Encyclopedia

Victims’ Testimonies of the Soviet Forcible Deportations

The mass deportations orchestrated by the Soviet Union led to both a demographic crisis and a national tragedy in the temporarily occupied countries of Ukraine, the Baltic States, and Poland. These deportations spanned from the 1920s to the 1950s and targeted various ethnic and social groups, but they all had a common thread: they were tools of Soviet governance.

To justify these human rights abuses, communist punitive authorities often cited different reasons. One of them was an ethnic factor, as in the case of ethnic Germans, who were accused of supporting fascism and then forcibly evicted from Ukraine. This dramatically altered the ethnic makeup of the Bessarabia region and many settlements in Volyn, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia regions, where German communities were wiped out. Official figures show that the German population in Ukraine plummeted from over 390,000 to just 38,000 people in the first half of the 20th century [1]. Similarly, ethnic Poles (Polish siege victims) living in the West of Ukraine were deported due to alleged connections with the Polish army’s anti-Bolshevik efforts in 1920.

Another rationale for forced deportations from Soviet-occupied territories was socio-political. People belonging to specific social groups — such as intellectuals, wealthy villagers, clergy, or members of national-patriotic movements — were sent to distant parts of the USSR like Siberia and the Far East, often with no chance to return.

Estimates suggest that around 6 million people in Ukraine, the Baltics, and Poland were targeted by Soviet deportations [2]. But these staggering numbers represent individual human lives, as well as tragedies of families and entire nations. In this article, we’ll share first-hand accounts from those who endured these devastating deportations.

In the 1930s, the Soviet government initiated a policy of dekulakization, marking the start of a series of deportations in Ukraine. This policy targeted wealthy peasants, forcing them from their homes and relocating them to distant regions of the USSR.

Vira Baran, born in 1928, recalls the struggles of her family during this period: “My father was deported to the Far East in 1933, my grandmother and my aunt’s family were sent to the Urals. They were thrown out of their home and, together with two other families, they — a mother, two daughters, a grandmother and her sister — had to huddle in a stranger’s house on a farm in the Urals. The father of that family was also labeled as a kulak and taken away, leaving his family to disavow him to remain in their house” [3].

Ivan Diachok, from the vilage of Petevchytsi in the Lviv region, recalls the impact of dekulakization in the West of Ukraine between 1939 and 1940: “Repressions affected our village as well. Some families were deported… The wealthy villagers were dekulakized and their families were deported. In the neighboring village of Seredpiltsi, the entire tik (a place for grinding and drying grain) of wealthy villagers was burned, and every family member was expelled to Siberia” [4].

Dekulakisation of a peasant P. Masyuk. Udachne village, Donetsk region. 1934.

Photo from the funds: Central State Film and Photo Archive of Ukraine named after H.S. Pshenychnyy [5].

As noted above, the Soviet authorities’ repressive actions extended beyond Ukrainians to include ethnic Poles, Germans, and other groups. Maria Tarnawska, an ethnic Pole, recalls the deportation from the West of Ukraine: “It was February 10, 1940. My mother baked bread, and at dawn two pairs of sledges with drivers arrived: two Ukrainians and two NKVDists. At first, they announced the verdict (translated into Ukrainian) that we were some kind of enemies and gave us two hours to prepare. But it was winter, we had nothing to wear, and my younger brothers and sisters didn’t even have shoes, so they took what we had and put it in feathers and pillows… We were taken to Trembovlia (Ternopil region), loaded into freight cars with bunks, one family per bunk. There was a hole in the floor that served as a toilet. There were also two cast-iron stoves, and at the stops we were given coal and firewood, water and food, even bread” [6].

Yevheniia Smolnytska and her family were also deported from the West of Ukraine. She recalls: “Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, on 10 February 1940, at night, NKVD officers and Russian soldiers entered our house. They gave us an hour to pack and loaded us onto a sled. Along the way, they stopped the sled near the house of the second owner of the grove who lived nearby, and together they took us to the railway station in Baranovychy. There were trains at the station, and there were already many people in the carriages. The doors of the carriages were still open. My mother heard her younger sister’s voice and ran to the carriage, but a soldier closed the door. She never saw her sister again” [6].

