Encyclopedia

The Deportation of Christians from the Crimean Peninsula During Catherine II’s Reign

For years, Russian propaganda has promoted the narrative that the 1778 deportation of Crimea’s Christian population by Russian authorities was for their protection from Muslims. This mirrors how Vladimir Putin currently justifies wars and deportations in former USSR territories, claiming to “protect the rights of Russian speakers,” whom he views as part of the Russian ethnic community. This rationale echoes Catherine II’s actions, who positioned herself as the protector of Christians under Ottoman rule.

The Russian Empire had long aimed to take control of the Crimean Khanate (a state that existed from the 15th to the 18th century on the Crimean Peninsula), crucial for Black Sea basin politics due to its control over the Black Sea, finally succeeding in the 18th century.

Map of the Crimean Khanate. Atlas by Franz Johann von Reilly, f. 61. Vienna, 1789

Thanks to its experienced army and status as an Ottoman Empire vassal, the Crimean Khanate was a formidable opponent. However, from the 17th century, the Russian Empire began to strengthen its positions, notably with firearm advancements, while the khanate lagged in military innovation. Russia’s territorial expansion in Eastern Europe paved the way for conquering the Crimean Khanate.

The 1774 Russo-Turkish War’s conclusion with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca allowed Russia to secure the Northern Azov region (now Southeastern Ukraine and adjacent territories within the Russian Federation). The treaty declared the Crimean Khanate formally independent from the Ottoman Empire, making it more susceptible to Russian conquest.

With the capture of the Azov region, Russia faced the challenge of settling the Wild Fields (the steppe area covering Southeastern Ukraine). Catherine II highlighted the need for settlement, stating, “We need to populate. Make, if possible, our vast deserts swarm with people.” [4] These circumstances led to the deportation of Orthodox inhabitants—Greeks, Armenians, Orthodox and Catholic Ukrainians—by Catherine II, aligning with the Russian Empire’s strategy to strengthen control over conquered regions and assimilate the population. This move, aimed at undermining the Khanate’s economic potential and populating newly annexed lands, marked the peninsula’s first organized deportation.[3]

The Deportation of Christians

The Greek community was dispersed across more than 80 settlements in the mountain ranges and along the southern coast of Crimea, with a quarter of the population residing in cities. Here, they primarily worked in artisanal professions or trade. In Crimea’s rural areas, Greeks engaged in livestock farming and agriculture, cultivating crops like rye, millet, wheat, barley, and flax. On the southern coast, they also developed horticulture, viticulture, vegetable gardening, and fishing extensively. The Khan’s property census, conducted during the deportation, showcased the relative prosperity of most Crimean Greeks and highlighted close economic ties with other ethnic and religious groups—Muslims and Jews [4].

Despite the majority of the Christian population being Orthodox, a myth was propagated to legitimize the deportation, claiming it was to liberate fellow Orthodox Christians from Muslim oppression. However, researchers have identified a completely different reality. Early modern Crimea was characterized by religious tolerance, fostering numerous interfaith marriages and ethnic interactions that enhanced social integration. The peninsula also hosted three higher Orthodox theological schools. Therefore, the narrative of Christians suffering harsh treatment under Muslim rule in Crimea, often cited as justification for their deportation or as a form of “brotherly assistance” from Russia, does not hold true and merely serves as a pretext for political manipulation [4].

The Eviction Process of Crimean Greeks

In May 1778, Russian commander Alexander Suvorov was appointed to oversee all military forces in Crimea and Kuban. He immediately initiated the deportation of the Christian population.

Commander A. Suvorov

The Greeks and Armenians, refusing to leave the peninsula voluntarily, submitted a petition:

“We, the subjects of His Highness (Crimean Khan Şahin Giray), are satisfied with his rule and have been paying tribute to our sovereign from the time of our ancestors; even if they were to cut us with sabers, we do not intend to leave.”

Despite direct threats from Russian emissaries, many opposed the deportation [6]. Christians faced psychological pressure, with rumors spread that the Tatars and Turks intended to kill them [2]. Even then, propaganda was a key tool for the Russian Empire to further its interests.

Crimean researcher Alexander Bertier-Delagarde noted, “Christians left with bitter weeping, ran, hid in forests and caves, and some even converted to Islam, just to remain in their homeland” [4].

