Deportations of Pontian Greeks in 1942 and 1944: Examining the Causes, Scale, and Locations

Find out how Soviet authorities uprooted over 30,000 Greeks from their historical homelands in 1942 and 1944 without any justifiable reason.

One of the peoples who fell victim to the communist crimes of the Soviet Union, namely forced deportation from their permanent place of residence in the Far East, were ethnic Koreans. It should be noted that this ethnic group had lived in the Far East long before the arrival of Soviet power. Korean migrants settled in the Far East in several stages.

Project Erased histories is supported by the European Union under the House of Europe programme.

The first stage took place in the mid-19th century, between 1863 and 1884. One of the first official reports of this was the permission to resettle Koreans from the military governor of the Primorsky Krai, when 14 Korean families consisting of 65 people secretly crossed into Russian territory in January 1864 and founded the first Korean village 15 kilometres from the Novgorod post — Tizinh, which in 1865 was renamed the village of Rezanovo. Thus began Korean immigration to the Far East of Russia [1].

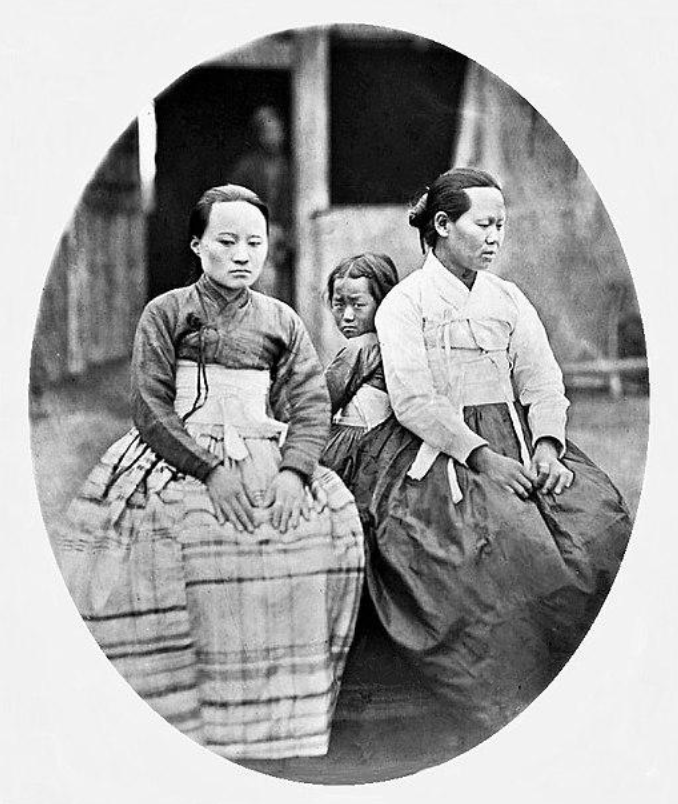

Korean women in the Far East, 1860-1870s. Photo source: Vladimir Vasilyevich Lanin.

During the second stage, from 1884 to 1905, an additional factor stimulating the growth of the Korean population was the position of the Amur Governor-General, S. M. Dukhovsky, who was in favour of using Korean labour in the Amur region. They were granted land plots for development and cultivation, but on condition that they accepted Russian citizenship. In the interests of the state, Dukhovsky considered it necessary to swear in the first category of Koreans without delay in order to improve their material situation by granting them such privileges and, at the same time, to generate sympathy for Russia on the part of Korea. S. M. Dukhovsky’s policy on the Korean question was continued by his successor as Governor-General of the Amur Region, N. I. Grodekov (1898–1902). During his tenure, the Korean population was divided into specific categories and their rights were regulated. Thus, in 1891, all Koreans residing in Russia were divided into three categories:

Also, on Grodekov’s initiative, the “Regulations on Chinese and Korean subjects in the Amur Region” were developed, according to which all Koreans of the first category who remained without oath were accepted into Russian citizenship, and it was promised that Koreans of the second category who had lived in the Ussuri region for at least five years would also be accepted into Russian citizenship; Koreans of the third category were allowed to settle along the Iman, Khor, Kye and Amur rivers [1]. As a result of this policy, the Korean population in the region increased almost fourfold.