“That year’s winter was harsh,” recounted Alfreda Ferschke in her testimony. “Thirty-degree frosts gripped this troubled land, and the night of February 10, 1940, left a mark on my psyche and personality for life… The morning was already cold, with the snow creaking in the dead silence. No one spoke: even the guards remained silent. That night, sledges, and cars arrived to transport all the military prisoners from the Podryże colony and other colonies in Volyn. Along the way, a woman offered us a cup of hot milk — the last we could have for a break of six years…

Under escort, we were loaded into wagons already filled with strangers. Plank bunks lined on both sides of the carriage. An iron stove with a pipe stood in the middle. A hole in the floor served as a toilet. The carriage featured two windows on each side. We were assigned seats upstairs, where other families had already settled. The space was cramped, dark, and cold. Facing such a grim reality was terrifying: I feared the darkness and everything around me…

After the carriage was loaded, we heard the creak of the sliding door as it was secured with an iron rod and locked. The train moved so fast that some of us were thrown from our beds. The rhythmic knocking of the wagon wheels filled the dark space, accompanied by a chant: ‘Dear mother, defender of people.’ Everyone joined in, their voice mingling with cries. Our parents held us tightly, crying along. No one knew our destination, but they assumed it was Siberia [6].”

Deported Polish children in Siberia, 1940. Alfreda Ferschke is marked in the circle.

Photo from the Alfreda Ferschke archive.[6].

Remarkably, the Soviet communist authorities persisted with deportations even amidst the active hostilities of the Soviet-German war. Ethnic Germans residing in the Soviet Union bore the brunt of this policy. In July and August 1941, they were mass-accused of aiding the Nazis and forcibly deported to Siberia and Central Asia. Here are some preserved accounts from that period spanning 1941 to 1946:

Vira Kovaleva (Strom), the daughter of one of the deportees, recalls: “Deportations were already underway in Crimea. On that day, my mother’s family left Kurman-Kemelcha (now known as Krasnogvardeiske) in a one-and-a-half (Soviet car), joining hundreds of other Germans. Initially, they were sent to Transcaucasia, to the region then known as Ordzhonikidze Krai (now Stavropol Krai, Russia). After residing there for a period, they were relocated to Northern Kazakhstan in November 1941” [7].

Ewald Schultz, born in 1937 and of German ethnicity, recalls his family’s deportation from the Kharkiv region to the Prisnogorsk district in the Kustanay oblast of the Kazakh SSR in 1942. “My father came home from work from his shift. He worked as a carpenter… He approached my cradle and looked at me. Most likely, he already knew something. As my mother said, he shed a few tears before holding me in his arms. Shortly after, a ‘voronok’ (a vehicle used by the USSR security forces) arrived to take him away. As a matter of fact, I don’t remember him, nor do I have a single photo of him” [7].

Elvira Pleska (Zebold), the daughter of a repressed man, told her story: “They took the whole family unexpectedly. They gave us very little time to pack. Even after deportation, in general, Germans were often employed in hazardous industries. Despite my parents’ hard work, they were treated terribly, labeled as enemies of the people, and they ate very poorly.”

One of the wagons in which deported Germans living in the USSR were transported.

Photo source: NV New Voice [8].

Despite the substantial demographic losses sustained during World War II and its aftermath, the Soviet regime persisted with mass deportations. Following their reoccupation of the West of Ukraine, they initiated Operation “West” in 1947, resulting in the deportation of approximately 78,000 individuals accused of backing the Ukrainian national resistance [9].

