of Lviv on September, 19. This military campaign resulted in 3,500 Polish soldiers killed, with about 20,000 more wounded or missing [1,17].

The establishment of Soviet government in the west of Ukraine was met with mixed reactions, ranging from outright rejection to cautious support. Some high-ranking officials, senior officers, and political parties demonstrated their disapproval of the communist regime by immigrating to Romania and Hungary. The majority of the local population, however, adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

Some leaders of legal political parties attempted to engage in dialogue with the newly established Soviet government. For example, on September 24, 1939, an 80-year-old elder of Ukrainian politicians in Galicia, Kost Levytsky, led a delegation that expressed readiness to cooperate with Soviet authorities. They requrested permission to continue the activities of Ukrainian economic, cultural, and educational organizations.

In a show of loyalty to the Soviet regime, the leadership of the Ukrainian National Democratic Union (UNDO), the largest Ukrainian political party in the Republic of Poland, decided to cease its activities on September 21. Other legal Ukrainian parties followed suit within days. However, these gestures did not protect them from Stalinist repression, which prioritized the immediate and complete neutralization of all current and potential political opponents. Within weeks in 1939, leaders of the largest legal Ukrainian parties and organizations were arrested and deported to the far east of the USSR.

Even members of the Communist Party of the west of Ukraine soon became disillusioned with the new government. They, alongside with other non-party communists, were targets for mass arrests on suspicion of Trotskyism and other “counterrevolutionary activities” [1,17].

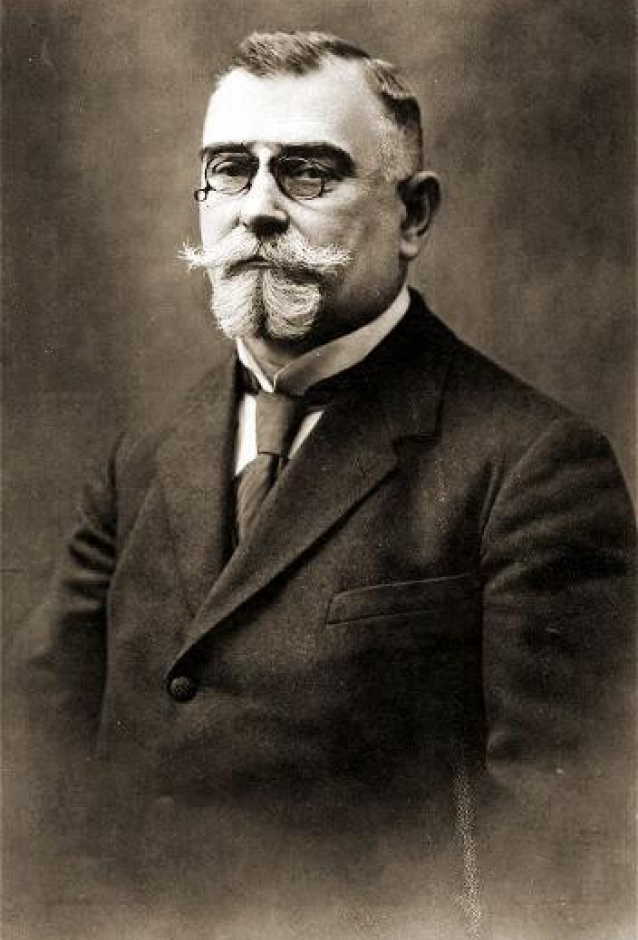

(Kost Levytskyi. Source: https://ridna.ua/2020/11/18-161/)

The Soviet takeover of the west of Ukraine was immediately characterized by mass deportations. Initially, these targeted the leaders of the largest Ukrainian political parties, as well as county and village activists. In late September to early October 1939, The NKVD arrested, deported to Siberia, or killed over 250 individuals. Leading members of Polish and Jewish parties were also detained without charges. The entire staff of the Lviv City Council was arrested, accused of “anti-Soviet nationalist activities.” Many Polish civil society activists were sent to camps for captured officers in Kozel, Ostashkiv, and Starobilsk, where 15,000 were shot in April to May 1940 [2].

