Encyclopedia

Deportation of Ukrainians in 1947. Operation “West”

In 1944, the Soviet army reoccupied the West of Ukraine. As some troops advanced toward Berlin, others stayed behind to reinstate communist rule in the region. The primary goal of the special services and security forces was to suppress Ukrainian independence movements, specifically the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) and the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), as well as their supporters. According to the report “On the results of the struggle of the bodies and troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs-MGB against the OUN underground in the western regions of Ukraine” (1944–1953), various Soviet agencies and military units — including the NKVD, NKGB, SMERSH, internal and border troops, Soviet army units, partisan units, fighter battalions, police and armed groups of Party-Soviet activists—were instrumental in dismantling Ukrainian resistance [1]. Deportation was a key strategy used by the Soviet regime in this campaign.

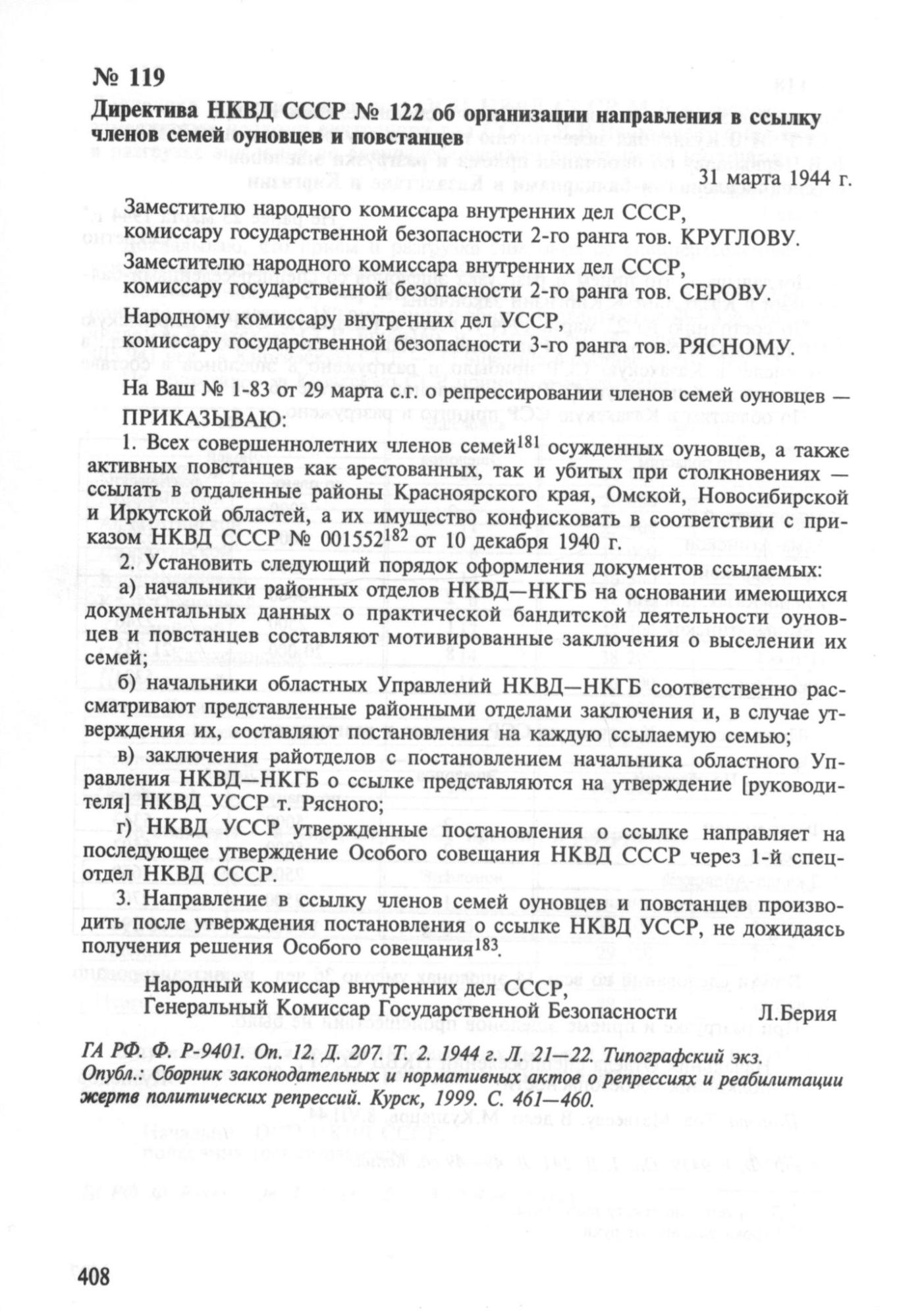

In a Directive from the NKVD of the USSR Lavrenty Beria, the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR, stated: “All adult family members of convicted OUN members, as well as families of active insurgents — whether arrested or killed in clashes — should be exiled to remote areas of the Krasnoyarsk Territory, Omsk, Novosibirsk, and Irkutsk Regions, and their property should be confiscated… Family members of OUN and insurgents should be exiled immediately after the NKVD of the USSR approves the exile resolution, without waiting for the decision of the Special Meeting” [10, p. 408].

Such extreme measures were taken in response to the active resistance of OUN and UPA members against the Soviet occupation. These groups engaged in guerrilla warfare, mass mobilization, and opposed both the suppression of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and forced collectivization. In 1944–1945 alone, UPA units carried out 14,500 military and sabotage actions [2]. To counter this, Soviet forces launched the “Great Blockade” January to April 1946. This large-scale operation aimed to isolate UPA members and supportive communities in Galicia and Volyn. Deploying 585,500 troops along with tanks and aircraft, the operation effectively cut off the UPA from its supply bases and forced them to operate under challenging conditions. As a result, the resistance movement’s numbers dropped by nearly 40% during this period [3].