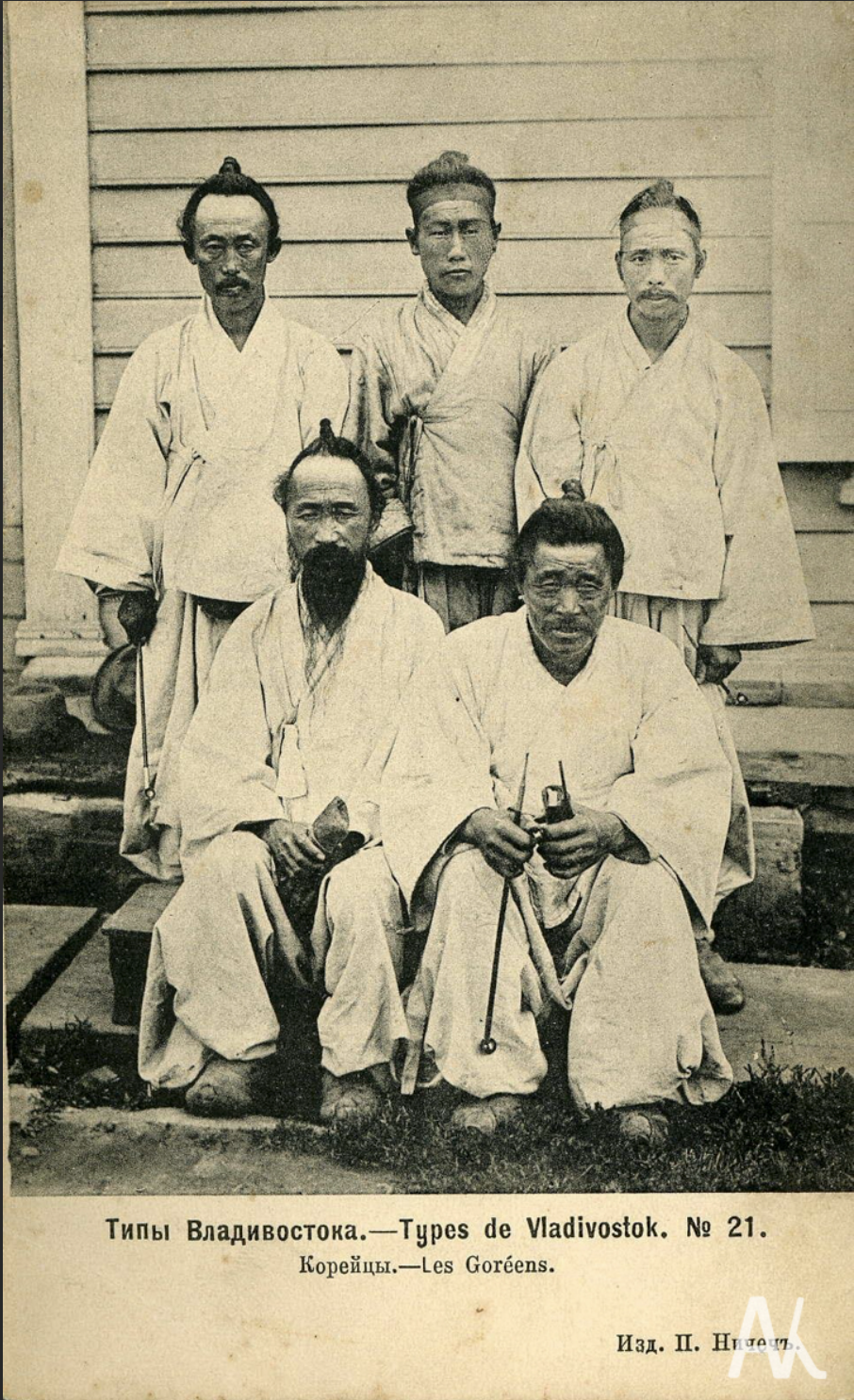

A group of Koreans in Vladivostok. Early 20th century.