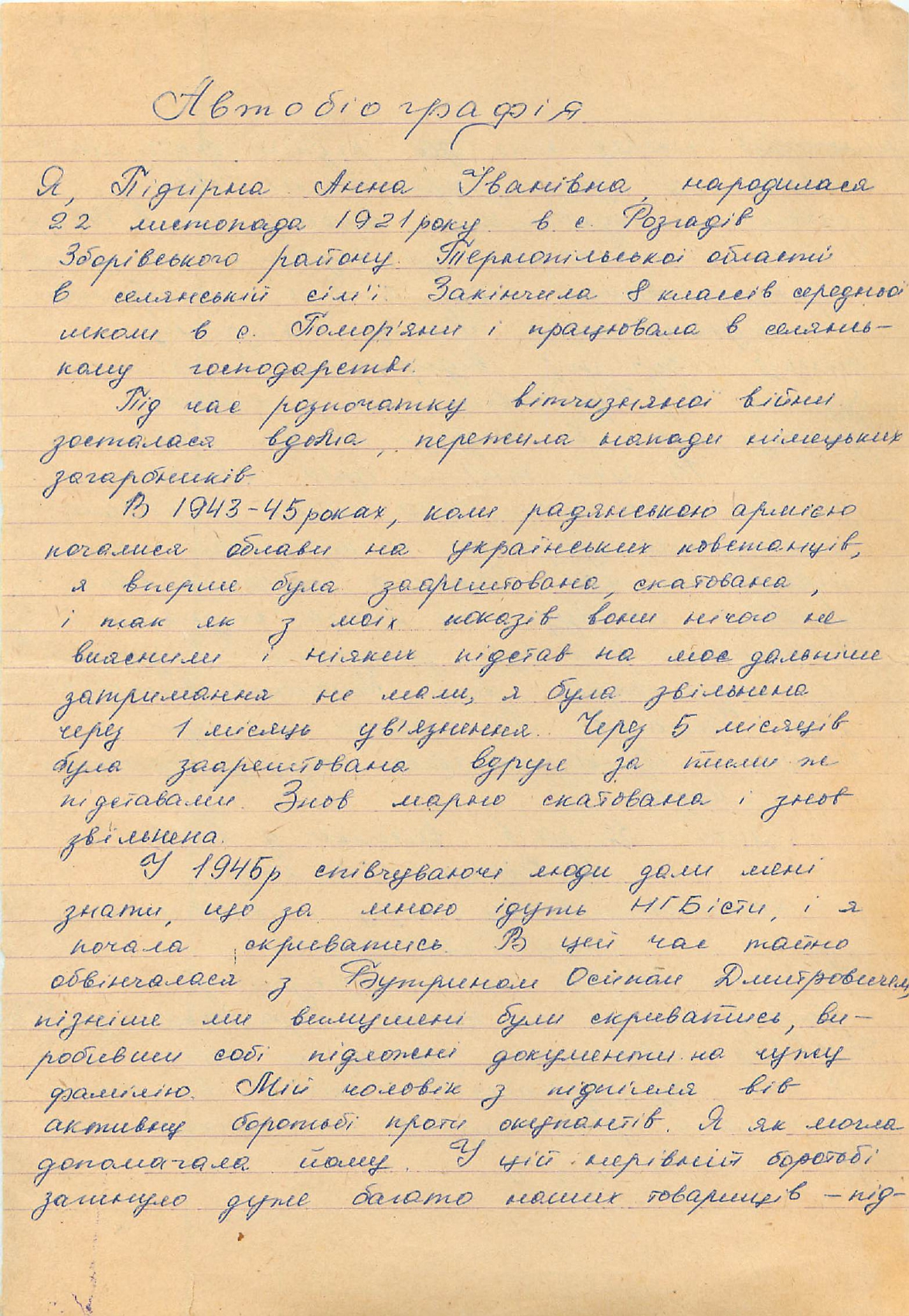

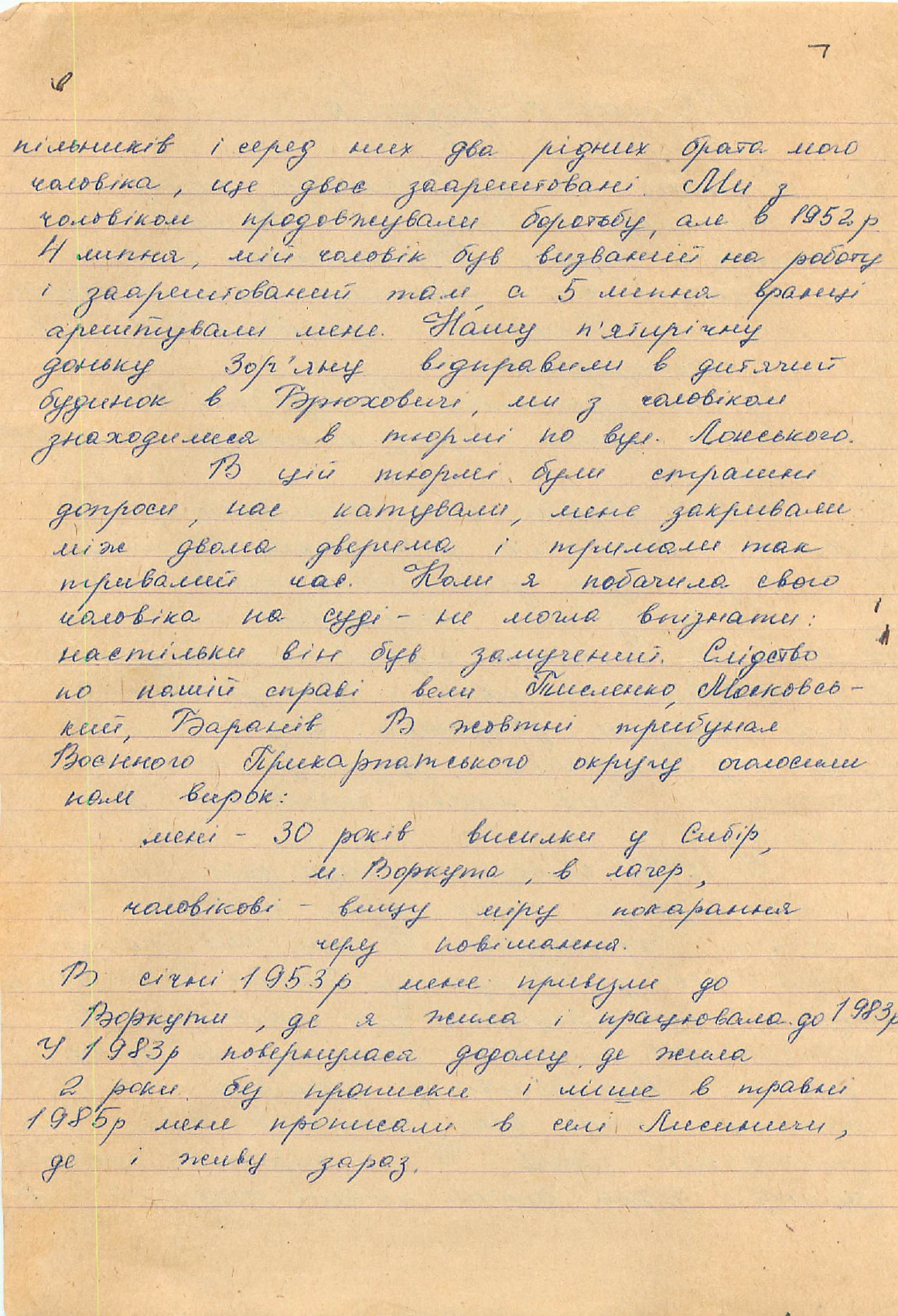

Anna Pidhirna recounted her traumatic experiences: “In 1945, individuals who sympathized with me warned that the NGB was pursuing me, prompting me to go into hiding. During this period, I secretly married Osyp Butryn, and we later assumed false identities to maintain our cover. My husband actively resisted the occupiers through underground movements. I supported him as much as I could… Two of my husband’s brothers died in this unequal fight against the Soviets… My husband and I continued to resist until, on July 4, 1952, when my husband was arrested, followed by my arrest the next day. Our five-year-old daughter, Zoryana, was placed in an orphanage in Bryukhovychi while we were incarcerated on Lonskoho Street… There we were tortured and abused… In October, the Prykarpattia Military District tribunal announced our sentences: 30 years of exile in a Vorkuta camp in Siberia for me, and death by hanging for my husband [10].”

