Deportations of Ukrainians in the 1930s. The policy of dekulakization

Investigate the Soviet-era policies that led to mass relocations. A detailed look at the struggles and resistance of Ukrainian peasants.

Encyclopedia

Throughout its reign, the Soviet government frequently resorted to deportation as a governance strategy in all territories it occupied or influenced. From 1939 to1990, during the Soviet occupation, the inhabitants of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia experienced forced deportations from their homes. The roots of this interest trace back to the early days of the USSR in the early 20th century, a time when the newly independent states emerged from the territories of the former Russian Empire, which were embroiled in battles for independence against both the White Guards and the Red Army. Moscow had always viewed these independent states as areas of geopolitical interest.

However, it was not until after World War II that the Soviet government was able to fully seize control over the Baltic States, imposing a regime characterized by dictatorship, forced labor, and deportations for the population.

The pivotal moment that set the stage for these deportations came in August 1939 with the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the USSR[1]. A secret additional protocol to this pact earmarked [2] Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia as being within the Soviet sphere of influence, effectively marking the beginning of the deportation processes in these then-independent Baltic States.

In the book “One Hundred and Forty Conversations with Molotov” penned by Russian writer F. Chuev, this event is described in the following way: “We [the Soviet leadership and Soviet Foreign Minister V. Molotov] solved the issue of the Baltic States, Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and Bessarabia with Ribbentrop in 1939. The Germans were reluctant to accept that we would annex Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Bessarabia. When I [V. Molotov] was in Berlin a year later, in November 1940, Hitler asked me: ‘Okay, you’re putting Ukrainians and Belarusians together, okay, Moldovans, that’s still explicable, but how will you explain the whole world about the Baltic States?’. ‘We will explain it,’ I told him. Both the communists and the Baltic peoples supported joining the Soviet Union. Their ‘bourgeois’ leaders arrived in Moscow for negotiations, but they refused to sign the accession to the USSR. In 1939, the Latvian foreign minister came to us, and I told him, ‘You won’t come back until you sign the accession to us’” [3, p. 15].

Vytautas Landsbergis, who served as the first chairman of the Lithuanian parliament, stated in 1990, “The fate of the Baltic States was not theirs to decide. The invasion was planned ahead of time. In 1938–1939, the Soviet headquarters printed military maps on which our countries were designated as the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian SSRs. They did this in advance so that they would not have to reprint them later. All troop movements were based on these maps” [4].

The occupation of the Baltic States unfolded gradually, starting in late September 1939 when Soviet warships appeared off the Baltic coast and aircraft began infringing on the airspace of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia to collect intelligence. At that time, the military forces of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia had 28,000, 23,000, and 11,000 soldiers respectively, significantly outnumbered by the Soviet troops. The vulnerability of the Baltic States in the early stages of World War II compelled their leaders to enter into military assistance pacts with the Soviet Union in early 1939. These agreements allowed the USSR to establish bases in the Baltic region and deploy around 75,000 soldiers there.

By the end of May 1940, roughly six months later, Soviet forces amassed near the Baltic borders under the guise of training exercises. This force comprised about 435,000 personnel, up to 8,000 artillery pieces and mortars, more than 3,000 tanks, over 500 armored vehicles, and 2,601 aircraft. The invasion began on June 15 with the Soviet army entering Lithuania, followed by the occupation of Latvia and Estonia on June 17, in line with the provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact [1]. This maneuver allowed the USSR to finally exert control over the Baltic States, a long-standing objective since its formation.

Despite attempts by the Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian forces to resist, they were overwhelmed by the superior power of the invaders and chose to surrender to save their troops. The populace, unhappy with the communist rule, voiced their protest. The Soviet regime responded with a heavy hand, employing brutal tactics they had used in other occupied nations to suppress dissent. This included persecution, imprisonment, and even extermination, with forced deportations to the Russian Far East being the most frequent punitive measure.

On May 14, 1941, the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) alongside the USSR Council of People’s Commissars enacted Secret Decree No. 1299-526, titled “On the Expulsion of Socially Alien Elements from the Baltic Republics, Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and Moldova.” This decree outline the specific groups of people from Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia who were targeted for deportation, including:

The decree clarified that “incriminating materials” referred to evidence of anti-Soviet actions or connections to foreign intelligence agencies [9, 167].