![(The family of Polish besiegers Grzegorski from the village of Krykhivtsi, in today's Ivano-Frankivsk region, 1931: Source: https://audiovis.nac.gov.pl/obraz/253760/ [4])](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1940_2.png)

(The family of Polish besiegers Grzegorski from the village of Krykhivtsi, in today’s Ivano-Frankivsk region, 1931: Source: https://audiovis.nac.gov.pl/obraz/253760/ [4])

One of the largest groups forcibly deported by the Soviet authorities in the first wave were ethnic Poles, particularly the “osadniks” — former soldiers who had fought against the Bolsheviks in 1920. On December 17, 1920, the Polish Sejm passed the “On the Granting of Land to Soldiers of the Polish Army” law granting land to soldier of the Polish Army. Those who had distinguished themselves in battle, as well as volunteers who had participated in the fighting, were entitled to receive land free of charge. Others were given land in instalments, to be paid for within 30 years [3]. Many who chose not to farm became policemen, postal or railroad workers, or low-level officials. By 1938, almost 300,000 such Poles resided in Eastern Galicia and Volhynia.

![(Act of ownership of the land of a Polish Osadnik, 1922. Source: https://zn.ua/ukr/HISTORY/operaciya-kolonizaciya-polske-osadnictvo-na-zahidnoukrayinskih-zemlyah-_.html.[3])](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1940_3.png)

(Act of ownership of the land of a Polish Osadnik, 1922. Source: https://zn.ua/ukr/HISTORY/operaciya-kolonizaciya-polske-osadnictvo-na-zahidnoukrayinskih-zemlyah-_.html.[3])

Preparations for the forced eviction of the “osadniks” (besiegers) were detailed in a letter from Lavrentiy Beria to Stalin, dated December 2, 1939, marked as “top secret” and numbered 5332. Beria proposed the arrest of these besiegers, who resided in the occupied territories of the west of Ukraine and Belarus. They were perceived as a threat to the Soviet government since they had received land and material incentives under the Polish government, potentially making them prone to anti-Soviet activities [5].

The letter contained instructions for the NKVD to completely evict the inhabitants of Osadnyk from their homes and transfer them to the Soviet commissariat for timber harvesting, where they would be subjected to forced labour. Beria also directed the development and submission of a plan to the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR for the forced resettlement of the besiegers. This plan was to include details such as a list of property they could take with them, the organization of special settlements where they would be relocated, and the establishment of commandant’s offices at these settlements. Livestock and agricultural tools belonging to the forcibly evicted individuals were seized and handed over to the local authorities [5].

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update

In 1940, according to the archives of the Main Information Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, 17,807 families, or 95,193 people, living in 2,054 settlements in the western regions of Ukraine were slated for deportation. The first stage of deportation, conducted from February 10 to 13, 1940, targeted not only “osadniks”, but also other segments of the population. By February 13, 1940, 17,206 families, or 89,062 people, were deported from the western regions of Ukraine. 1457 people were left behind temporarily due to illnesses; 2152 people were absent during the operation; 34 people had moved to other areas before the operation began [7]. Since not all those marked for deportation under the Soviet plan were evicted, this led to subsequent waves.

The accounts of ethnic Poles who were victims of the deportation vividly demonstrate the process. Mrs. Maria Tarnawska recalls the event: “It was February 10, 1940. My mother was baking bread, and at dawn, two pairs of sledges with drivers arrived: two Ukrainians and two NKVD agents. They announced a sentence (translated into Ukrainian) that we were some kind of enemies and gave us two hours to get ready. But it was winter; we had nothing to wear, and my younger brothers and sisters didn’t even have shoes. They took what we had and put it in feathers and pillows… We were taken to Trembovlia (Ternopil region), loaded into freight cars with bunks, one family on each bunk. There was a hole in the floor that served as a toilet. There were also two iron stoves, and at the stations we were given coal and firewood, water and food, even bread.” [8].

Paragraph 5e of the Directive of March 7, 1940, stated that families were allowed to take luggage weighing no more than 100 kg per family member. However, in most cases, the 100 kg limit was applied to the entire family, not per individual [9].

The second wave of deportations occurred in April and May 1940. According to a decision of the Central Committee of the CP(B)U on March 24, 1940, land ownership limits for families were set for the newly occupied regions of Volyn’, Drohobych, Lviv, Rivne, and Ternopil: 5 hectares in the suburban area, 7 hectares in villages, and 10–15 hectares in mountainous and marshy areas. Since almost a third of the local peasants owned more land than these limits, they were subject to “dekulakization” or eviction. As a result, over 30,000 people were deported to Kazakhstan in April and May. Additionally, residents of the Soviet-German borderland, including the 800-meter border strip and those living near significant military construction, were categorized as deportees.[2]

The third wave of deportations began in the summer of 1940 and targeted relatives of those previously repressed. Merkulov’s directive No. 142, issued of June 4 to all NKVD bodies, stated: “Families of the repressed in prisoner-of-war camps, former officers, police gendarmes, former landowners and factory workers are to be evicted from the western regions of Ukraine and Belarus to the Kustanay and Semipalatinsk regions of the Kazakh SSR for ten years” [7]. The forced eviction commenced on June 29, 1940. According to the summary data of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR of July 2, 1940, 37,532 families, or 83,207 people, including 19,476 unmarried individuals, were deported from six western regions of Ukraine[12, p. 252].

