Deportations from the Baltic Countries in 1940-1941

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

Encyclopedia

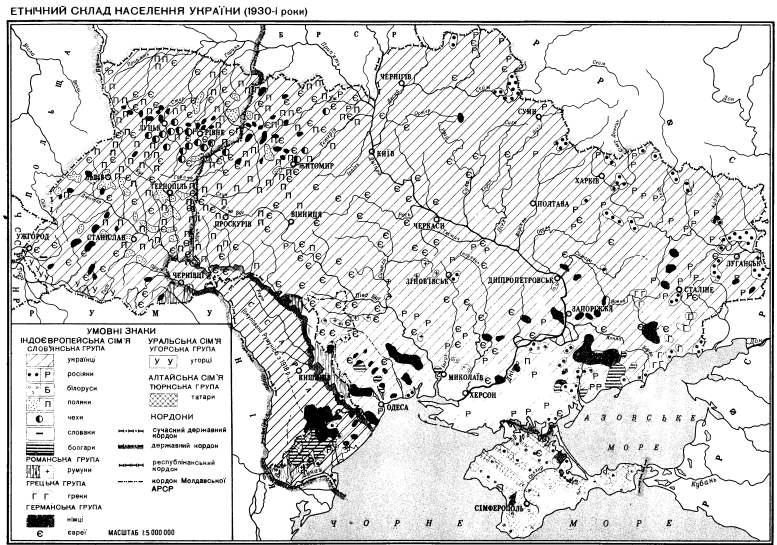

Before the Soviet occupation, Ukraine was home to a diverse population, including Greeks, Turks, Germans, Poles, Jews, Armenians, and other ethnic groups. The Bolshevik ideology aimed to cultivate a “pure Soviet man,” effectively eradicating this diversity. While the Soviet authorities concocted different justifications for the removal of each ethnic group from Ukrainian territory, the method remained consistent: forcible deportation. This article focuses on the forced removal of ethnic Germans from Ukraine.

To understand this event fully, we must first explore the historical presence of Germans in Ukraine. There were two significant waves of migration to the region. The first wave occurred during the periods of the Kyivan Rus’ and the Galicia-Volhynia principality (10th–12th centuries), when Germans were drawn to the rich and fertile lands of Ukraine. They generally integrated with other ethnic groups already residing there, occasionally establishing new settlements. However, the initial wave of migration was smaller compared to the second wave, which began in the late 18th century amid the partitioning of modern Ukraine between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. [1, с. 112].

On December 4, 1762, Russia Empress Catherine II issued a declaration inviting the rural populations of European countries to relocate to the Russian Empire, primarily to settle in the newly colonized territories of Ukraine. This invitation was accepted by many Germans who were seeking refuge from the wars between German principalities at the time. The first group of these migrants established eight colonies: Khortytsia, Khortytsia Island, Neuendorf, Rosenthal, Einlage, Neuburg, Kroneweide, and Schönhorst. Additionally, Germans settled in the provinces of Kherson and Tavriya, as well as Volyn, Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv regions. Consequently, the first census in the Russian Empire in 1897 recorded a population of 377.8 thousand Germans residing in the aforementioned areas of what is now Ukraine [2, p. 88].

By 1923, the Odesa province alone was home to 206 German farms, colonies, and villages. Other provinces also had substantial German populations, with 162 in Dnipro, 147 in the Donetsk, and 143 in Volyn. Moreover, there were several dozen village councils, each comprising 3–5 settlements, that had a predominantly German population. The 1926 census provided more detailed data, revealing that 393.9 thousand Germans (constituting 1.36% of Ukraine’s population) were living in Ukraine at that time. A significant majority of this demographic, over 360 thousand individuals(or 93.2% of the German population in Ukraine), resided in rural areas. Notably, Ukraine was home to 40% of the entire German population in the USSR during the period [2, p. 91].

According to the 1939 census, approximately 392,458 individuals of German nationality resided in the Ukrainian SSR, distributed as follows: around 91,500 people in the Odesa region, 89,400 people in the Mykolaiv region, 89,400 people in the Zaporizhzhia region, and 51,300 people in Crimea [6].

The forcible deportations of Germans commenced in the early years of the World War II. However, anti-German campaigns orchestrated by the Soviet authorities had been underway long before, with the initial ones tracing back to the 1920s. During this period, German engineers and specialists were invited to the Soviet Union to work in industrial facilities and contribute to the forthcoming industrialization, facilitated by the burgeoning German-Soviet trade and economic relations. Contrarily, the Soviet security forces and political leadership perceived them, along with the entire German population in the USSR, as potential German intelligence agents and anti-Soviet activists.

This sentiment was officially articulated in the circular letter No. 7/37 of the OGPU of the USSR “On German Intelligence and the Fight Against It” (July 9, 1924). It stated: “After the conclusion of the Treaty of Rappal, the German industry and trade were provided with the opportunity to expand their activities on the territory of our republic. From that moment on, there has been a considerable influx of German concessionaires, industrialists, and all kinds of individuals establishing commercial and industrial enterprises, transport associations, travel agencies and concessions” [3, p. 123]. The wording of that circular letter was quite specific: “The basis for German intelligence in Russia is the multimillion population of German origin (kulaks and “intelligentsia” elements of German colonies in villages and cities), which is the primary source of information for German intelligence…” [3, p. 124].