The exact number of individuals deported from Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia remains unclear. According to the NKVD’s plan dated June 11, 1941, the figures stood at 46,557 families, 4,159 criminal offenders, and 794 prostitutes, totaling 74,395 people. This count includes 13,780 individuals (and their families) deported for political reasons, in addition to 691 criminals and prostitutes from Estonia.

Occupation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania by the Soviet Union. The blockade of the coast by the navy and the operation of the ground forces in mid-June 1940: Estonian Institute of Historical Memory. https://mnemosyne.ee/

Following the swift invasion of Estonia, the Soviet occupation authorities first targeted members of the national government for removal. The initial deportations in 1940 included high-ranking officials such as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, Johan Laidoner (on July 19), and the president of the republic, Konstantin Päts (on July 30). Tragically, all past Estonian heads of state faced persecution. Four — Friedrich Karl Akel, Jüri Jaakson, Jaan Tõnisson, and Jaan Teemant — were executed, while another four died in prison. Out of 78 former ministers, 64 were arrested by the occupation administration, and all positions in state agencies were filled by Russians.

Mass deportations began on June 14, 1941, when the new government delineated the groups slated for forced removal, making the onset of what is regarded as the first act of genocide perpetrated by the Soviet regime against the Estonian people. Initially, the elite families of the Estonian society, including 2,578 children, were the primary targets. People were forcibly removed from their residences, whether homes, apartments, or estates, and herded to railway stations. From there, they embarked on a harrowing journey to the Russian Far East, packed into trains under horrific conditions that led to the death of thousands en route. The survivors, who faced a brutal adjustment to a new climate and deplorable living conditions, often succumbed to hunger and diseases shortly after reaching their destinations.

A telegram discovered in Riga after the Red Army withdrew from Latvia revealed that Moscow targeted to deport 11,102 individuals from Estonia [12, p. 366].

The testimonies of the victims of deportation confirm it was conducted aggressively. Johan Vaabel,born in 1939, describes the deportation of his family to Siberia: “My family and I were taken from Mulhimaa (a region in southern Estonia) on June 14, 1941. My father August Vaabel, my grandmother Lena Vaabel, my mother Helma Vaabel, and me. We were sent to the village of Kosotyapka in Tomsk Oblast, Russia. My father was taken away from us and sent to the Gulag, where he died at the age of 38. I received information about life in this camp from Mats Laarman. Everything in the camp was organized in such a way that you could only live there for six months. Those who survived longer were given some form of forest work. They deliberately sent them there on foot by the longest road, and when they saw that the person was likely to die soon, they sent them to walk through the swamp. If the direct path was five kilometers, it was eight kilometers through the swamp. They hoped that a person would die on the road, in the swamp area. The dead bodies were piled up like firewood. During the spring floods, they drowned there… After a while, my mother and I received a permit, and we settled in the village of Novososnovka, Chayinsky district, Tomsk region of Russia. There was a relatively large number of Estonians…” [10].

Vello Malken, born in 1938, recalls: “My father was taken away when I was 3,5 years old. He was a veteran of the Estonian War for Independence… In the morning, on June 14, 1941, a car arrived, and Soviet soldiers told my father that he had two hours to pack. We were being evicted to Siberia. The Soviet soldiers advised us to pack winter clothes, non-perishable food, and tools such as drills and hammers. On the way, our train was severely delayed because the Germans were already advancing on the territory of the Soviet Union… When we reached the place of deportation in the Far East of Russia, my parents were forced to work on a collective farm with the deported ‘kulaks’. There were also many Lithuanians and Estonians there. The first winter was the hardest. The city council gave out one loaf of bread per person for week…” [11].

