Deportation of Ukrainians in 1947. Operation “West”

Discover how the Soviets systematically deported millions from the west of Ukraine, erasing villages and cultural landmarks.

Encyclopedia

On April 28, 1947, thousands of Ukrainians were forcibly deported from what is now modern Poland. Almost 80 years have passed since “Operation Vistula,” during which 480,000 Ukrainians were forcibly deported from their historical lands, leading to the loss of a unique culture. Today, we remember it to acknowledge the complex Ukrainian-Polish relations and to seek reconciliation. This material explores the deportation operation “Vistula” and its consequences.

Operation “Vistula” marked the peak of a series of forced deportations of the Ukrainian population from their ancestral territories within Poland. This occurred as a result of the redrawing of Europe’s map after the end of World War II, leading to the forced resettlement or expulsion of many people.

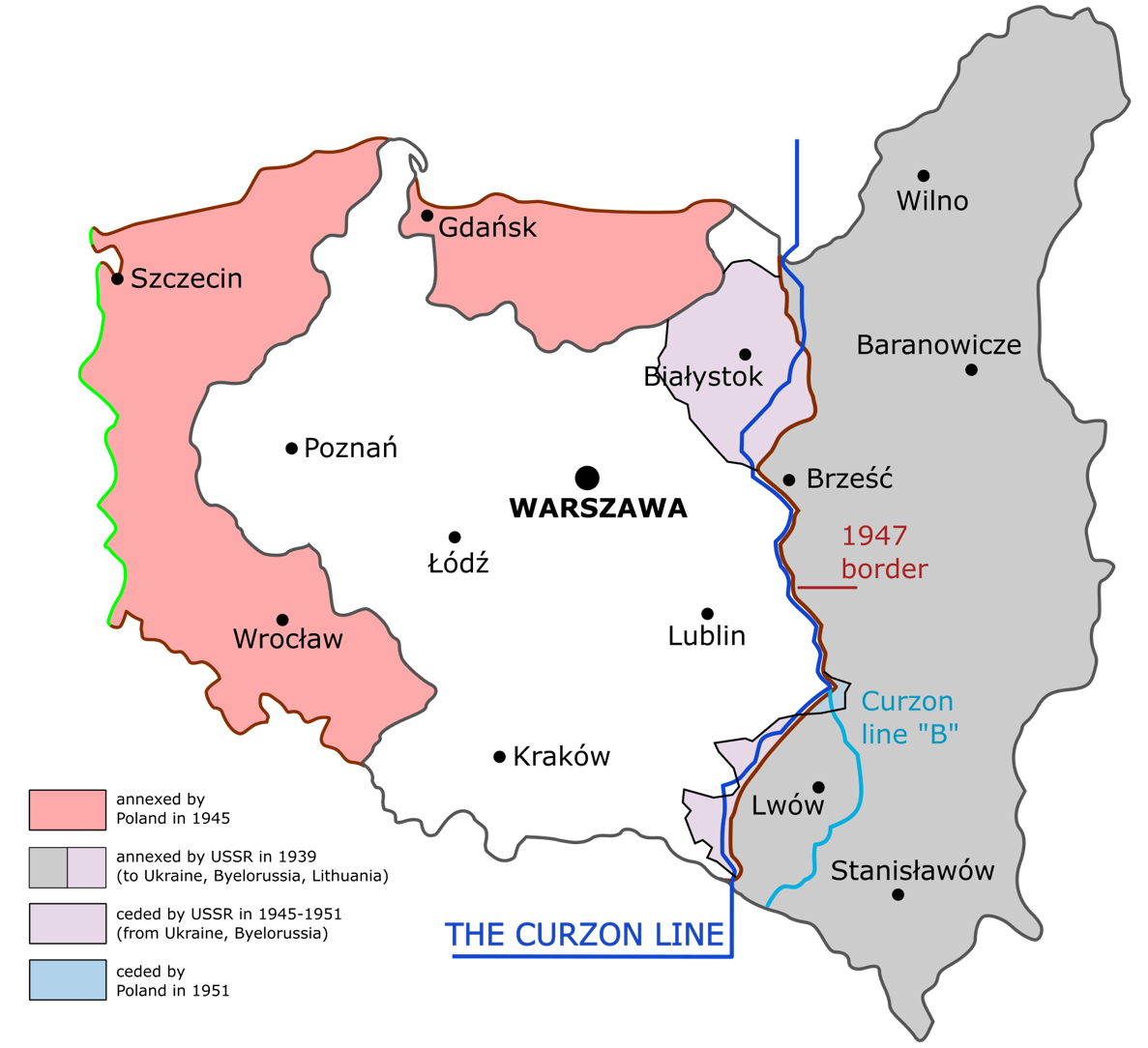

Under the terms of the Yalta Conference of 1945, Poland relinquished its pre-war territories to the Soviet Union, including historical Ukrainian lands, except for Lemkivshchyna, Western Boykivshchyna, Nadsyannya, Kholmshchyna, and Pidliashshia. In return, Poland acquired significant territories from Germany, including most of Pomerania, East Prussia, Silesia, and parts of Brandenburg, totaling about 20,000 km² — roughly the size of Slovenia — that were incorporated into the Soviet Union.

As part of the territory exchange, both Poland and the USSR intended to forcibly resettle hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians and Poles. The Polish authorities sought to create a stable mono-national state, while the USSR aimed to eliminate the Ukrainian national movement and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). The UPA’s armed resistance, supported by segments of the local population, challenged Soviet and Polish efforts to establish a new social order.

Map of the Territorial Division around Germany, Poland, and the USSR