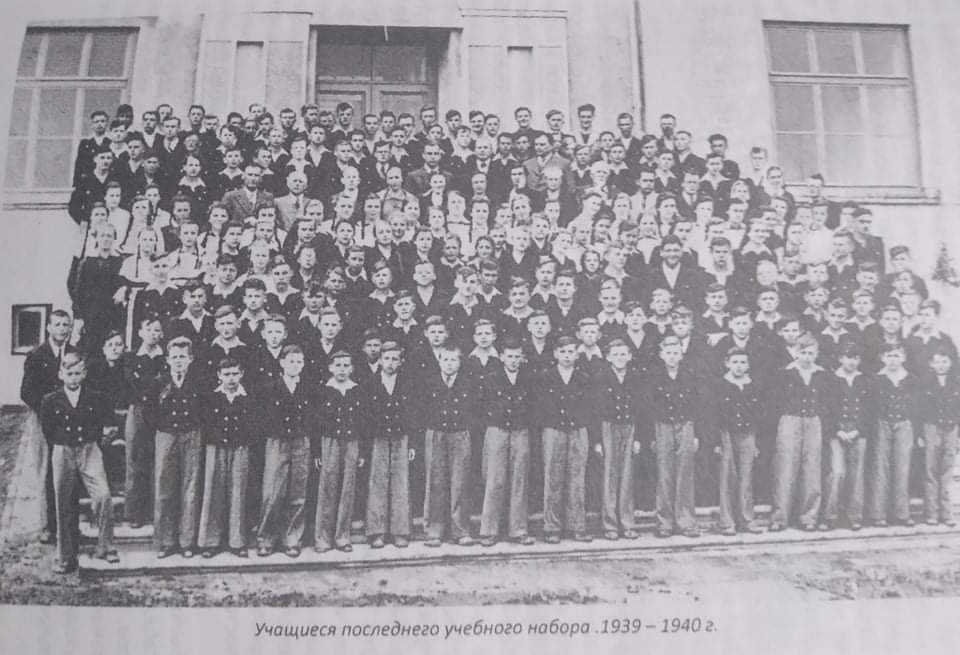

All of these allegations regarding German “spies” and “kulak elements” fueled chauvinistic sentiments against the German population residing in the Soviet Union. Consequently, the Politburo, the Organizational Bureau, and the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the CP(b)U passed numerous resolutions aimed at dismantling the central hubs of German residence. Moreover, two significant resolutions were adopted: “On the contamination of the Khortytske German Engineering College with class-hostile elements” (April 7, 1935) and “On the Odesa German Pedagogical Institute” (December 4, 1937). These resolutions led to the closure of German national educational institutions, with several faculty members and students facing repressions. Administrative-territorial entities, including German national districts and village councils, underwent reorganization [9, p. 77].

Documents such as the Minutes of the meeting of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the CP (b) U reveal that the Soviet authorities outright labeled ethnic Germans as “fascists” and “fascist nationalist elements,” holding them responsible for the failure of collective farming initiatives [10, p. 178].

In 1937, the Odesa region, which housed about 120,000 ethnic Germans – with 50,000 residing in the German national districts of Spartakiv, Zeltsia, and Karl-Libknechtiv – became the target of extensive punitive measures. Following a directive from the Odesa regional committee of the CP(b)U, around 5,000 families, labeled as “anti-Soviet fascist activists,” were forcibly deported to distant areas of the Soviet Union, including Kazakhstan and Siberia [2, p. 92].

There were also instances where the relocation was directed towards Germany. On September 15, 1940, a Soviet-German resettlement commission arrived in the town of Sarata, located in the Odesa Region. An official announcement, published in both German and Russian, declared that all Germans aged 14 and above were slated for deportation to Germany [5, p. 148].

The plight of ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union intensified, reaching its peak with the massive deportations that ensued following the inception of the German-Soviet war on June 22, 1941. Beyond the previously stated accusations, Germans were now also charged with harboring criminal intentions. As stipulated in paragraph 2 of the NKGB Directive No. 127/5809, which outlined the responsibilities of state security agencies in light of the war with Germany [12, p. 35], the grounds for the arrest were “the elimination of counter-revolutionary and spy elements.” The Soviet security forces identified these elements as the ethnic Germans residing in the Soviet Union.

On August 12, 1941, the USSR Council of People’s Commissars and the Central Committee of the CPSU enacted a joint resolution No. 2060-935ss “On the Resettlement of Germans of the Volga Region in Kazakhstan.” Two days later, Directive No. 00931 from the Supreme Command Staff “On the Formation and Tasks of the 51st Separate Army” in Crimea instructed “to immediately clear the territory of the peninsula from its residents — Germans and other anti-Soviet elements.” This directive led to the rapid deportation of around 60,000 Germans in Crimea to the Ordzhonikidze region [11, p. 34].