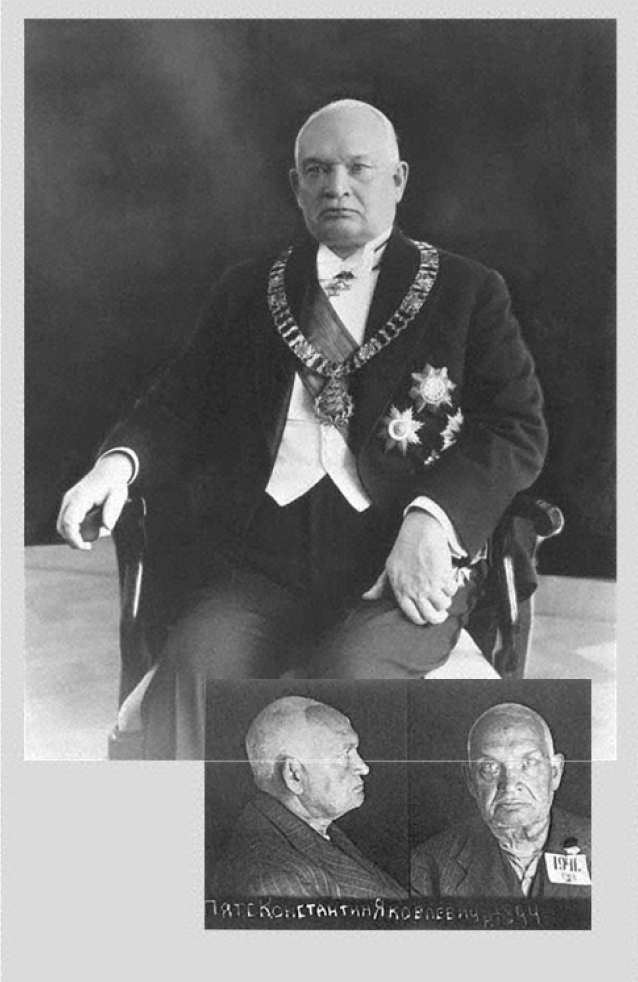

Photo of the President of the Republic of Estonia, Konstantin Päts, before and after his Soviet imprisonment. [6]

In June 1941, the Soviet regime forcibly relocated 15,400 Latvians to Siberia and Kazakhstan, marking the first mass deportation from Latvia [13]. Carried out by the People’s Commissariat of National Security of the LSSR, with the support from LASCO and the Baltic Headquarters of the Special Military District, the operation also involved USSR convoy troops, the NKVD, police forces, and local party activists.

As before, the deportations were largely driven by class distinctions, targeting individuals labeled as counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet. Affluent citizens from the former Republic of Latvia were disproportionately affected, bearing the brunt of this brutal policy.

Deportation of Latvian citizens on June 14, 1941. Source: https://militaryheritagetourism.info/ru/military/topics/view/59

Before being deported, many Latvians were first detained Special sessions convened by the MCC of the USSR determined the fate of these individuals, with outcomes ranging from execution to imprisonment in camps for periods of 3 to 10 years. Some who were sentenced to death were killed even before the formal execution could take place. Of the over 3,400 Latvian citizens arrested on June 14, 1941, most died in prisons.

Among those arrested were many villagers, who were repressed mainly as members of the Latvian Security Organization. Survivors of the initial imprisonment, including those held in “filtration camps,” were later exiled to areas such as the Krasnoyarsk Territory, Novosibirsk Region, and Northern Kazakhstan. There, they endured force labor in forestries, collective and state farms, all under the strict supervision of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. The harsh conditions and brutal treatment led to do the death of over 1,900 deported Latvian citizens in the camps [14].

1941 A deportation wagon at the Torniakalns station. Photo: Edgars Ražinskis.2021.

Source: https://militaryheritagetourism.info/ru/military/topics/view/59

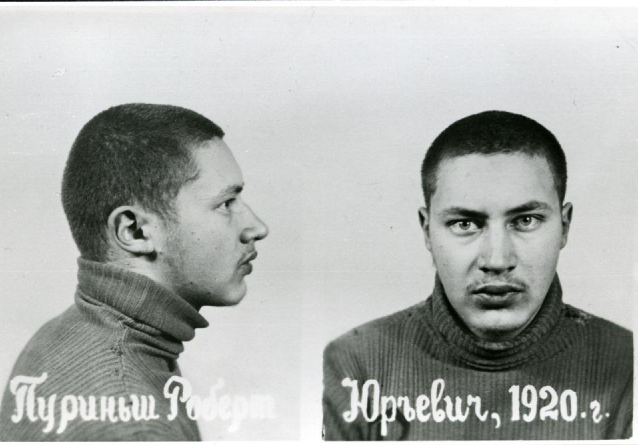

Stories of survivors bear witness to the inhumane treatment endured by those arrested and deported in the USSR. One such account is that of Latvian Robert Purinsh, born in 1920. In June 1940, amidst the Soviet occupation of Latvia, Purinsh joined the national resistance movement Tēvijas Sargi (Guardians of the Fatherland). His arrest came on November 18, 1940, the day before Latvia’s Independence Day, following his distribution of anti-Soviet leaflets.

