Deportations from the Baltic Countries in 1940-1941

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

Editorials

In this revealing interview, Elmar Gams, a researcher specializing in the Soviet deportations from Estonia, provides insights into the dark history of deportations and their long-lasting effects. From discussing the commemoration of the first deportation in 1941 to examining the motives behind the Soviet occupation and the resurgence of deportations in 1949, Gams highlights the systematic destruction of Estonian society and the deliberate suppression of its independence. He also delves into the experiences of deported children in special settlements, the challenges they faced upon returning to Estonia, and the importance of recording and preserving the testimonies of survivors. The interview serves as a poignant reminder of the crimes committed during this period and the ongoing implications that continue to shape Estonia’s historical memory.

Vladyslav Havrylov: Your research is centered around the Soviet deportations from Estonia and the project you started, Kogu me Lugu, portal of oral history what doing this investigation in a base of Estonian Institute of Historical Memory is all about it. Please tell us about the commemoration of the first deportation on June 14, 1941.

Elmar Gams: June 14 is officially considered a Day of Mourning in Estonia. Also this day, with a different name, but in its meaning also dedicated to deportations is remembered in Latvia and Lithuania, because on June 14, 1941 deportations were carried out simultaneously from these three countries. Particularly from Estonia about 10 thousand people were deported, most of them, around 2/3 were women and children. This was different from the deportations after WWII (in 1949, for example). Women and children were particularly sent ;to take part in the resettlement in Kirovska Oblast of the RSFSR and Novosibirska Oblast — the part that later became Tomsk Oblast. At the same time, men were not transported alongside their families but were instead subjected to individual deportations. The women and children were grouped together in one section of the train, while the men were relegated to a separate compartment. Subsequently, during the journey to their place of exile, the men were forcibly detached from the train and transferred to the brutal confines of the Gulag labor camps.

That is, men were not even sent for deportation to a special settlement, but precisely to the Gulag camps, where some were sentenced to death, others died of the terrible conditions. This is what distinguishes the deportations of 1941 from later deportations.

The women, in turn, found it much more difficult to survive without a husband, without a father, even in the subsequent post-war deportation of 1949. In 1949 they were already evicting whole families, villages, but together it gave them a chance of survival. And those people who were deported in 1941, for them it was the most difficult…

Vladyslav H. When the Soviet occupants came to the territory of Estonia in 1939, there were arrests and single deportations of political elite, in particular President Konstantin Päts and Commander-in-chief of the army Johan Laidoner. Was it an attempt to suppress pockets of independence in the country?

Elmar G. I think it is a very interesting topic in the sense that the Russian Federation has never acknowledged that the Baltic states were occupied by the Soviet Union, they still say it was the states’ “voluntary” wish to become part of the Soviet Union. The Soviet troops arrived in 1939, established their military bases here, then in the summer of 1940, they issued an ultimatum” either you let in more Red Army units or we begin military operations against you. The leaders of the Baltic nations initially yielded to the ultimatum, but subsequently arranged protests involving the same individuals who had advocated for a government transformation. They conducted elections in July that allowed Communist bloc members to participate while excluding independent candidates without party affiliations. When new parliaments were formed in all 3 republics, they announced their wish to become members of the Soviet Union.

If this is all, as the Russian federation says, voluntary, then the question arises, then why was it necessary to destroy all these people when it happened? President Päts, Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces, Lydoner? And not only them, but also many generals, officers, and big businessmen. Or Jan Tennyson, who was head of state in the 1920s? He was arrested for absurd “counter-revolutionary” activities. Here it is clear that if you want to destroy traces of statehood, you are deliberately going to destroy the people associated with the foundation of that statehood and the foundations of society. From this it is clear that incorporation into the USSR was not voluntary in essence.

With Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, we can observe the same tactic in Russian-occupied territory of the country. The Russian occupiers act purposefully to identify ATO veterans, unruly mayors, teachers, public figures and so on. The logic of action remains exactly the same as it was then.

Subscribe for our news and update

Vladyslav H. Indeed, these examples show very clearly this attempt to destroy the independence of any of Russia’s occupied countries. Following the end of World War II, the Baltic states experienced a cessation of forced deportations. However, these deportations were reignited in March 1949 with the implementation of Operation Surf. What were the reasons behind this resurgence?

Elmar G. I think that already in 1941, the Soviet authorities “managed” to eliminate from the country some people who were connected to the political, social component of Estonia. And if we look at the history of Estonian SSR, Latvian SSR or Lithuanian SSR, published from the early 1950s and republished continuously till the end of the Soviet occupation, they explain the Soviet vision of these events. Also in the 1970s and 80s, in books like these, the deportations of both 1941 and 1949 were explained as a “class struggle”, distorting the events in a way that the Soviet Union was “forced” to do so. In the same way Russia is now trying to show its invasion of Ukraine as a “forced measure”.

In Estonia, Latvia there were 2 such large deportations, these were June 14, 1941 and March 25, 1949. In Lithuania, the situation was similar to that of Western Ukraine. People actively resisted Soviet power with weapons, and a greater number of individuals were subsequently deported from Lithuania.

On March 25, 1949, about 20,000 people were deported from Estonia, while the original plan was to deport 22,000. Here already whole families, sometimes even whole villages were deported and they were mostly sent to the same place of settlement, though in “better” conditions than in 1941. But here we have to keep in mind that such people were deported permanently, i.e. forever.