To further undermine local support for the UPA, Soviet authorities reverted to tactics used during the first occupation of the West of Ukraine from 1939 to 1941— mass deportations. Before the Nazi invasion, over 3 million Ukrainians had already been deported to Russia or Kazakhstan [11].

In 1944, 4,724 families, totaling 12,762 people, were exiled from Volyn, Drohobych, Lviv, Rivne, Stanislav (now Ivano-Frankivsk), and Ternopil regions. This “deep cleansing” of the West of Ukraine to remove the OUN and UPA supporters continued in subsequent years. Between 1944 and 1946, a total of 14,728 families, or 36,608 individuals, involved in the national liberation movement were deported from the region [2].

While the Soviet leadership was already fighting insurgents through punitive operations and mass evictions, they deemed these measures insufficient. As a result, in early May 1947, they initiated their largest deportation campaign of the period, known as Operation West. The first normative act, MGB of the Ukrainian SSR Directive No. 50, was signed on May 14, 1947 [4]. A subsequent order on June 1 outlined the task of identifying “family members of active OUN and UPA members”.

The operation was scheduled for October of that year. Deputy Minister of State Security of the USSR Afanasii Blinov, Head of the Main Directorate of the USSR MGB Troops Petro Burmak, and Lieutenant General Oleksandr Vadis were dispatched to Ukraine to supervise the operation. They were later awarded for its “successful” execution. Following directives from Moscow to “cleanse” Western Ukraine of “enemies of the people and their accomplices”, local MGB and MIA units, along with employees of the district committees of the CP(B)U, began compiling lists of candidates for deportation. Military units were assigned specific settlements, and both motorized and horse-drawn transport were arranged [2]. In total, 15,750 senior law enforcement officials were involved in the operation [3].

![Map of Operation “West”. [5].](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/image5.png)

Map of Operation “West”. [5].

Operation West commenced in utmost secrecy on October 21, 1947. It began at 2 a.m. in Lviv and expanded to all regions in the west of Ukraine by 6 a.m.. MGB troops secured all central and connecting roads, as well as junction stations. People were directed to six designated collection points in Lviv, Chortkiv, Drohobych, Rivne, Kolomyia, and Kovel. Within two days, the majority of the families identified as part of the “special contingent” were deported.