The final, fourth wave of deportations began on the eve of the German-Soviet war, in May 1941. On May 16, 1941, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On the deportation of the enemy element from the Baltic republics, the west of Ukraine and Western Belarus, and Moldavia.” This led to the fourth deportation of the population in June 1941. By June 22, the NKVD had deported 85,716 people, including 12,371 from the western regions of Ukraine. From the fall of 1939 to June 1941, the Soviet authorities occupying the territories of the west of Ukraine repressed and deported 1,173,000 people [1,20].

These criminal forced repressive measures against the western Ukrainian population reveal the tragic scale of the suffering endured by hundreds of thousands of deportees. Expelled from their lands without trial, mainly on political and ethnic grounds, their plight demonstrates the fundamental approach to state governance in the USSR. Even in the newly occupied territories, such as the west of Ukraine, the indigenous population was exterminated or deported if they were deemed inconvenient to the communist regime. Soviet deportations were always extrajudicial in nature [10, p. 432], implemented by imposing collective guilt on entire families, and in part, on entire nations, religious communities, and social classes. This vast scale of deportations led to a violent alteration of the ethnic and sociopolitical composition of the population in the western Ukrainian lands.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Sources & References:

- Сорока Ю. Населення Західної України у 1939–1941 рр.: депортації, заслання, вислання. Етнічна історія народів Європи. Вип.12. Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка, 2001.

- «Задля виконання угоди з Німеччиною». Як СРСР «зачищав» Західну Україну. URL: https://www.5.ua/amp/regiony/na-vykonannia-uhody-z-nimechchynoiu-iak-srsr-zachyshchav-zakhidnu-ukrainu-241810.html

- Операція «Колонізація». Польське осадництво на західноукраїнських землях.URL: https://zn.ua/ukr/HISTORY/operaciya-kolonizaciya-polske-osadnictvo-na-zahidnoukrayinskih-zemlyah-_.html.

- Archiwum fotograficzne Narcyza Witczaka-Witaczyńskiego. Rodzina Grzegorskich Miejsce: Krechowce. URL:https://audiovis.nac.gov.pl/obraz/253760/

- Письмо Л.П. Берии И.В. Сталину с предложением арестовать осадников, находящихся на территории Западной Украины и Западной Белоруссии. Москва 2 декабря 1939 г. // РГАСПИ. Ф. 17. Оп. З.Д. 1016. Л. 115. Рукопись на бланке НКВД.

- История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов: Собрание документов в 7-ми томах. Т. 1. Массовые репрессии в СССР. — М.: РОССПЭН, 2004.

- 80 років тому радянські окупанти депортували мешканців Західної України до Сибіру.URL:https://galinfo.com.ua/news/80_rokiv_tomu_radyanski_okupanty_deportuvaly_meshkantsiv_zahidnoi_ukrainy_do_sybiru_342050.html

- Luty 1940. Deportacja Polaków na Sybir – relacje ofiar. URL: https://dzieje.pl/artykulyhistoryczne/luty-1940-deportacja-polakow-na-sybir-relacje-ofiar

- Łagojda K. Deportacja ludności polskiej w kwietniu 1940 r. w świetle dyrektyw NKWD i relacji wysiedlonych rodzin. Próba analizy porównawczej. URL: http://www.polska1918-89.pl/pdf/deportacja-ludnosci-polskiej-w-kwietniu-1940-r.-w-swietle-dyrektyw-nkw,6543.pdf

- Брандес Д., Зундхауссен Х., Ш. Трёбст Ш. Энциклопедия изгнаний. Депортация, принудительное выселение и этническая чистка в Европе в ХХ веке.[пер.с нем. Л.Ю. Пантиной]. М.:РОССПЭН, 2013.

- По решению Правительства Союза ССР / Сост., авт. введ., коммент. Н.Ф. Бугай, А.М. Гонов.-Нальчик:Изд. центр “Эль-Фа”, 2003.

- Україна-Польща:важкі питання.т.10.Матеріали XI Міжнародного семінару істориків «Українсько-польські відносини під час Другої світової війни». Варшава, 26-28 квітня 2005 року. Варшава, 2006.