Encyclopedia

Deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944

The Soviet occupation regime not only deported people from Ukraine based on their economic status, the process known as “dekulakization”, but also targeted specific ethnic groups. This article focuses on the forced removal of the indigenous people residing in Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula — the Crimean Tatars (qirimli).

The deportation efforts in Crimea by the Soviet Union were marked by the communist regime’s attempts to forcibly alter the ethnic composition of the population. According to the ruling elite of the USSR, the qirimli were considered a “harmful element of society” and were therefore to be expelled from their homeland as punishment for their unwillingness to “contribute to the prosperous future of the USSR’.” In the 1940s, during the onset of the German-Soviet war, the Nazis occupied the Crimean Peninsula. The Soviet leadership held the Crimean Tatars responsible for this occupation, accusing them of deserting the Soviet army and collaborating with the Nazi authorities. Additionally, even those qirimli who had served in the Soviet army were stigmatized, initially due to their ethnicity, and subsequently because of the Soviet military’s failures.

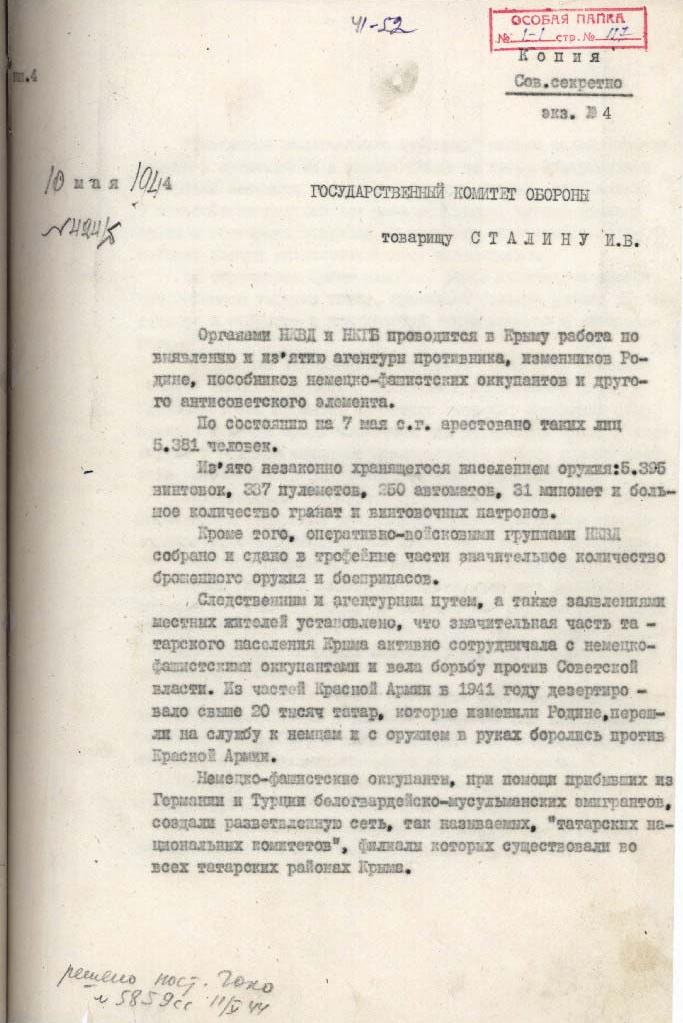

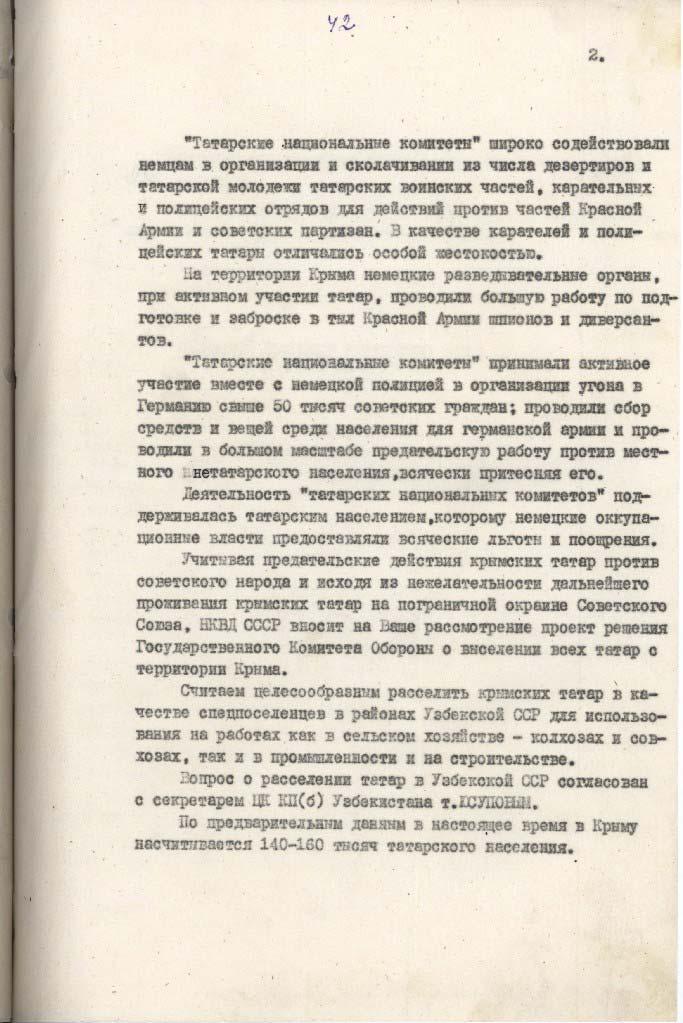

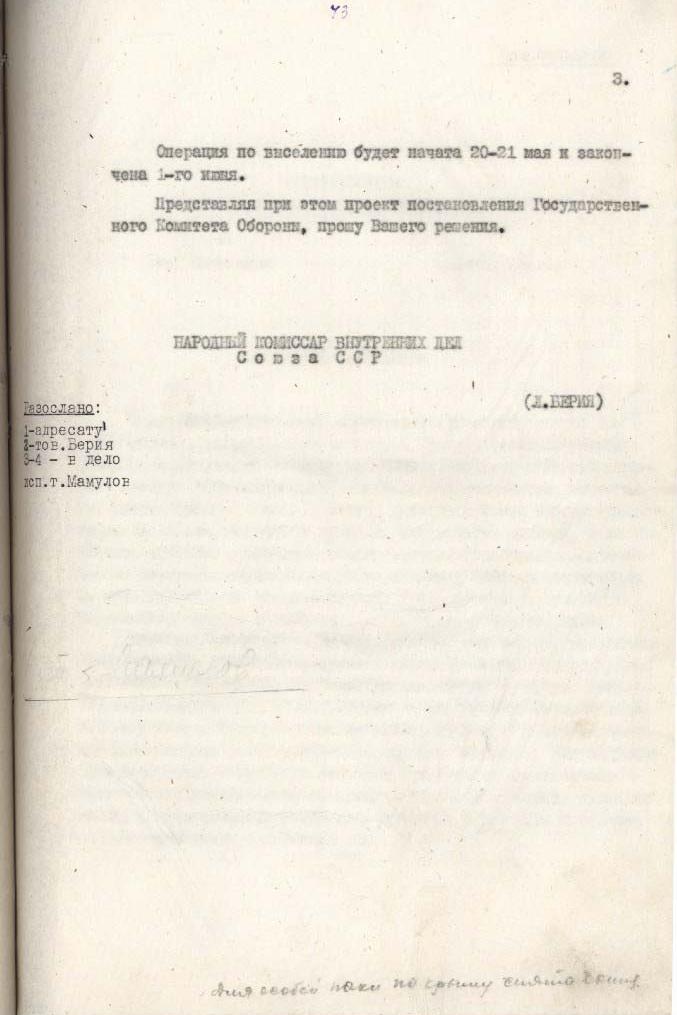

On April 22, in a report to Lavrentiy Beria, Crimean Tatars were accused of mass desertion [1]. Later, on May 10, Lavrenty Beria reiterated these accusations in a memo to Stalin, using phrases such as “The treasonous actions of the Crimean Tatars against the Soviet people” and even more disparagingly, “The Crimean Tatars have no desire to live on the outskirts of the Soviet Union [i.e., the Crimean Peninsula]” [2]. In this memo, Beria also proposed