Encyclopedia

Peter I’s Forced Resettlement of Kozaks Regiments (1711-1712)

Between 1711 and 1712, Tsar Peter I of Moscow forcefully resettled a portion of the population and Kozaks regiments from Right-Bank Ukraine to the Left Bank. His campaign aimed to dismantle the Kozaks community’s socio-economic base, strengthening imperial control over the region. This process involved the destruction of homes and confiscation of property. Four centuries later, Russia’s deportation of millions from Ukraine’s temporarily occupied territories echoes these imperial tactics, highlighting the continuity of this unaddressed crime. This article explores the factors behind the 1711-1712 Ukrainian Kozak deportations and the methods used by the Russian Empire to suppress them.

The Moscow government’s strategy of forcibly resettling Ukrainians from Right-Bank Ukraine began in 1678-1679, driven by political motives. “Right-Bank Ukraine” at that time spanned the middle sections of the Dniester and Dnieper rivers, covering parts of present-day Kyiv, Cherkasy, Vinnytsia, Odesa, Mykolaiv, and Kirovohrad regions, and northeastern Moldova. The area, densely populated by Kozaks—a military force capable of challenging the Tsar or fostering Ukrainian nationalism—was a concern to Moscow. To counteract this, the Moscow Tsar ordered about 20,000 families from Right-Bank Ukraine to be relocated to the Sloboda region [2]. Alongside the families, Kozak units were also moved across the Dnieper to weaken Hetman Yuri Khmelnytsky’s influence in Right-Bank Ukraine. This extensive relocation of Kozaks is remembered as the “Great Migration.”

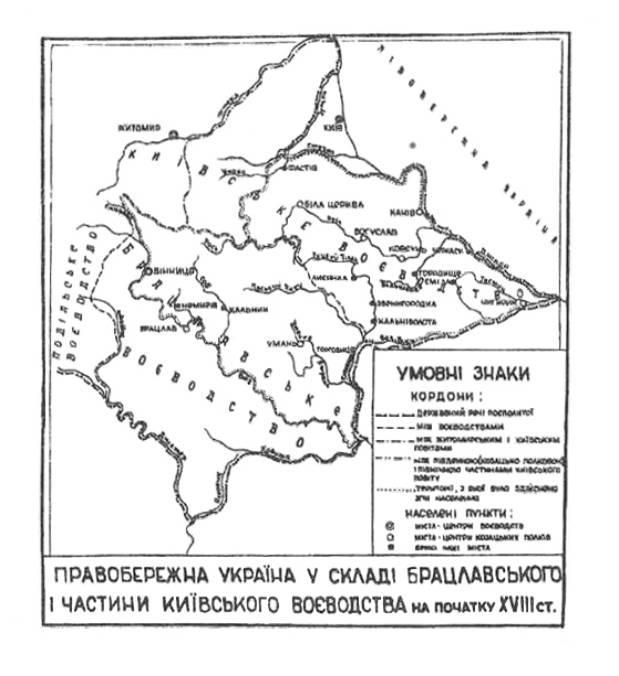

Map of Right-Bank Ukraine at the Start of 18th Century

The 1711-1712 deportation of Ukrainians from Right-Bank Ukraine, orchestrated by Peter I, was part of his larger scheme to centralize power and reinforce control over the empire’s borderlands. This deportation stemmed from various factors:

- Military Strategy: Right-Bank Ukraine was a critical buffer against the Russian Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Ottoman Empire. During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Central and Eastern Europe witnessed numerous conflicts, including the Great Northern War (1700-1721) involving Russia, Sweden, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Ottoman Empire. The strategic significance of Right-Bank Ukraine for defense necessitated tighter control of this frontier.

- Religion: Amidst the Muslim Ottoman Empire and the Catholic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the predominantly Orthodox Right-Bank Ukraine was a “safe world” frontier for the Muscovite state. To avert potential alliances between the Kozaks and enemy states, Peter I resettled them as far from the borders as possible.