In response, the Polish communist authorities, backed by the Soviet Union, initiated Operation “Vistula” to forcibly move the Ukrainian population from their historical territories to the western and northern regions of Poland. This strategy aimed not only to sever potential UPA supporters from their support base but also to dismantle the ethnic and cultural foundations of the Ukrainian national movement in the region. This was expected to diminish the Ukrainians’ capacity for self-identification and their demands for autonomy or cultural rights, thereby reducing the prominence of the “Ukrainian question” in Poland.

The murder of Karol Świerczewski, Deputy Minister of Defense of Poland and an important figure in the country’s communist leadership, served as a pretext for the deportation of Ukrainians. He was killed by Ukrainian insurgents on March 28, 1947. The communists portrayed this event as a clear demonstration of the threats posed by Ukrainians, justifying the perceived legitimacy of their forced deportation.

Preparations for the deportation had actually begun earlier, before January 1947, when the Polish General Staff implemented measures that included the registration of Ukrainian and mixed-origin families. In February, General S. Mossor developed a detailed deportation plan aimed at resettling Ukrainians in isolated units across the newly annexed territories to facilitate their assimilation [2]. This plan was approved by the State Security Commission on March 27 and forwarded to the Politburo for final endorsement. At a Politburo meeting the following day, several critical decisions were made:

Military units from the “Vistula” operational group were assigned to the operation, with between 20 and 50 soldiers per village. Additionally, the operation involved 5 infantry divisions of the Polish Army, 1 division of internal troops (KBW), 1 engineer regiment, 1 auto regiment, 1 police regiment, 1 aviation squadron, 2200 border guards, and 1,000 members of railway troops [2, p. 4]. Czechoslovak and Soviet army troops secured the borders while 17 reconnaissance aircraft patrolled the forests and mountains in the border area.

Operation Vistula in the Sanok Powiat. Soldiers of the Polish Army crossing the Sian River, 1947.