deporting the entire qirimli population to Uzbekistan [3]. Naturally, his justifications for such a proposal were fabrications designed to expel an entire ethnic group that opposed the communist regime. Ukrainian historians characterize the reasons for the deportation of the Crimean Tatars as a large-scale repressive action against communities whose individual members were accused by the Soviet authorities of collaborating with the German occupiers [4, p. 3].

DON’T MISS IT

Subscribe for our news and update

The qirimli themselves describe this as the culmination of an eternal conflict between the Crimean Tatars and the Soviet (Russian) authorities. They view World War II as a pretext for the final “cleansing” of Crimea of its indigenous people [5, с. 110].

On May 11, 1944, the State Defense Committee of the USSR issued a decree No. 5859 managing the deportation of Crimean Tatars from the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic to the Uzbek SSR. The Soviet authorities meticulously prepared for the deportation. In addition to ideological justifications, they mobilized significant resources: 5,000 operatives from the NKVD and NKGB arrived in Crimea, while an additional 20,000 soldiers and officers from the NKVD internal troops participated in the covert operation [6]. According to other sources, up to 32,000 Soviet soldiers, including NKVD officers and other security forces, were involved in the deportation process [7].

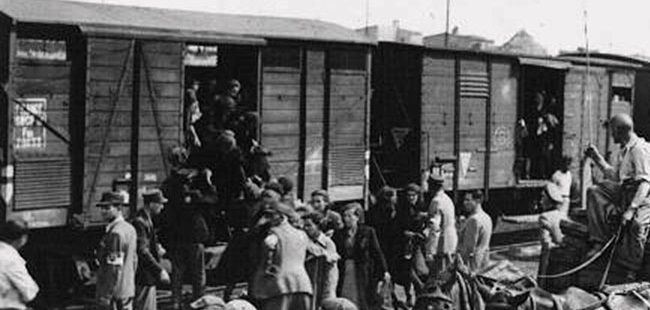

The official deportation of Crimean Tatars began on May 18, 1944, although in some areas of the peninsula, it started on the evening of May 17. Dilaver Ennanov, who was a young victim of this forcible deportation, described it this way: “On the evening of May 17, 1944, numerous trucks appeared in Simferopol. Concurrently, many, many soldiers appeared in