The third stage of resettlement took place between 1904 and 1917 and was most closely associated with the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 and the subsequent establishment of a Japanese protectorate over Korea, which led to an increase in Korean emigration to Manchuria and the Russian Far East. A large number of Koreans tried to escape the pressure exerted by the Japanese authorities on ethnic Koreans at that time, which led to one of the largest resettlements of ethnic Koreans in the Far East. Thus, the number of officially registered Koreans in the Amur Region grew: in 1911 — 62,529 people; in 1912 — 64,309; in 1915 — 72,600; in 1917 — 84,678 [1].

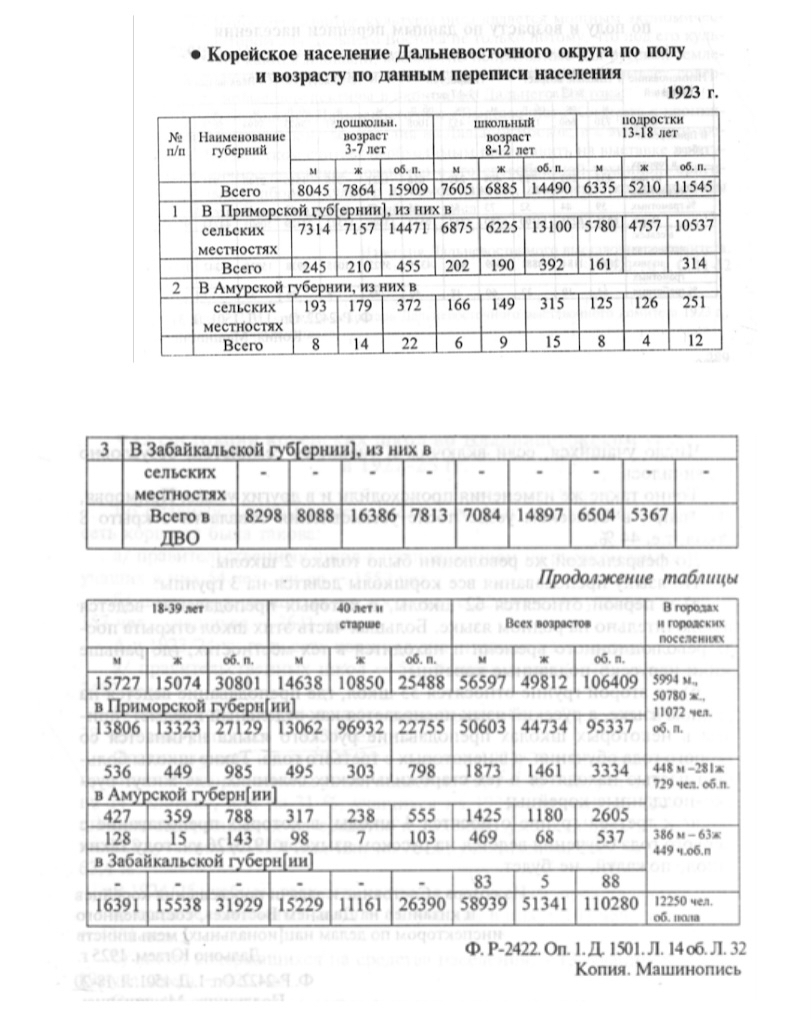

Ethnic Korean population of the Far Eastern District by gender and age according to the 1923 census [3]

When Japanese troops invaded China on 7 July 1937, Korea was part of the Japanese Empire. The Soviet authorities also suspected Korean immigrants living in the USSR of “aiding the enemy and espionage” and accused them of working for Japanese intelligence. Their physical resemblance to the Japanese did not help the Koreans either. In addition, former citizens of the pro-Japanese state of Manchukuo (Manchurian state) and former employees of the Chinese Eastern Railway were also subjected to repression. In other words, anyone who, in the opinion of the Soviet special services, was associated with Japan was subject to arrest and deportation [4].