The Russian authorities forced Crimean Greeks to abandon their homes, shops, mills, vineyards, and other properties accumulated over lifetimes and through inheritance. The abundance of ownerless property led the Khan to order a detailed inventory.

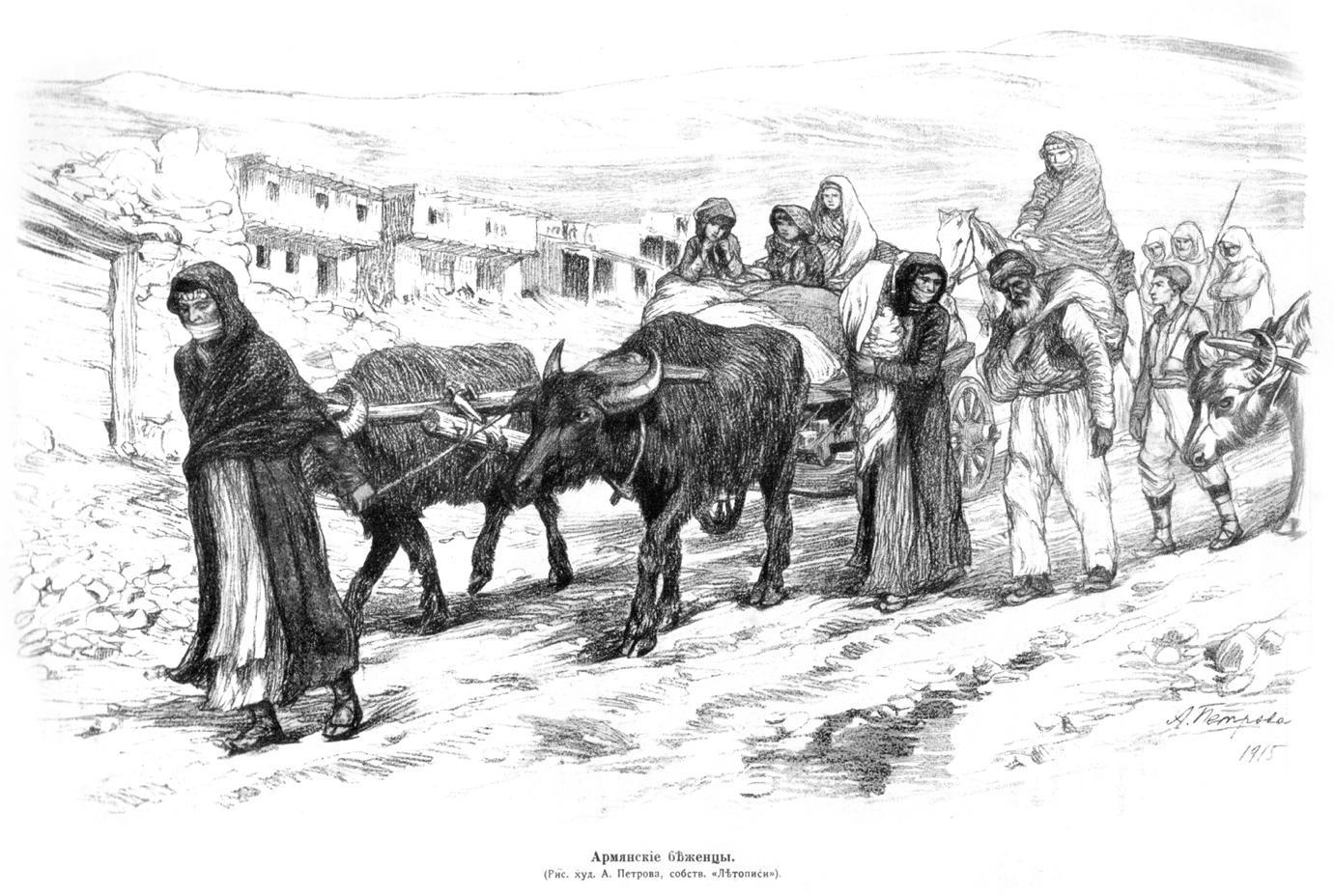

“Armenian refugees”. Drawing by A. Petrov

Near Bakhchisarai, an armed resistance to the deportation was violently quashed by Russian forces. From July 28 to September 18, 1778, under Catherine II’s orders, 30,333 individuals were deported from the Crimean Peninsula, including 15,812 Greeks, 13,316 Armenians, 162 Vlachs, 664 Georgians, and 379 Catholics [7]. As a result, six towns and 60 villages were left deserted, significantly depleting the Crimean Khanate’s economically capable population [3].