the city. We, as young boys, roamed the streets trying to count them but kept losing track. Could we have imagined their purpose? A curfew was still in effect, so my mother and I went to bed early. Suddenly, in the middle of the night, there was a loud knock on the door. I woke up to see an officer angrily reading something from a paper to my mother, who had just opened the door. Two soldiers stood before her. They hurried us, saying we had 10 minutes to gather our belongings […] We were led out of the house and into the yard, where our neighbours, also Crimean Tatars, sat with their belongings in the rain, surrounded by internal troops. We stayed with them until dawn. Cars arrived, and we were taken to the outskirts of the city, to the railway station […] I remember being placed in double carriage No. 44. Amid tears, moans, and screams, the train began to move. As we crossed the border of Crimea, everyone on the train sang a song. They sang and wept, looking back” [6].

Crimean Tatars are forcibly loaded into a freight wagon for deportation. Source: Ukrainian Institute of National Memory. https://uinp.gov.ua/ . [7]

Crimean Tatars in soviet freight wagons preparing for deportation. Photo source: https://zmina.info/. [8]

Usniye Cholpan, a Crimean Tatar, also recalled the harrowing morning of May 18, 1944 in her testimony: “In the early morning, Soviet soldiers burst into our house: ‘Get ready! You traitors are being evicted.’ Where? Why? Confused and frightened, not understanding what was happening, the young children Urmus, Leniye, Seitjelil, and Sundus cried. First, I grabbed the Quran, then the frying pan and jezve. When we were led out, everyone around us was crying and screaming.” Along with others, they were herded into train cars and taken to the Suren station, a railway station in the Bakhchisaray district of Crimea.