The Soviet authorities tried to remove ethnic Koreans from the Far East in a tried and tested but criminal manner – by deporting them from these territories, thus destroying them as one of the indigenous peoples of these lands. Just before the deportation began, the Soviet authorities adopted Decision No. P51/734 of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) on 21 August 1937 [5], which stated that in order to stop alleged “Japanese espionage” by the Korean population of the Far East, the following measures should be taken:

Renowned researcher of the deportation of Koreans during the Soviet period, Professor German Kim, describes the deportation process as follows: “Ethnic Koreans were given a minimum amount of time to gather their belongings, after which they were forced to board special trains for resettlement (with their names, place of boarding and time of departure indicated). Each carriage carried 5–6 families (25–30 people). The “human” carriages were actually freight cars, poorly equipped with double bunks and a stove. During registration before deportation, Koreans had their passports, hunting and shooting weapons confiscated. These trains travelled from Primorye to their destinations in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for 30–40 days [6].

Another well-known researcher, Professor of Architecture Mykola Kim, recalls these events: “In the autumn of 1937, we received an order to quickly prepare for a long journey. Rumours spread that we were being taken to warmer climes. We sold our winter clothes and began to gather our belongings and food. On 30 October, my family was loaded into freight cars with two-storey bunks for 20 people: women, children, old people – all together. We travelled, of course, through Siberia and arrived at our destination in Kazakhstan (Ush-Tobe station). We arrived only on 24 November. We were on the road for 25 (!) days in the freezing November Siberian cold! Many, especially children and the elderly, did not reach their destination and died on the way. The dead were hastily buried at the first half-stations and the journey continued, without anyone knowing why or where they were going. My father had a stroke. The rest also fell ill… This was the state policy against Koreans.” [7]

Zinaida Yurievna Anahovich recalls cases of starvation and death during the weeks-long deportation:

“My family and I were transported for three months from the Far East and brought to the Golodna Steppe station in Uzbekistan. We were dropped off in a completely barren steppe. My family – my parents and four children – were deported from the Primorsky Krai, the village of Zarichchia in the Mikhailivsky district, a border area. What were we accused of? Enemy of the people, traitor to the motherland – on the basis of our nationality. There were many immigrants from Korea living in the Primorsky Krai, who had moved there after the conclusion of the Korean-Japanese treaty of 1876 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. I come from a family of immigrants. My parents moved to Russia, and then I was born in the Soviet Union. My maiden name is Khegai… We arrived with four children and our parents. We were the only family in that train that survived the journey. My parents told me that all the other families had lost children, sometimes not just one but two or three. Back then, all Korean families had many children… There was sabotage on the road, an accident – they tried to destroy us Koreans as best they could. On purpose. At every station, they buried someone – parents, children, old people. People died. It is a difficult, dark and very sad story…” [8].

In total, on the basis of Joint Resolution No. 1428-326ss of the Council of People’s Commissars and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) “On the eviction of the Korean population from the border areas of the Far Eastern Territory” dated 21 August 1937, signed by Stalin and Molotov (Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars in 1930–1941) [9], 172,000 ethnic Koreans were deported from the border areas of the Far East to the desert and uninhabited areas of Kazakhstan and Central Asia [10].

A Korean family in the fields of Central Asia

The consequences of the deportation of ethnic Koreans from the Far East were dire — approximately 11,000 people died during transport in freight trains due to harsh and unfavourable conditions. Upon arrival, Koreans faced new tragic challenges to their lives — cold and hungry steppes, where there was an acute shortage of housing and land for farming. Even in the new territories, due to fears and suspicions of espionage, the communist authorities continued to isolate Koreans and keep them under the control of the NKVD.

At the same time, in the Far East, the Soviet authorities destroyed the historical memory of these peoples — numerous Korean national districts, village councils, schools, institutes, newspapers and theatres were liquidated, scattered or destroyed after the deportation. This story is a prime example of dozens of other deportation processes carried out by the Soviet authorities, destroying entire peoples [11].

Find out how Soviet authorities uprooted over 30,000 Greeks from their historical homelands in 1942 and 1944 without any justifiable reason.

The 1949 deportations of Pontian Greeks were a dark chapter in history. Learn how they faced hardships, lost homes, and were denied justice.

What led to the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944? Discover the Soviet Union’s motives and the lasting impact on the qirimly community.

and we will send you the latest news