The deportation of Ukrainians during Operation “Vistula” unfolded in three stages:

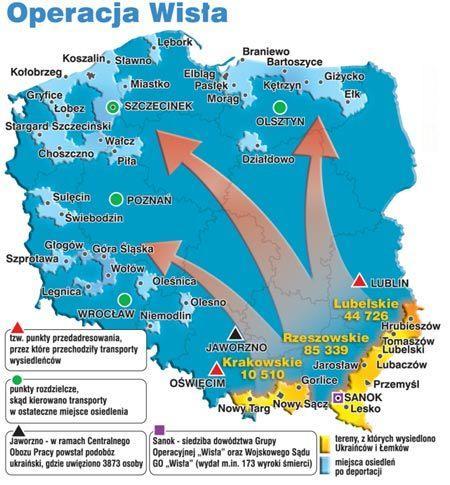

Map of the forced resettlement of Ukrainians in Poland

The deportation of Ukrainians was executed with abrupt precision. At 4 a.m., Polish military forces swiftly surrounded the settlements, informing residents of their impending relocation.

People were given just two hours to gather their personal belongings, limited to what could fit on two wagons. All other possessions, including homes, most furniture, equipment, and food supplies, were left behind and often confiscated by the military or looted by marauders. Villages, especially in the Bieszczady region (Western Beskids), were frequently burned and remain uninhabited to this day.

Polish officers observing people gathering their belongings before resettlement

Deported Evheniia Ivanyk from the village of Honyatyn in Hrubieszów Powiat recalled:

“And so, in haste, we began to tie up some bundles — whatever could fit into the chest or was readily available, preparing for the road. No one knew where we were headed or what fate awaited us. Father did everything silently. He was as white as a wall. Tears streamed down my mother’s face like peas. My sister and I helped our mother—to gather things and to cry…

Soon our modest belongings were loaded onto the wagon. Mother stood in the middle of the yard facing the house, and, clasping her head in her hands, she burst into bitter tears. Then she ran back into the house again and cried out as she bid farewell to our family home. She kissed the icon she left to protect the house, and then the walls, the gates, the threshold… Mother cried and so did we. Father stood in the middle of the yard, petrified, then he sat on the wagon, crossed himself and we left” [3].

A house in the village of Mushynka with a farewell inscription: “Farewell my house, farewell my home village of Mushynka, farewell village youth, farewell everyone.”

People were transported to collection points on wagons with their belongings. At these points, the Polish secret services compiled lists of individuals who might arouse suspicion, leading to possible arrests or restrictions on their resettlement, often limiting it to one family per settlement.

Deportation of Ukrainians as part of the “Vistula” action, April 1947

At the loading stations, under military escort, Ukrainians were loaded into cargo wagons. Officially, each wagon was to accommodate two families. However, in practice, this was often not adhered to. For instance, in Sanok, one train of 31 wagons transported 897 people along with 24 horses, 120 cows, 45 goats, 7 calves, and 2 foals. The trains traveled to transit points in Katowice, Auschwitz, and Lublin, and from there to distribution centers in Szczecin, Olsztyn, Wrocław, and Poznań. The journey could take anywhere from a week to 20–30 days, complicated by delays, list mix-ups, or congestion at railway stations, where instead of the planned 6 echelons, 15 to 20 might arrive.

At the transit points, waits could extend up to 20 days before proceeding to the final railway stations in the designated areas. There, delays continued; for example, a group of 22 deported Ukrainians from a nursing home arrived at their distribution area on June 19, 1947, but only reached their final destination in January 1948 [3].

Arrested representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and clergy, as well as individuals suspected of disloyalty towards the communist Polish authorities, were detained in the Jaworzno camp without any judicial decisions for extended periods.

Jaworzno, originally a German concentration camp and a subcamp of Auschwitz, comprised 15 wooden barracks and several brick buildings. Inside, the barracks were equipped with triple-tiered bunk beds made of planks. Spanning 6.6 hectares, the camp was surrounded by a double row of barbed wire and 12 guard towers fitted with machine guns and searchlights. A five-meter wall, constructed by the prisoners, separated the north side of the camp from the Krakow-Katowice road. Security was maintained by 300 soldiers and 18 officers from the Internal Security Department [4].