As Nazi forces approached Soviet-occupied Latvia, Purinsh, along with other prisoners, was moved deeper into the USSR — first to Petropavlovsk and later to labor camps in Omsk. In 1943, Robert was released from the labor camp due to his dystrophy, which prevented him from working. He was then sent to the Kazakh SSR, where he lived for two years. Although he managed to return to the Latvian SSR in 1946, his freedom was short-lived: he was arrested again in 1950 and deported to Siberia the following year. It wasn’t until 1955 that Purinsh could return home [15].

Purinsh’ harrowing experience was far from unique. The Soviet regime conducted ruthless purges in the occupied territories, subjecting the population to repeated cycles of arrest, deportation, torture, and forced labor, with particular focus on those who resisted or were perceived as potential threats to the Soviet authorities.

Robert Purin – a photo from the NKVD criminal case files during his second arrest in Riga. Source: “Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.” [16]

Subscribe for our news and update

The Soviet regime orchestrated mass deportations of Lithuanian citizens, with documented plans revealing the scale of these operations in the Lithuanian SSR. Records from June 6, 1941, show that 15,692 individuals were arrested and deported based on the NKVD and NKGB lists [7]. A report dated June 11, 1941, noted that 22,252 people were slated for deportation. However, the deportations carried out on June 13–14 saw even more Lithuanians being forcibly removed, with the total reaching 34,000 individuals [15].

Survivor Ms. Dalia Grinkevičiūtė offers a first-hand account of the horrifying events that unfolded: “On June 14, 1941, at three o’clock in the morning, mass arrests and deportations began simultaneously in all the Baltic countries — Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. On the orders of Moscow, Chekists from Belarus, Smolensk, Pskov, and other places were mobilized to perform this task. Eventually, the overcrowded trains moved eastward, transporting huge masses of people, most of whom were never to return. Teachers of primary and secondary schools, university professors, lawyers, journalists, families of Lithuanian soldiers, diplomats, various office workers, farmers, agronomists, doctors, businessmen, etc… I remember those who died in Trofimovsk (Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), modern Russian Federation): Teacher Staniskis from Kaunas, teacher Gediminas Balčys from Daugiai, Asmontienė, Lukosevičienė from Siauliai, Raibikienė from Kalvariai, Balazarienė from Kėdainiai, a twenty-five-year-old giant named Zabuka, twelve-year-old Jonukas Gedrikis from Marijampolė, Barniškienė, Mikoliunienė, young Baltokas, Volungevičius, Geleris, Klingmanienė, Krikštany from Kaunas. […] Many Lithuanians whose names I do not remember or have never even known lay in one mass grave. No fresh flowers were ever placed there, and no mourning music was ever played” [20].

The June deportations left an indelible mark on Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, impacting nearly every segment of the population, predominantly those linked to the elite circles of these nations. Despite the dinstinct cultures, histories, and mindsets of each Baltic state, they share a unified tragic history shaped by the Red Terror.

To honor the victims and reflect on this dark chapter,, each Baltic State observes a Memorial Day on June 14. Estonia commemorates the day as the “Day of Remembrance of the June 14 Deportation” (14 juuni küüditamise mälestuspäev), Lithuania as the “Day of Mourning and Hope” (Gedulo ir vilties diena), and Latvia as the “Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Communist Terror” (Komunistiskā genocīda upuru piemiņas diena).

The grim period of 1940-1941 saw staggering number of forced deportations: 34,000 in Latvia, 60,000 in Estonia, and 75,000 in Lithuania, leaving a deep scar in the collective memory of these nations [15].

Deportees from the city of Varėna (southern Lithuania) work at a building. Grishevo, Irkutsk Oblast, 1953. Source: Center for the Study of Genocide and Resistance of Lithuanian Residents. [17]

Deported at the distribution center in the village Buret, Irkutsk region. April 1949. [18]

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Investigate the Soviet-era policies that led to mass relocations. A detailed look at the struggles and resistance of Ukrainian peasants.

Explore the tragic history of mass deportations in the west of Ukraine from 1939 to 1941, orchestrated by the Soviet regime.

From Lenin’s directives to mass arrests, the 1920s deportations of Ukrainians reveal a dark chapter in Soviet history. Learn more here.

and we will send you the latest news