The operation concluded on October 26, 1947. A total of 26,682 families, comprising 77,808 individuals, were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan. Over 60,000 of these deportees were forcibly assigned to the coal industry, specifically to locations like Kuzbassugol, Chelyabinskugol, Molotovugol, Karagandavugol, Vostoksibvugol, and coal mines in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, Russia. The rest were placed in industrial and agricultural jobs in the Omsk region, Russia [3].

People weren’t just deported to the far reaches of the USSR and Siberia; many were also sent to Ukraine’s own central and eastern regions, like Dnipro and Mykolaiv. This move was made in response to the post-war demographic crisis and to fill labor gaps on collective farms in these parts of Ukraine. Early 1960s KGB records of the Ukrainian SSR confirm the deportation of 77,808 individuals.

The Soviets didn’t stop at individual deportations; they also targeted entire villages known for their support of Ukrainian independence movements. Take Hryva village in the Volyn region for example. In 1951, MGB agents uncovered several UPA hideouts and identified key members like Andrii Mykhalevych (“Kos” or “Denys”), Klym Tymoshyk (“Roman”), and Pelageya Herasymuk (“Olya”). When captured, Mykhalevych choose to detonate a grenade, destroying evidence and killing everyone in the hideout, rather than face capture. [6, p. 121].

After uncovering the UPA hideouts, the Soviets accused the entire village of Hryva of anti-communist activities. They ordered the deportation of all residents and the destruction of the village itself, resulting in the forced removal of around 1,500 people.

Andrii Mikhalevich “Kos”.

The source of the photo: Ukrainian Liberation Movement – OUN and UPA. https://www.facebook.com/uvr2017

Residents vividly remember the ordeal. Roman Tereschuk recalls, “Cars flooded the village to carry belongings to the station. People took whatever they could: dismantled houses, equipment, jugs, pets, clothes… We were told to come to Manevychi station. I remember spending three rain-soaked days there. Tents were put up for us kids, while adults stood in the rain on guard. We were herded into freight cars, jumbled together with livestock and belongings… The journey took several days and happened in the fall. The village was relocated to the east of Ukraine six times in total. I was nine years old at the time.”

A monument on the place of the village Hryva.

Photo source: https://kamin.rayon.in.ua/ [8].

“We were the last to arrive, the sixth group,” says Oliana Dmytrivna, Roman Tereshchuk’s wife. “I remember those freight wagons too. We were taken to Hubynykha station, and from there, we drove to Magdalynivka. I was six years old at the time” [9, p. 5].

In the photo — Tereshchuk family – Olyana Dmytrivna and Roman Terentyevych. [5]

The Soviet occupation government systematically devastated the local population in the west of Ukraine through multiple waves of ethnic cleansing and deportation. In the years following the war, they escalated their efforts, erasing entire villages and cultural landmarks after forcibly removing the residents. This was part of a broader strategy to erase Ukraine’s historical memory and annihilate its national identity.

Today, Russia continues this grim legacy. Just in the past year, 2022, Russia had demolished at least 553 Ukrainian cultural sites, deported between 2.5 to 4.7 million Ukrainians, and completely razed cities like Mariupol, Vuhledar, Maryinka, Volnovakha. The Russian war against Ukraine persists, along with the ongoing destruction of its cultural heritage and people.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Documents

Directive of the NKVD of the USSR No. 122 on the organization of exile of family members of OUN members and insurgents. [10, 408]

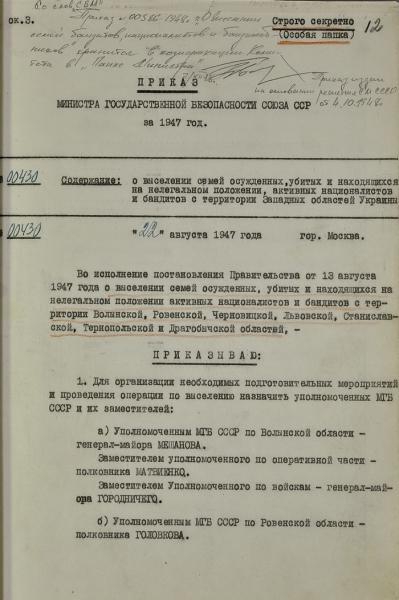

The Order of August 22, 1947 “On the Eviction of Families of Convicts, Murdered, Illegal, Active Nationalists and Bandits from the Territory of the Western Regions of Ukraine” signed by the Minister of State Security of the Soviet Union Viktor Abakumov. [5].