“Entire families suffered with their lives, many lost half of their members, and no family was spared the loss of a father, mother, brother, sister, or children; in short, of the 9,000 male descendants, not even a third remained…” – Greek representatives recalled in a letter to St. Petersburg forty years after the deportation [8].

Cities of the Deported

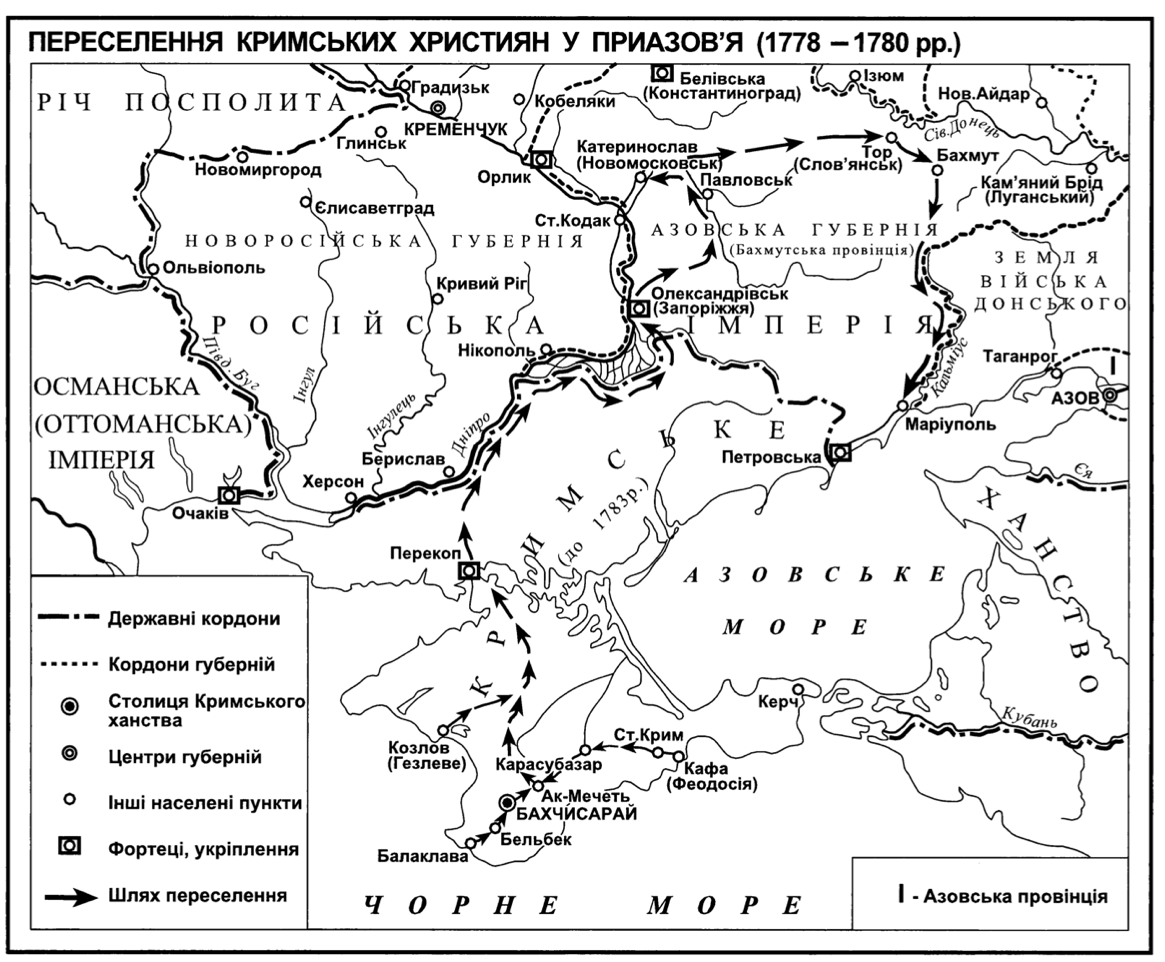

The Christian population from the Crimean Khanate was deported to Novorossiya, within the territories of what are now Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk regions. Novoselytsia, now known as Novomoskovsk in the Dnipropetrovsk region, was initially designated as the central resettlement point for the deportees. However, its distance from the sea and cultural centers rendered it unsuitable for them. The Armenians moved to the Don River’s mouth, founding the city of Nor Nakhichevan, which is now part of Rostov-on-Don. After numerous complaints from the deportees, 18,000 Greeks from Crimea were allowed to relocate to the Sea of Azov’s shores, where the climate and agricultural conditions were more favorable. There, they established the city of Mariupol on the site of an ancient fortress.

Resettlement of Crimean Christians to the Azov region

Mariupol

In the Mariupol district, each family was allocated 30 desiatynas of land, along with seeds for sowing. The local residents were exempted from taxes and military service in the Russian Empire, and legal issues were to be adjudicated in a local Greek court [5]. Despite these provisions, by 1781, three years after deportation, the Greek population in Mariupol had decreased to 14,483, nearly 4,000 fewer than at the time of resettlement. Attempts by the Greeks to return to Crimea were forcefully thwarted by the Russian Empire, which banned their return to historical lands and dispatched military units to enforce the prohibition.

Two centuries later, in 2022, Russian forces occupied and devastated the city of Mariupol. Recent reports indicate that about 45,000 residents, including ethnic Greeks and Armenians, were deported [1].

Exhibits from the Sartana Local History Museum, brought by villagers from Crimea. Source: https://localhistory.org.ua/texts/reportazhi/mariupol-tse-ukrayina/