The concentration camp in Jaworzno. Post-war photo

Father Mitrate Stepan Dzyubyna described his experience in Jaworzno:

“The most painful was the hunger. We were constantly hungry, dry as ghosts. It was a cruel irony to later learn that entire wagons of food intended for prisoners were sold on the side… When I was transferred to the hospital, they told me that prisoners were given salted herring without a drop of water. This made them sick, and some even died.

Our main nourishment was a small ration of bread, and with it, a dark stinking liquid called ‘coffee.’ This was our breakfast and dinner, while lunch was, one could say, just plain water. All this led to the condition that after four months, prisoners were swelling from hunger, falling lifeless during the morning roll call. Sometimes, several corpses were carried out in one roll call. The bodies of the deceased, wrapped in paper bags, were taken out of the camp area in a two-wheeled cart to a nearby forest for burial” [8].

Mitre Father Stepan Dziubina

Violence was a daily reality for the deported imprisoned Ukrainians, who endured beatings at every opportunity — during meal distribution, in the bathroom, while queuing for the toilet, and particularly during interrogations. It was common for Ukrainians to return from interrogations with broken ribs, knocked-out teeth, torn-off fingernails, or fingers calloused from torture. The extreme torture drove some to insanity, compelling them to throw themselves against the camp’s electrified wires. For many Ukrainians, Jaworzno became a living hell, a continuation of the horrors experienced during and after the war, including the loss of their homes due to forced deportation.

The communist regime in Poland did not conceal its intention to fully assimilate the deported Ukrainians into the new socio-cultural environment. The deported Ukrainians were settled in locations at least 30 km from the administrative centers of the voivodeships and 50 km from the national border. It was prohibited to establish communities where more than one deported family could live together.

The authorities especially targeted the deportees’ religious practices, actively obstructing the activities of the Greek Catholic clergy, preventing the creation of new parishes, and directing the faithful to Roman Catholic churches. Despite government promises of prosperous farms vacated by Germans, many Ukrainians found themselves in damaged houses, often shared by several families.

Oleksandr Kolyanchuk recalled:

“They dispersed us throughout the county to places like Jelonki, Ryhlyki, Skowronki, Wola Mlynarska, Wilczaty, and also Dobry. They gave us a small room (3 by 4 meters) for four families. Our wives cooked in the yard while the men slept in the hay. They spoke of us in the worst terms, saying we were thieves and bandits who had tormented Poles (on our lands, it was the other way around)” [3].

As a result of Operation “Vistula,” the Polish communist authorities removed the Ukrainian population from the southeastern voivodeships of the country, scattering 140,575 Ukrainians and Poles married to Ukrainians across western and northern Poland (about 14,000). A total of 315 individuals were arrested and convicted, with 173 executed. By the end of 1947, an additional 10,000 people were captured and deported [3].

In 1956, during the era of de-Stalinization, Ukrainians were nominally given the chance to return to their historical territories, but in practice, this proved extremely difficult. Starting the return process required official permission from Polish government structures, but former homes and lands were already occupied by new residents. Ukrainian families could not unite to organize returns or conduct actions to draw attention to their plight. The resettlement policy focused on quick and effective assimilation, preventing any discussions about autonomy or cultural rights, as isolated living by one family in a village did not raise the “Ukrainian question” in Poland.

Operation Vistula and the actions of the communist government not only severed the social and cultural ties of Ukrainian communities but also left a lasting trauma in the collective memory of the people. In today’s context, similar actions by the Russian government involve forced deportations of Ukrainians. These actions not only violate international norms but also inflict significant grief and suffering, exacerbating collective traumas. Stopping the deportation of Ukrainians by Russia and working towards their return is our collective responsibility to ensure historical justice.

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Subscribe for our news and update

Discover how the Soviets systematically deported millions from the west of Ukraine, erasing villages and cultural landmarks.

From Lenin’s directives to mass arrests, the 1920s deportations of Ukrainians reveal a dark chapter in Soviet history. Learn more here.

Investigate the Soviet-era policies that led to mass relocations. A detailed look at the struggles and resistance of Ukrainian peasants.

and we will send you the latest news