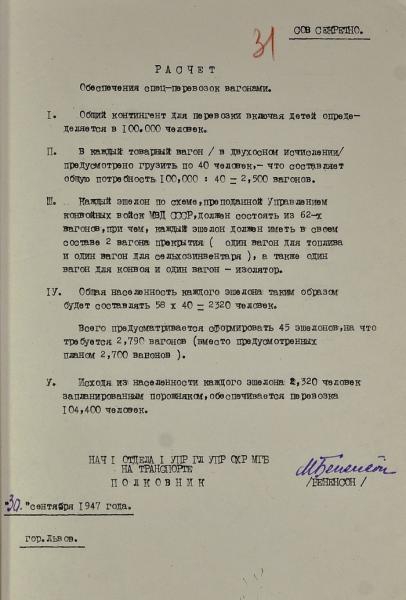

3.Assessment of the number of special transportation services, taking into account the possibility of deportation of 100 thousand people. [5].

4. The results of Operation West as of the end of October 1947. Infographic by Oleh Opashyn for “Local History” [2].

Sources & References:

- Когут А. Особливості депортації українського населення під час операції “Запад” (за документами ГДА СБУ). Дисертація на здобуття ступеню кандидата історичних наук. Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка, 2020.

- Бажан О. Операція “Захід”. URL: https://localhistory.org.ua/texts/statti/operatsiia-zakhid/

- Примаченко Я. Операція “Захід”. URL: https://www.jnsm.com.ua/h/1021Q/

- Когут А. Операція «Захід» у контексті радянських депортацій із Західної України 1940-1950-ті рр. // Вирване коріння: дослідження, документи, свідчення. К., 2020.

- Роковини операції “Захід”: Опубліковано документи МГБ про депортацію українців. URL:https://tvoemisto.tv/news/rokovyny_operatsii_zahid_opublikovano_dokumenty_mgb_pro_deportatsiyu_ukraintsiv_89278.html

- Антонюк Я. Андрій Михалевич – “Денис”, “Кос”, “13-й”: життя у боротьбі за самостійну Україну. Минуле і сучасне Волині та Полісся. Сереховичі та Старовижівщина у світовій та українській історії. Науковий збірник. Випуск 53. Матеріали LІІІ Всеукраїнської історико-краєзнавчої наукової конференції, присвяченої 24-й річниці Незалежності України, 20 травня 2015 року, смт. Стара Вижівка – с. Сереховичі. Упоряд. А. Бондарчук, А. Силюк. – Луцьк, 2015.

- Симонович Є. М., “Родовід Симоновичів”. — Рівне, 2004.

- Шмигін М. Переселення по-радянськи: хати в селі на Камінь-Каширщині поруйнували, а селян вивезли в іншу область. URL:https://kamin.rayon.in.ua/topics/460333-pereselennya-po-radyanski-khati-v-seli-na-kamin-kashirshchini-poruynuvali-a-selyan-vivezli-v-inshu-oblast

- Білоус І. Чужина, що стала рідною. ТОВ «Агро-Овен». Газета “Агро-Інформ” від 1 грудня 2001 року.

- Директива НКВД СССР № 122 об организации направления в ссылку членов семей оуновцев и повстанцев. 31 марта 1944 г. // ГА РФ. Ф. P-9401. Оп. 12. Д. 207. Т. 2. 1944 г. Л. 21—22. Типографский экз. Опубл.: Сборник законодательных и нормативных актов о репрессиях и реабилитации жертв политических репрессий. Курск, 1999.

- Mass deportations from the West of Ukraine in 1939-1940. URL:https://deportation.org.ua/mass-deportations-from-the-west-of-ukraine-in-1939-1940/

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update