The July to September 1778 deportation of Crimean Christians reflects the colonial policy of the Russian Empire under Catherine II’s rule. The completion of this process and the formal annexation of the Crimean Khanate by the Russian Empire in 1783, aiming for control over and dominance of the Black Sea, highlights Russia’s long-standing imperialistic ambitions, indifferent to the devastation of countless lives. Despite efforts, Crimean Greeks and Armenians were largely prevented from returning to their homeland. In the 21st century, mirroring the 18th century, Russian authorities persist in employing imperial tactics such as terror, intimidation, and deportations. Russia’s ongoing actions in Ukraine indicate the continuation of these methods, which belong to a bygone era.

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Sources & References:

- Бака В. Чому депортація маріупольців – це повторення історії?. Режим доступу: https://uinp.gov.ua/informaciyni-materialy/rosiysko-ukrayinska-viyna-istorychnyy-kontekst/chomu-deportaciya-mariupolciv-ce-povtorennya-istoriyi

- Гедьо А. Переселення греків з Криму до Північного Надазов’я у 1778 р. (Аналіз джерел). Режим доступу: https://elibrary.kubg.edu.ua/id/eprint/29962/2/ΑΓΓΕΛΛΙΑΘΟΡΟΣ.Вісник%20.pdf

- Громенко С. Як Росія будувала Маріуполь на сльозах і крові. Режим допису: https://uifuture.org/publications/yak-rosiya-buduvala-mariupol-na-slozah-i-krovi/

- Джувага В. Одна з перших депортацій імперії. Як кримськими греками заселили Дике Поле. Режим доступу: https://www.istpravda.com.ua/articles/2011/02/17/25350/

- Драпак М. Маріуполь та греки: зберегти свій дім. Режим доступу: https://localhistory.org.ua/texts/reportazhi/mariupol-tse-ukrayina/

- Короленко Б. Алєксандр Суворов. Примара імперії. Режим доступу: https://tyzhden.ua/alieksandr-suvorov-prymara-imperii/

- Кримські депортації: від Єкатерини ІІ До Сталіна. Режим доступу: https://old.uinp.gov.ua/news/krimski-deportatsii-vid-ekaterini-ii-do-stalina

- Мариуполь и его окрестности.Мариуполь.1892. Режим доступу: https://uk.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Файл:Мариуполь_и_его_окрестности._Отчет_об_учебных_экскурсиях_Мариупольськой_Александровской_Гимназии.pdf&page=18