- Politics: Right-Bank Ukraine was a hub for anti-Russian sentiment, with its inhabitants seeing Russian influence as a threat to their cultural and political identity. Deportation was a tactic to centralize power and reduce local elite autonomy.

- Economy: The relocation facilitated the development of new regions, exploiting the labor and resources of Right-Bank Ukraine to strengthen the imperial economy. This strategy extended beyond territorial control to economic gain.

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update

The forced displacement of Kozaks and their families from Right-Bank Ukraine also related to political shifts following the 1709 Battle of Poltava. This battle altered the region’s the military-political dynamics, bolstering Russia and weakening Sweden.

Post-Poltava, the Swedish King, Charles XII, took refuge in Bender (Moldavia) and continued plotting against Russia. Right-Bank Ukraine was pivotal in his plans, involving forces led by Hetman Pylyp Orlyk, allied Kozaks, Tatars, and the Polish army.

Pylyp Orlyk, who succeeded Ivan Mazepa as Hetman, emerged as a key political and military leader, gaining widespread support among Ukrainians. In exile, he formed a government, and on April 5, 1710, together with senior military officers, authored “The Treaties and Resolutions of the Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporozhian Army,” often hailed as the first Constitution of Ukraine. This document was a significant step in expressing the Ukrainian people’s political and legal goals.

The concept of independence resonated with segments of the Ukrainian elite and peasantry, offering promises of political and cultural autonomy, and protection from foreign domination.

In 1711, Pylyp Orlyk mobilized an army, heading to Right-Bank Ukraine to reinstate legitimate Kozak governance. His campaign attracted widespread support, including nearly all Right-Bank Kozak regiments. Despite this backing, Orlyk’s bid for an independent state faced challenges: external influences from powers like Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, internal divisions, lack of a unified authority, and limited military resources impeded the unification of Ukrainian lands.

The Russian leadership, reacting to Orlyk’s movements, decided to deport the population from Right-Bank Ukraine to the Left Bank, aiming to undercut his support base.

The fate of Right-Bank Ukraine’s inhabitants hinged on the Treaty of the Pruth (July 12, 1711), which marked Russia’s defeat against Turkey. The treaty required Russia to stop meddling in Poland’s affairs, retreat from its territories, and relinquish claims over the Kozaks, much to Peter I’s discontent, who viewed the local Kozaks as a threat. In response, in September 1711, he decreed the mandatory relocation of Right-Bank Ukraine’s colonels and their regiments to the Left Bank[4].

Reconstruction of Nemyriv Cityscape, Right Bank, from the 16th to Early 18th Centuries

The decree focused on the mandatory displacement of Kozaks, while non-Kozak residents were given the option to relocate voluntarily, a strategy aimed at avoiding public unrest. It also assured resettlers property rights in their new Left Bank homes if they left all their former possessions in Right-Bank Ukraine.

Field Marshal B. Sheremetiev led the operation to displace the Kozaks and the population of Right-Bank Ukraine, with General K.E. Rönne supervising the mission. They commanded a cavalry corps comprising five regiments and additional irregular military units. The eviction operation was initiated in Nemyriv and its vicinity.

General Karl Ewald von Rönne: Head of Resettlement Operations

Under Sheremetiev’s orders, the Nemyriv fortress was demolished, and the local populace, including Kozaks and their families, was transported across the Dnieper. Peasants unwilling to move were allowed to stay, but their food supplies and hay were seized to deter any resistance against the Tsar.

The resettlement initiated in December 1711 is not extensively documented, but its scale was considerable. It’s estimated that over 100,000 people were uprooted from an area of about 35,500 square kilometers, significantly reducing the region’s population [3]. Following the deportation, Russian troops demolished abandoned homesteads and dwellings in Right-Bank Ukraine to deter returnees and seized livestock, grain, and other assets.

Contrary to promises and decrees, the displaced inhabitants from the Right-Bank received no substantial support on the Left Bank, struggling with inadequate housing and lack of resettlement assistance.