The post-war period saw a surge in mass deportations orchestrated by the Soviet regime, affecting the Baltic States — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — as well. One notable operation was “Priboi” in 1949, during which 94,779 individiuals were forcibly removed from their homes [11].

Tiina Margus (Liias) recalls: “1949 was the most terrible year. I remember my father was in the city before the deportation. He was declared a kulak… When he returned from the city, he was asked not to come home for a few days because he might be deported… That night he did not come home, and meanwhile, armed men came to our yard. When my father returned, they gave us half an hour to get ready, put us on a cart and took us away. Then we were put on the train. My father was looking out the window of the carriage, thinking that maybe we were going to Kohtla-Järve (a city in northeastern Estonia) or somewhere else. And suddenly, he told the children that we were deported to Siberia… [12]”.

Dzydra Mejdere, born in 1928 in Latvia, became a member of the Latvian partisan movement alongside her husband, Laimonis Lapa, in 1945. Laimonis was killed on March 11, 1949, and Dzydra was arrested and shot in the right arm. She was detained in the NKVD building in Riga, known as the Corner House (Stūra māja) [13].

Dzydra vividly described the brutal treatment she endured during her imprisonment: “My interrogator was Migla, but he had assistants who were ‘tireless’ and ‘really wonderful’. No wonder they were given flowers in Soviet times. These monsters… One would come, finish, and another would come. For a person who did not see what was happening, who did not experience it, who does not know it, it seems simple — what you were asked, you answered, and what you do not want to answer, you can keep silent. No, it was not like that. For them, you were a nobody with whom they could do whatever they wanted. They threatened and tortured you. It was not easy. They used to beat me. I feel sick just thinking about it… [14]”.

Reflecting on the personal accounts of those who suffered under Soviet deportations, a consistent narrative emerges: the communist repressive machine sought to forcibly evict millions of people, fabrication various justification for their actions. A review of the sheer number of victims, the widespread geographical locations, and the diverse backgrounds of those targeted leads to an inescapable conclusion. The USSR was intent on eliminating anyone unwilling to conform to its totalitarian dictatorship.

It is a grim chapter in history, one that echoes ominously today as Russia engages in the forced deportation of Ukrainians from the temporarily occupied territories of sovereign Ukraine.

It is a cycle of cruelty that must not be repeated.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Documents:

1. Anna Pidhirna autobiography with information about her deportation to Vorkuta in 1921-1985 [10],p.1.

2. Anna Pidhirna autobiography with information about her deportation to Vorkuta in 1921-1985 [10], p.2.

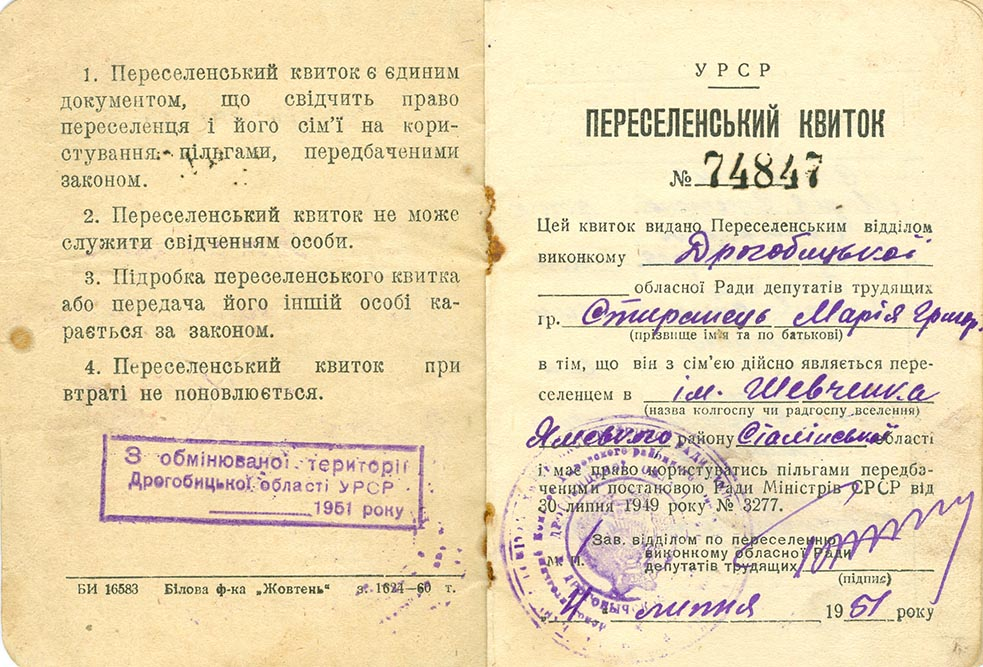

Resettlement card of M.H. Styranets. 1951, who was evicted from the Drohobych region to the Stalin region of the Ukrainian SSR. (From the family archive of Mariia Lesyk (Stryranets)) [15].