On May 18, 1944, Beria, the People’s Commissar of the NKVD of the USSR, informed Stalin and Molotov that 90,000 Crimean Tatars were ready to be loaded onto trains. The following day, a special contingent of 165,000 people was assembled from across the peninsula, of whom 136,412 were deported [9, 500].

Soviet soldiers forcibly loaded people into railroad trains. Usniye traveled with her children and nephews. Her grandparents and a young child died en route, as did many other qirimli. There was no opportunity to bury the deceased. During brief stops, children were allowed out of the cars to fetch water. Eventually, the qirimli were transported to Uzbekistan. Shortly thereafter, like many other deportees, they contracted malaria and dysentery. Usniye became seriously ill, and her family feared she wouldn’t survive [11].

Usniye Cholpan, archive of Gulnara Bekirova. Source: Radio Liberty.[11]

On May 20, 1944, Deputy People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs of the USSR, I. Serov, and Deputy People’s Commissar for State Security of the USSR, B. Kobulov, summarized the results of the operation in a report to the top party and state leadership. They stated that the deportation of Crimean Tatars was completed at 16:00, and 180,000 people had been resettled. Over the course of three days, the punitive authorities dispatched more than 70 railroad trains from the peninsula, each containing 50 cars packed with qirimli [9, 501]. On May 21 and 29, 1944, additional resolutions were passed, mandating new resettlements of Crimean Tatars to the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and the Gorky, Ivanovo, Kostroma, Molotov, and Sverdlovsk regions of the RSFSR [6].

Zera Batalova, a qirimli, detailed the horrendous conditions of the deportation and forced placement in freight cars: “On May 18, 1944, my mother Nuriye, her parents Medzhit and Fatma, sisters Biyan and Emina, as well as my mother’s cousin and daughter, were deported. My brother Enver was at war at the time and only began searching for his relatives in 1946… Everyone, except for my mother’s eldest sister, ended up in the Urals, specifically in the Komi Perm Autonomous Okrug. My mother was fortunate to be with her family, but her sister Biyan was sent to Uzbekistan…

My mother recounted that our journey to the Urals took at least three weeks. The train only stopped in forests and sometimes remained stationary for several days, but passengers were not allowed to leave the wagons. Consequently, they lost track of time during the prolonged journey. Upon arrival in the Urals, people were famished. They resorted to gnawing on tree bark. When they learned that potatoes had been planted in the area the previous year, they searched for and consumed last year’s frozen potatoes” [12].

Zera Batalova’s grandfather Medzhit Haniyev, grandmother Fatma, uncle Enver, aunt Biyan and mother Nuriye, 1929. Source: ICTV Facts. [12].

Deported qirimli were designated as special settlers and were evicted for life. The Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, titled “On Criminal Liability for Escape from Places of Compulsory Permanent Settlement of People Expelled to Remote Areas of the Soviet Union During the Patriotic War,” dated November 26, 1948, imposed a severe penalty for escaping from a special settlement — 20 years of hard labor [6]. This explains why the qirimli did not return to Crimea.

The regime of special settlements for repressed peoples from Crimea was officially abolished only by the decrees of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet of March 27, 1956 (for Crimean Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians) and April 28, 1956 (for Crimean Tatars) [13, p. 79]. Although these decrees lifted administrative supervision over the special settlers from Crimea, they did not provide any right to compensation for lost property during the eviction and barred them from returning. This policy was formally in effect until 1974, but effectively lasted until 1989 [6].