Peter І’s actions went beyond deportation. After the Great Northern War, viewing the Kozak army as superfluous and a political threat in Ukraine, he ordered over 20,000 Kozaks to partake in construction projects in the Russian Empire, including building the Fortress of Saint Christ on the Sulak River near the Caspian Sea.

In 1720, construction of the Ladoga Canal commenced, addressing the technical and economic demands of the 18th century. Navigating Lake Ladoga, one of Europe’s largest lakes, was challenging for sailing and rowing vessels, and the transport network of northwestern Muscovy was obsolete.

Despite formidable challenges—a 101-kilometer distance, tough terrain featuring swamps and clay filled with boulders, and a scarcity of stone for bank reinforcement—Peter the Great insisted on rapid completion of the Ladoga Canal.

In 1721, he initiated a massive conscription of Ukrainian Kozaks for the project. Over two years, Hetman Ivan Skoropadsky was forced to dispatch up to 10,000 Kozaks annually, not counting support staff like wagon drivers and cooks.

The Kozaks grappled with strenuous land work from June to September each year. Their task was daunting because of frequent rainfall, flooding the canal, limited food and horse fodder, and inadequate medical facilities. They diverted streams, transported sand, dug ditches, and carried brushwood, planks, and stakes, enduring severe treatment from Russian officers without weekends or holidays. The harsh conditions led to fever and leg swelling among the Kozaks. Hetman Skoropadsky’s pleas for better working conditions were disregarded. In 1721, about 3,000 Kozaks perished during construction, and another 2,500 in 1722 [6].

The Ladoga Canal’s fate was tragic: hastily planned and poorly constructed, it underwent multiple modifications but ultimately deteriorated, becoming unusable by 1826. The forced involvement of Ukrainian Kozaks in its construction represented a severe ordeal and a gross violation of their autonomy within the Hetmanate.

Thus, the 1711-1712 events can be viewed as Muscovite retribution against Ukrainians for supporting Hetman Pylyp Orlyk during the 1711 Pruth River Campaign. The winter deportations, ordered by Peter the Great, affected an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 people. This action severely weakened the Kozaks community, impeding its resurgence and leaving the Right Bank of Ukraine desolate. In the 21st century, Russia mirrors this policy, forcibly deporting populations from Ukraine’s temporarily occupied territories to deprive Ukrainians of their future and their potential for recovery and strength.

Anastasiia Saenko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Sources & References:

- Война с Турцией 1711 года (Прутская операция): Материалы / Изд. А.З.Мышлаевский // Сбор ник военно-исторических материалов. СПб, 1898. Вып.12. Режим доступу: http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/nodes/21405-voyna-s-turtsiey-1711-goda-prutskaya-operatsiya-materialy-izvlechennye-iz-arhivov-spb-1898-sb-voen-ist-materialov-vyp-12#mode/grid/page/352/zoom/1

- Костомаров Н. И. Руина: Гетманства Бруховецкого, Многогрешного и Самойловича. Режим доступу: https://dlib.kiev.ua/items/show/666#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

- Крикун М. Згін населення з Правобережної України

в Лівобережну 1711-1712 років (До питання про політику Петра І стосовно України). Режим доступу: https://web.archive.org/web/20070929092924/http://www.franko.lviv.ua/Subdivisions/um/um1/Statti/2-krykun%20mykola.htm#_edn62 - Письма и бумаги императора Петра Великого. Т. 11, вып. 1 (январь-12 июля 1711). Режим доступу: http://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/316882-pisma-i-bumagi-imperatora-petra-velikogo-t-11-vyp-1-yanvar-12-iyulya-1711#mode/grid/page/162/zoom/1

- Слісаренко О. М. Українське козацтво на будівництві Ладозького каналу. Режим доступу: https://grani.org.ua/index.php/journal/article/view/1239

- Степанчук Ю.С. нищення збройних сил Гетьманщини як елемент системного наступу царського уряду на українську автономію. Режим доступу: http://politics.ellib.org.ua/pages-5131.html