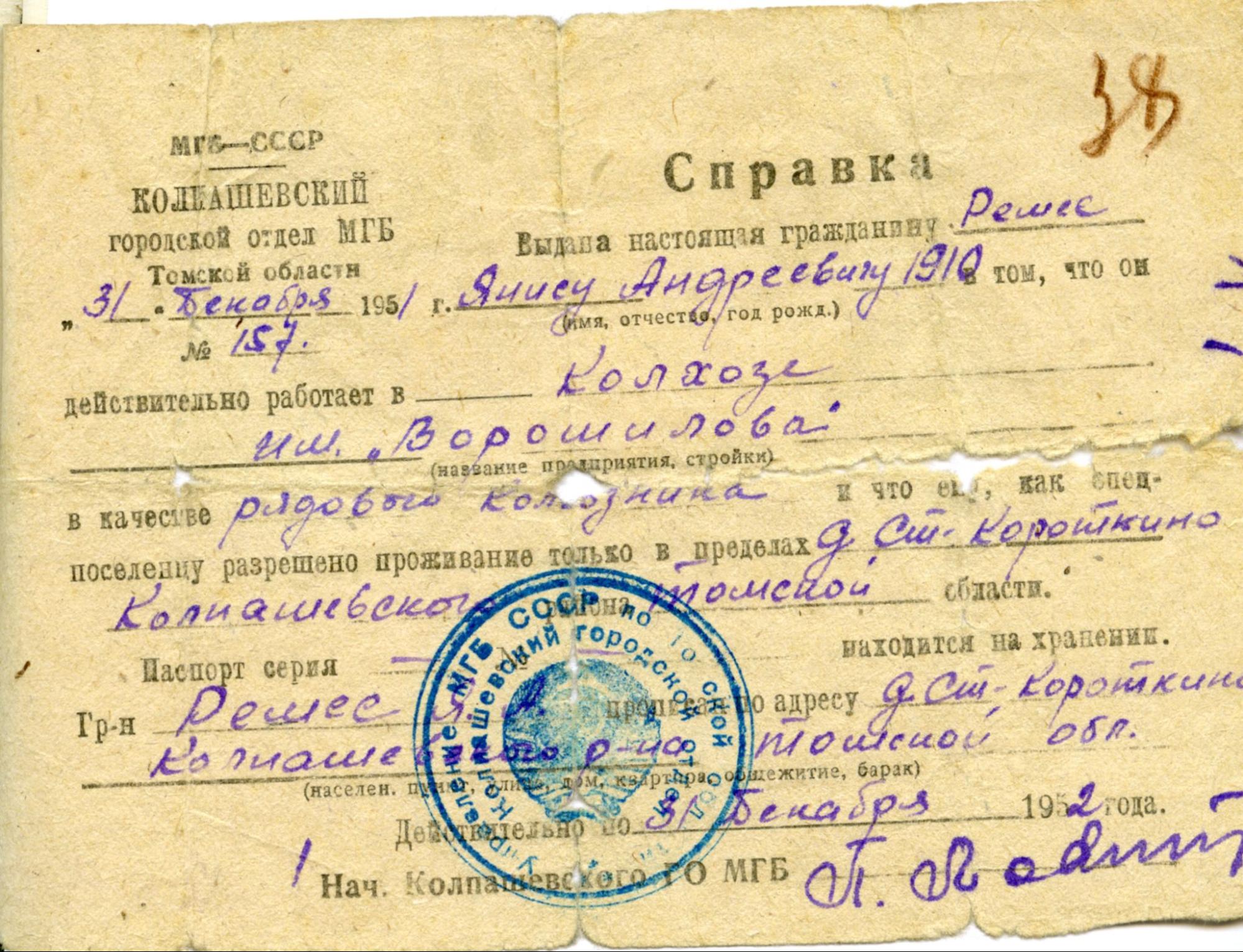

A document issued to deported Latvian citizen Janis Remis, confirming his employment as a collective farm worker in the Tomsk region, Siberia, RSFSR.

Source: The funds of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.