The entire process of deportating the Crimean Tatars, involving the forced mass expulsion of an entire ethnic group and the subsequent prevention of survivors from returning to Crimea, has been classified as genocide against the qirimli. Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the UN General Assembly resolution 260 (III) of December 9, 1948 [12], defines an act of genocide as one committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, any national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. The Soviet authorities committed direct genocide against the qirimli in 1944, demonstrating their criminal methods of enforcing submission to the communist dictatorship — either through forcible subjugation or the destruction of entire communities. The demographic consequences of this act are still felt to this day.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Sources & References:

- Депортація кримськотатарського народу. Історія геноциду. URL:https://crimea.suspilne.media/ua/articles/71

- Історична довідка про депортацію кримськотатарського народу 1944 року. URL:https://lublin.mfa.gov.ua/news/5514-istorichna-dovidka-pro-deportaciju-krimsykotatarsykogo-narodu-1944-roku

- Депортация крымских татар. Документы. URL: https://bessmertnybarak.ru/article/deportatsiya_krymskikh_tatar/

- Крим в умовах суспільно-політичних трансформацій (1940‒2015). Збірник документів і матеріалів. 2-е вид. / Упоряд.: О. Г. Бажан (керівник), О. В. Бажан, С. М. Блащук, Г. В. Боряк, С. І. Власенко, H. В. Маковська. Відп. ред. В. А. Смолій. НАН України. Інститут історії України; Центральний державний архів громадських об’єднань України; Центральний державний архів вищих органів влади та управління України; Галузевий державний архів Служби безпеки України. ‒ К.: TOB “Видавництво “Кліо”, 2016.

- Ніколаєць Ю. Кримські татари у роки Другої світової війни: сучасний науковий дискурс. Наукові записки Інституту політичних і етнонаціональних досліджень ім. І.Ф. Кураса НАН України. – 2019 / 3-4 (99-100) .

- Пагіря О. Згадати все. Депортація кримських татар у травні 1944 року URL:https://artefact.org.ua/history/zgadaty-vse-deportatsiya-krymskyh-tatar-u-travni-1944-roku.html

- 1944 – почалася депортація кримських татар. Історичний календар. Травень 18. Український інститут національної пам’яті. URL:https://uinp.gov.ua/istorychnyy-kalendar/traven/18/1944-pochalasya-deportaciya-krymskyh-tatar

- Як радянська влада депортувала кримських татар. URL:https://zmina.info/articles/deportacijia_krimskih_tatar-2/

- Сталинские депортации: 1928–1953 / Под общ. ред. акад. А. Н. Яковлева; Сост. Н. Л. Поболь, П. М. Полян. – М.: Международный Фонд “Демократия”; Материк, 2005. – (Россия. ХХ век. Документы).

- Постановление ГОКО № 5859сс от 11 мая 1944 г. О крымских татарах // ГАРФ. Ф. Р.— 9401. Оп. 2. Д. 65. Л. 44-48; Принудительное переселение крымских татар. Путь к реабилитации: Материалы и док.— М.: Аквариус, 2015.

- Гульнара Бекірова. «Помирали цілими сім’ями»: спогади очевидців про депортацію кримських татар. URL:https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/spohady-pro-deportatsiyu-krym-tatfry/31260956.html

- Тетяна Забожко. Діти помирали від переляку: як відбувалася депортація кримських татар. URL:https://fakty.com.ua/ua/ukraine/20210518-dity-pomyraly-vid-perelyaku-yak-vidbuvalasya-deportatsiya-krymskyh-tatar/

- Кримські татари. 1944–1994 рр. Статті, документи, свідчення очевидців. К.: «Рідний край», 1995.

- Конвенція про запобігання злочину геноциду і покарання за нього. Ухвалена резолюцією 260 (III) Генеральної Асамблеї ООН від 9 грудня 1948 року. URL:https://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/conventions/genocide.shtml

- Депортація кримських татар у 1944. Інфографіка. URL:https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-other_news/2018926-deportacia-krimskih-tatar-v-1944-infografika.html

- Депортація кримських татар у цифрах (інфографіка). URL: https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/27743517.html