Vladyslav H.: Taiga, how did the deportations of 1949 differ from those of 1941, and why did they happen again?

Taiga K.: The deportations repeated due to a change in circumstances. While World War II hostilities on Latvian soil ended in 1944, a widespread national partisan movement continued to gain momentum. A lot of people were fighting in the forests and resisted conscription into either the German or Soviet armies. As a result, many people were deported for supporting this national partisan movement by supplying food and shelter.

In this second wave of deportation, 44,271 people were expelled from Latvia — primarily women, the elderly, and children. This time, if there was a man in the family, he was sent to a settlement site, although such families were rare. The 1949 deportations had two main objectives. First, families supporting the national partisans were evicted as a preventive measure to quell the movement. Second, the aim was collectivization — forcing Latvian peasants into Soviet collective farms. Many Latvian farmers were reluctant to join these farms, but those who owned 20–30 hectares of land were automatically classified as “kulaks” and deported. All their property, including agricultural machinery, land, and livestock, was confiscated for collective farms. In total, 2–3% of the Latvian population was deported.

This pattern mirrors what the Soviet authorities had previously done in Ukraine during the 1930s, when over 200,000 peasants were labeled “kulaks” and deported for refusing to join collective farms. Later, in 1947, the Soviets carried out Operation West and evicted supporters of UPA. Hence, we see the same totalitarian practices and non-human system of the communist regime wherever it takes hold.

Vladyslav H.: I assume the Soviet authorities never anticipated that deportees would return home had it not been for Stalin’s death. Did children who grew up in the camps struggle with self-identification? Was it challenging for them to speak Latvian afterward?

Evita F.: That’s what I’m working on right now. We are studying the testimonies of eyewitnesses from the deportations of 1941 and 1949. According to these accounts, older individuals never lost hope of returning home, even though they were uncertain when or how that might happen. At the same time, the younger generation, who were either born or raised in the resettlement camps, had resigned themselves to their circumstances. We have video testimonies, even from mothers and daughters, who had divergent perspectives on the same deportation experience. The older generation made an effort to retain their Latvian heritage and names, while the younger generation sometimes adapted their names to Russian spellings, for example, ‘Tamara’ instead of the Latvian ‘Mara’ or ‘Mari’.

The situation varied from case to case. The younger deportees did not always teach their children Latvian, often busy due to work commitments. However, if a grandmother was present, the third generation of the family, she might take the lead to teach the children the national language. Sometimes, returning from deportation created problems with language adaptation. We know of one instance where a family opted to enroll their children in a Russian-language school in Latvia because it was easier for the child.

Vladyslav H.: This is very useful information as we investigate the current deportations of Ukrainian children by Russian invaders and their efforts to erase national identities through imposed Russification. Taiga, could you elaborate on the loss of identity experienced by children in the special settlements? Were there children who grew up unable to speak or understand Latvian well enough to continue their education in Latvia?

Taiga K.: While there may have been some complications, I think national identity was generally preserved within the family unit. In the 1950s, upon returning to Latvia, these children could enroll in one of the many Latvian schools still remaining in rural areas. Educational challenges often arose due to material constraints; many children, especially boys, worked on collective farms to support their families, leaving little time to study.

In fact, national identity was maintained through family bonds and interactions with other Latvians. However, preserving one’s culture sometimes came at a high cost — for instance, singing Latvian songs at a resettlement camp could result in transfer to a prison or labor camp.

Evita F.: We started collecting video testimonies in 1996 and continue to do so today. My colleagues shared an interesting story of two deported sisters: one returned to Latvia, while the other remained in the resettlement area. Cases vary; sometimes, people returned to their home country many years later but struggled to find employment or housing and ultimately went back. We have poignant accounts of families torn apart by deportations, but such stories do exist.

Vladyslav H.: Evita, could you tell us about the archive of evidence concerning Soviet deportations from Latvia?

Evita F.: We have amassed a collection of 2,262 video testimonies and continue to record more. These include accounts from victims evicted between 1941 and 1949, witnesses of the deportations, and individuals who managed to evade deportation but still recall those terrible events.

Vladyslav H.: Taiga, in your opinion, how do the Soviet deportations from Latvia compare with the contemporary deportations of Ukrainians?