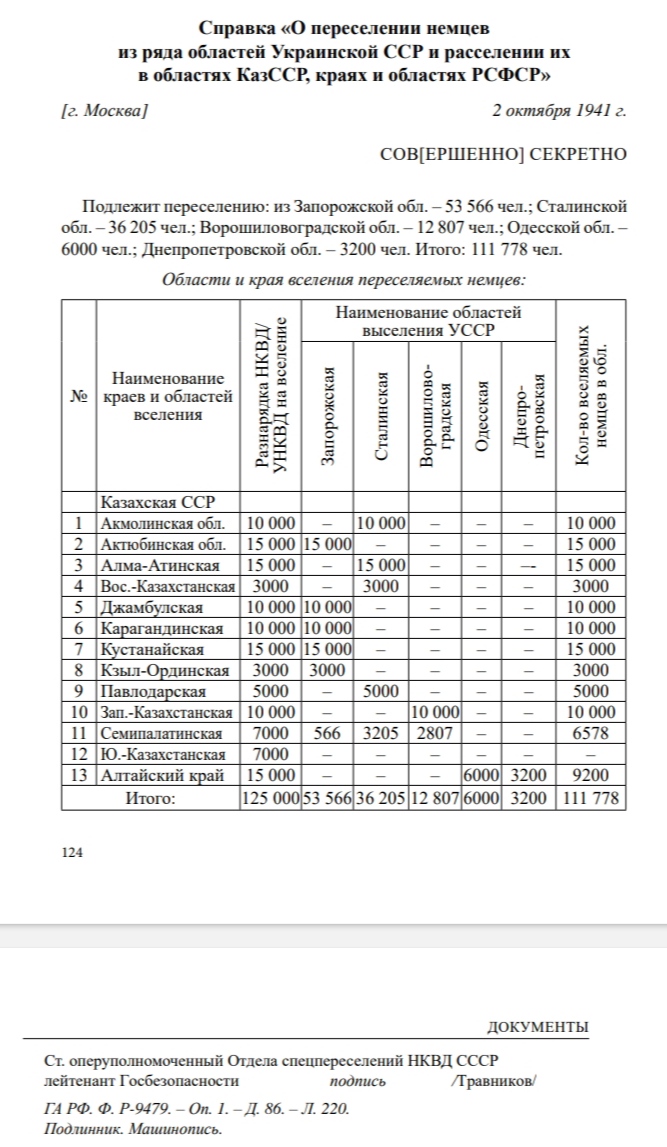

On August 31, at the suggestion of the NKVD, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) approved a resolution “On Germans Living in the Ukrainian SSR,” initiating a comprehensive deportation of Germans from areas of the republic not yet seized by German forces. According to the order of the Special Resettlement Department of the NKVD of the USSR issued on October 2, 1941, plans were set to deport 53,566 individuals from Zaporizhzhia, 36,205 from Stalin, and 12,807 from the Voroshilovgrad regions to the Kazakh SSR. Additionally, 6,000 people from the Odesa region and 3,200 people from the Dnipropetrovsk region were designated for resettlement in Russia’s Altai region [11, p. 35].

The active combat operations of the German-Soviet war halted these deportation proceedings. However, in 1944, as the Soviet government reclaimed lost territories, the deportations resumed, now further justified by accusations of Nazi collaboration.

Liliia Shpilman, whose father was a deported ethnic German, recalled: “From November 1942 to December 1945, my father served in the labor army… Stationed in the town of Uzlova in the Tula region, he worked tirelessly in the coal mines. By the end of it, he weighed a mere 35 kilograms, a grown man. I don’t know how he survived; his body must have been strong. Even after the war, he remained under curfew supervision until 1956.”

Alla Krukovska (Shetle), another child of a deportee, mentioned: “In 1941, there is a record here: ‘Dismissed due to relocation to another republic.’ (Looking through her father’s documents). This is how the deportation began. We found ourselves housed with Kazakhs in a passage room within a random dwelling. Behind the stove was a tuberculosis patient… My father was very creative, always coming up with something, he worked in a plantation there, and invented a plow that would dig up seedlings. But very little time passed, and my father was taken to work in the labor army” [8].

In summary, the Soviet authorities orchestrated the forced deportation of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans residing in Ukraine. They were taken to Central Asia and Siberia, with men aged 16 to 60 and women aged 17 to 55 being conscripted into labor armies, assigned to NKVD work columns and special settlements. Tragically, a third of these deportees succumbed to the harsh conditions, perishing from starvation and backbreaking labor. Although the special settlement regime was dissolved in 1955, the prohibition on returning to Ukraine, from where ethnic Germans were deported, remained in effect until January 9, 1974 [8]. Despite the lift of the ban, only a fraction chose to return to Ukraine; many either stayed in the places they had been deported to, spanning generations, or sought new beginnings in Germany.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Subscribe for our news and update

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

Explore the tragic history of mass deportations in the west of Ukraine from 1939 to 1941, orchestrated by the Soviet regime.

Investigate the Soviet-era policies that led to mass relocations. A detailed look at the struggles and resistance of Ukrainian peasants.

and we will send you the latest news