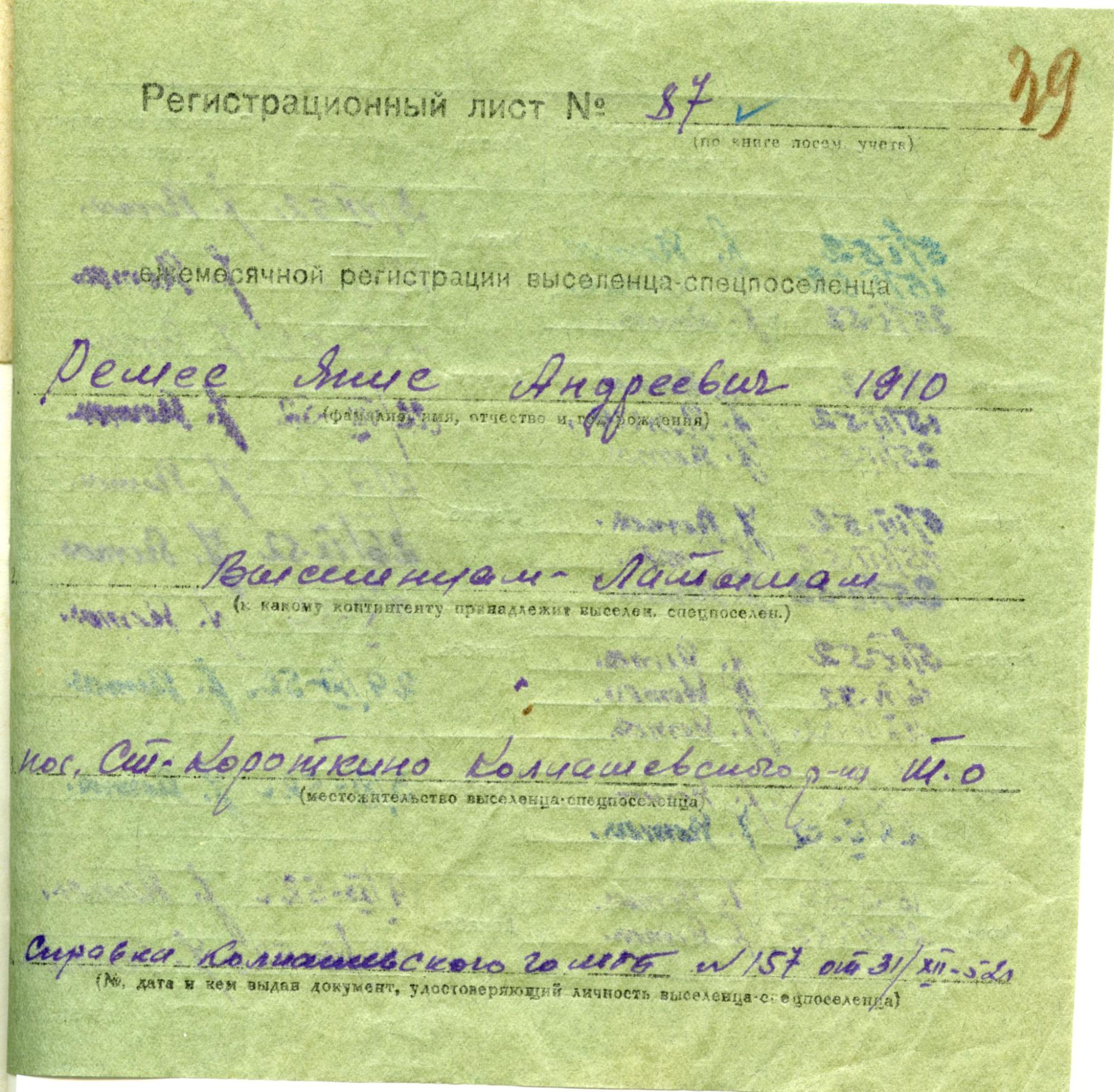

Registration card of forcibly deported Latvian citizen Janis Remis, a special settler in the Tomsk region, Siberia, RSFSR.

Source: The funds of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.

Sourses & References:

- Forcible Deportations of the Ukrainian Germans in 1935-1941 URL:https://deportation.org.ua/forcible-deportations-of-the-ukrainian-germans-in-1935-1941/

- Павел Полян. Любимые игрушки диктатора. Размышления о советской депортационной политике URL: http://index.org.ru/journal/14/polyan1401.html

- Розкуркулення на Поліссі – «землю забрали по самі двері хати». Дві історії з півночі та з півдня України. URL:https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/rozkurkulennia-svidchennia/30959015.html

- Інтерв’ю з жителем с.Петевчиці Дячком Іваном Григоровичем про радянську окупацію Західної України 1939-1941 років. Електронний архів українського визвольного руху. URL: http://avr.org.ua/viewDoc/24005

- Петренко І. Голодомор на фото Марка Залізняка URL:https://localhistory.org.ua/rubrics/photo/golodomor-na-foto-marka-zalizniaka/

- Luty 1940. Deportacja Polaków na Sybir – relacje ofiar. URL:https://dzieje.pl/artykulyhistoryczne/luty-1940-deportacja-polakow-na-sybir-relacje-ofiar

- Депортовані. UA version URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1H2X8lRu2U

- Максим Бутченко. Депортація з ознаками геноциду. Як у 1941 році Сталін примусово вивіз 100 тис. українських німців з їх рідних земель. URL:https://nv.ua/ukr/ukraine/events/deportaciya-nimciv-z-ukrajini-i-stalinski-chistki-1930-40-h-istoriya-ukrajini-50105422.html

- Примаченко Я. Операція “Захід”. URL: https://www.jnsm.com.ua/h/1021Q/

- Автобіографія Підгірної Анни із відомостями про депортацію в Воркуту за 1921-1985 роки. Електронний архів українського визвольного руху. URL:http://avr.org.ua/viewDoc/24036

- Mertelsmann, Olaf; Rahi-Tamm, Aigi. Soviet mass violence in Estonia revisited // Journal of Genocide Research. Volume 11, 2009 – Issue 2-3: New Perspectives on Soviet Mass Violence.

- Интервью с Tiina Margus (Liias) о депортации отца и его детей в Сибирь в 1949 г. Sourse: Kogu Me Lugu Oral History Portal. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xa6EKFgEuDM

- Гулаг онлайн. Свидетели депортаций в странах Балтии. Дзидра Мелдере. URL: https://gulag.online/people/dzidra-meldere?locale=ru

- Дзидра Мелдере – Меня пытали на допросе. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5ShMytS24c.

- Доля родини – доля переселенців України. Музейні колекції Національного музею історії України у Другій світовій війні. URL: https://collections.warmuseum.kyiv.ua/theme/Warmus/pages/dolya/

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update