Taiga K.: The objectives behind these crimes are probably the same — to crush the spirit and resistance of the people. In 1941, Latvians were deported to the Krasnoyarsk region, and in 1949, more were sent to Tomsk, Omsk, and Amur regions, located 5-6 thousand kilometers away from Latvia. The intention was for the deportees to stay there forever without the right to return.

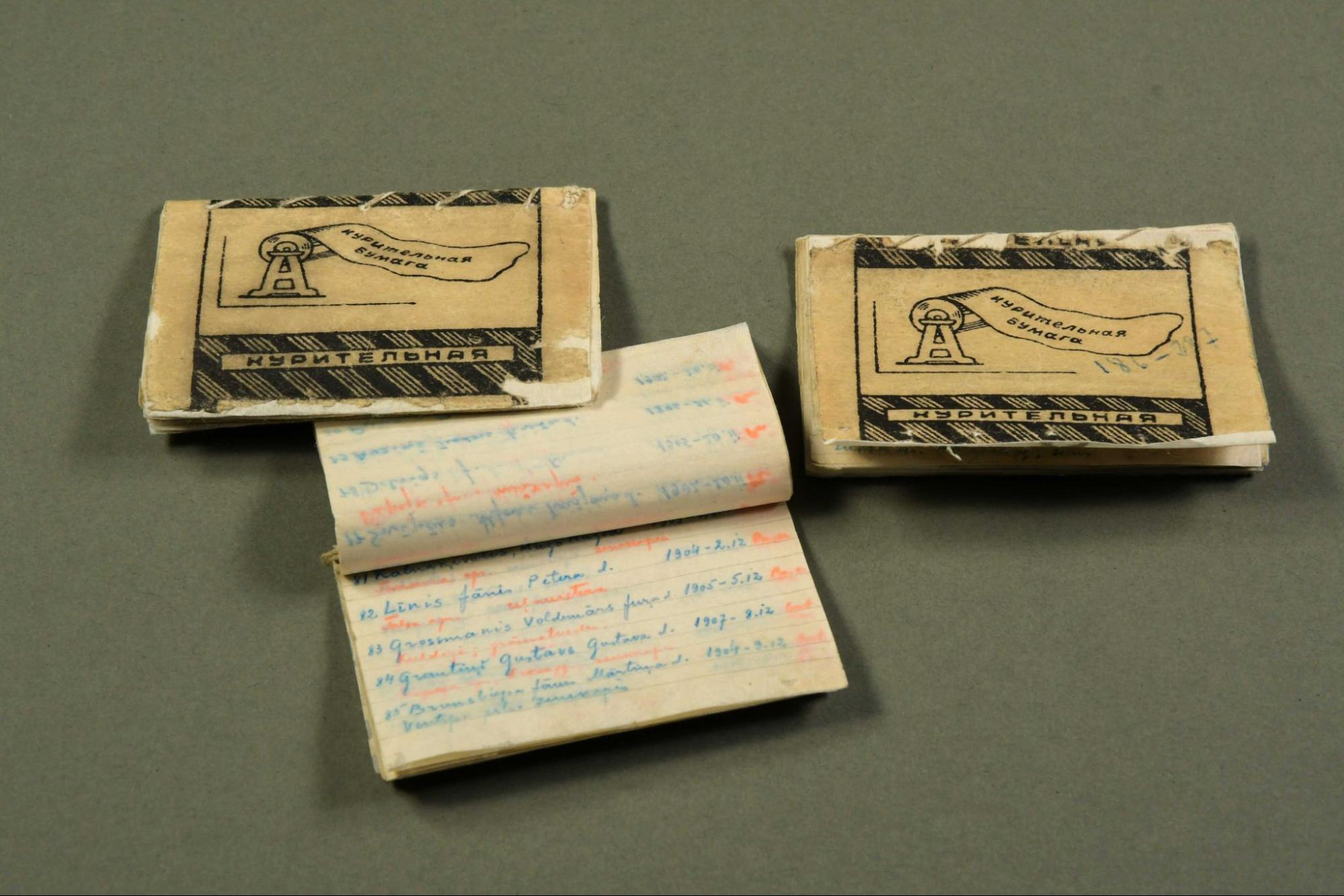

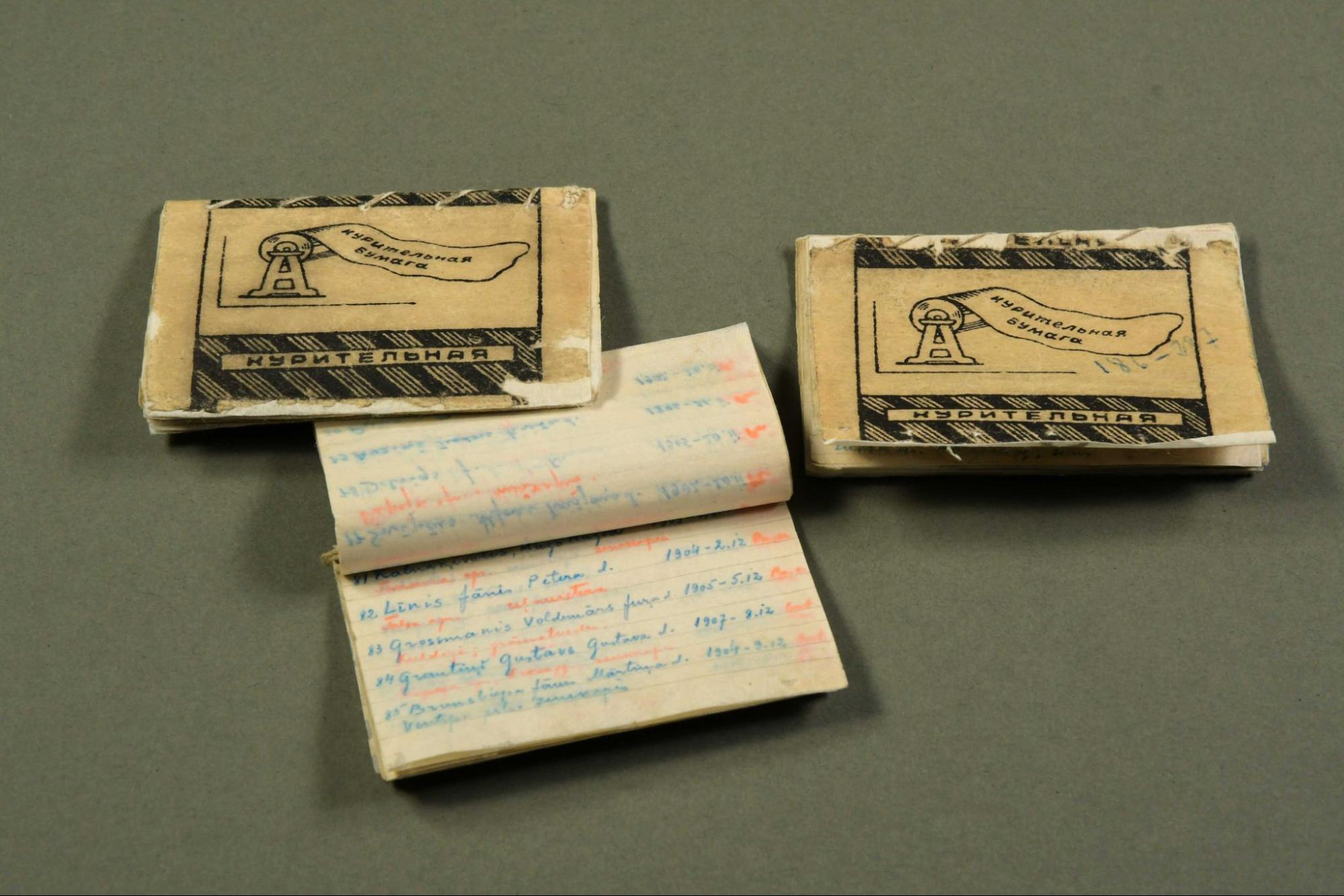

Our museum keeps the notebooks of Doctor Janis Schneider, a surgeon who was deported from Latvia and continued his work in a Viatlag camp. From August 1941 to June 1942, he recorded the deaths of over 400 men who were deported in 1941.

Modern Russia appears to be pursuing a similar agenda, as we find evidence of Ukrainians being deported to Siberia and the Far East regions of the Russian Federation, including Kamchatka. It is imperative to condemn and halt this criminal activity to ensure that deportations never repeat in Latvia or Ukraine.