In the case of Estonia, on March 25, 1949, the so-called “kulaks” were deported. They were heavily taxed, some were able to pay the taxes, some not, but people were deported anyway. And some of the people who were family members of those who had been condemned to the Gulag or convicted by the Soviet authorities after the re-entry into Estonia in 1944, for allegedly collaborating with the German occupiers, were not particularly aware of the subject of this collaboration, and were immediately deported.

Vladyslav H. You said they were deported for eternity. We are talking about the regime of special settlements, which were formed on the territory of Siberia, Tomsk Oblast, yes? It is intriguing to note that in studying contemporary Ukrainian deportations, we observe attempts to indoctrinate deported Ukrainian children with Russian ideology. It seems that Russians anticipate these children will be unable to return home and will be subjected to ongoing propaganda. In your opinion, do you think the children who were deported from Estonia grew up in these special settlements and were largely unfamiliar with the Estonian language and culture due to such circumstances?

Elmar G. If we are talking about the deportations of 1949, they were already different from the deportations of the kulaks from Ukraine in particular in the 1930s. Here people were not deported, so to speak, to a clean field, but to special settlements. When people were brought to Novosibirsk Oblast, for example, the heads of collective farms in the same district or several districts came and chose “workers” on the spot. Afterwards, they were placed in some buildings, with people to whom they paid rent and worked on the collective farm. Of course, even in this case, it was difficult to survive when you were deported to an unfamiliar area 5,000 kilometers away from home.

As for the propaganda you mentioned, it seems to me that people who were deported in 1941 suffered most here, because back then they were often sent away with only their mothers. If a parent, a mother died, her children were sent to an orphanage and there they probably fell more under this influence in terms of language too. As for the children from deported families in 1949, it was a little easier there. Although they went to a Russian school, the upbringing of the family prevailed and the identity was largely preserved.

The problem with language difficulty came when people deported as children returned to Estonia in the 1960s, 1970s. In this case it was difficult for them to continue their studies in Estonian. They knew and remembered the language at some level, but the spelling, the grammar — that was difficult, and only few managed to enter higher education institutions.

Also, based on my interviews with survivors of the deportations, there was certainly propaganda, but those who lived with their families, there was a certain filter to it.

Vladyslav H. We know that the current Prime Minister of Estonia, Kaija Kallas, comes from a family of deportees. Her grandmother was deported and her mother grew up in deportation. Do you know more about this story?

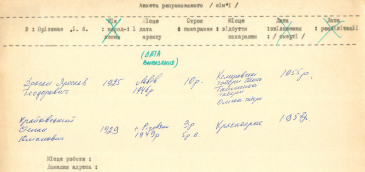

Elmar G. In Estonia, our Estonian Institute of Historical Memory is running a database of the victims of communism in Estonia from 1940 to 1991. This database is open to everyone, anyone can browse on memoriaal.ee and there is information about both those deported and those who were sent to the Gulag.

And in this database, I found information about Kaja Kallas’ mother, named Kristi, and there is information that she was deported from South Estonia to Khakassia (South Siberia) when she was 6 months old, together with her mother and grandmother. She stayed there until she was 10 years old, when she returned. The reason was that Kaija Kallas’ grandfather was “condemned” in 1945 and sent to the Gulag.

Vladyslav H. Your project Kogu me Lugu deals specifically with interviewing victims of deportations. What is the best way to record, document and show people these horrific, yet important, testimonies?

Elmar G. I think it is better to communicate with living witnesses, to recreate a picture of what happened first-hand. The more such testimonies we have, the more complete this picture of the deportation events will be, as we do not know when we will be able to get to the Russian archives, where there is evidence of decision-making about these crimes.

Our oral history portal also tries to capture the oral testimonies of deportees who are still alive, those who were sent to the Gulag. Of course, it is important to work with archives, with documents, but we should also not forget about the living, human component of these stories, how these people felt, how they were treated.

Vladyslav H. Now, we are trying to prove the deportations of Ukrainians is a genocide. It seems to me that if the International Criminal Court had existed before, the deportations from the Baltic states could have fallen into this category, don’t you think?

Elmar G. I think we should be clear about genocide here, that despite all the tragic events it is exactly destruction on national, ethnic or religious grounds. In this regard, what happened in Estonia is a crime without time limit, against humanity, and the fear of punishment for their perpetration should haunt those who committed this until the end of life.

On the other hand, when the Russian Federation declared itself the successor of the USSR it meant that they have not only accepted what is convenient from the past period but are also responsible for all those crimes that were committed in the Soviet period. Russia hasn’t been punished for those past crimes. And all this permissiveness and impunity is creating new crimes. In its time, the Nazi regime of Germany was condemned, but the Soviet crimes haunt us and are still being committed today, especially after February 24, 2022, this past is even more evoked and, unfortunately, is our present.

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

In an illuminating dialogue, Director of Ukraine’s Archive of National Remembrance Ihor Kulyk and historian Vladyslav Havrylov engage in a thought-provoking discussion about Ukraine's national memory surrounding forcible deportations.

The piece reveals Russia's use of deportation as a tool for demographic solutions, with a focus on Ukrainian children and church complicity.

and we will send you the latest news