Deportations of Pontian Greeks in 1942 and 1944: Examining the Causes, Scale, and Locations

Find out how Soviet authorities uprooted over 30,000 Greeks from their historical homelands in 1942 and 1944 without any justifiable reason.

The period of Stalinist terror was marked by numerous acts of mass deportation, which became a central tool of Soviet policy on the “national question”. One of the lesser-known but no less tragic episodes in this history is the forced expulsion of the Pontic Greeks. Between 1942 and 1944, more than 30,000 members of the Greek minority were deported from Ukraine and the Azov Sea coast to Kazakhstan and other remote, uninhabited regions of the USSR. Despite the active phase of World War II, the Soviet leadership did not stop ethnic cleansing, which shows the systematic nature of the persecution of even such small communities as the Greeks.

Project Erased histories is supported by the European Union under the House of Europe programme.

The end of the war did not halt these repressive measures. On the contrary, in 1949, amid post-war reconstruction, the authorities deported over 37,000 ethnic Greeks from the Black Sea and Azov regions. Ethnic cleansing became part of a broader Soviet project to construct the idealized “Soviet man”, which unfolded alongside the rebuilding of cities and the displacement of indigenous populations. The recurrence of repressions in 1938, 1942, 1944, and 1949 points to a deliberate and long-term Soviet policy aimed at eradicating the Greek presence in southeastern Ukraine.

This article discusses the background, causes and consequences of the three waves of deportations of Pontic Greeks, their course and living conditions in places of exile.

The Greek ethnic group lived on the territory of Ukraine from the 8th century BC. Black Sea Greek colonies such as Olbia, Tyra and Chersonesos were important trade and cultural centres. They remained so throughout Ukraine’s history as port cities and points of contact with other cultures and ethnic groups through merchants and sailors. During the Soviet occupation of Ukraine in the 1920s, the Soviet leadership embarked on a policy of “indigenisation”. The policy aimed to involve indigenous peoples in the development of the state, as there was inequality between Russian and non-Russian peoples. As a result, Greek schools were opened, a Greek department was established at the Mariupol Pedagogical Technical School, the newspaper Kolekhtivisty was published, and Greek libraries and cultural centres were established. On 23 February 1932, the first State Greek Theatre in the USSR was opened in Mariupol. Thus, Greek education and culture in the Ukrainian SSR developed significantly, but was suppressed in the following years of Stalin’s terror.

Source: https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%82#/media/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Pontus.png

The Greeks, like any other people, fell victim to the dispossession policy carried out in the USSR in the late 1920s and early 1930s, aimed at eliminating the “kulaks” (wealthy peasants) as a class. Traditionally, the Greek population was engaged in trade and agriculture, owned land and property, and therefore it was not in their interest to transfer all this to state ownership. In addition, the Greeks insisted on retaining their Greek citizenship and did not want to obtain a Soviet one. The resistance of Greek peasants and merchants to the policies of the Soviet Union gave the authorities a formal pretext for mass arrests and subsequent deportations.

During 1931, nearly one-tenth of the Greek population of Ukraine was dispossessed and deported to Kazakhstan. During 1931–1932, the loss of labour resources in Greek villages amounted to 10–20% of their population.[1]

Between 1935 and 1937, the Soviet Union’s nationalities policy entered a new and brutal phase, largely driven by the implementation of agricultural collectivisation. This campaign, far less successful than Soviet propaganda claimed, unfolded in difficult conditions — particularly in the USSR’s densely populated, multi-ethnic regions. Resistance to collectivisation was met with severe punishment, and the government introduced systematic repressions not only against individuals and social groups but also against entire ethnic communities. One stark example is NKVD Directive No. 50215, issued on 11 December 1937, which initiated the so-called “Greek Operation.”

The People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR, M. Yezhov, justified the need for punitive measures against members of the Greek minority by claiming they had created an extensive network of nationalist, espionage, sabotage, and subversive organisations aimed at undermining the Soviet regime.

Local NKVD departments received orders from the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, Izrail Leplevsky, to carry out mass arrests of ethnic Greeks. A large-scale operation was launched, resulting in the arrest of more than 20,000 Greeks in southern Ukraine. For comparison, according to the 1939 census, the total number of Greeks in the USSR was 286,444.[2] The so-called “Greek Operation” did not end with these initial repressions — instead, it intensified with the outbreak of World War II.

On 4 April 1942, Lavrentiy Beria signed Directive No. 157, instructing the NKVD administrations in the Krasnodar Region and Kerch to “immediately begin cleansing Novorossiysk, Temryuk, and Kerch, the settlements of the Taman Peninsula, as well as the city of Tuapse, of anti-Soviet, foreign, and suspicious elements…” Among those targeted were ethnic Germans, Romanians, Crimean Tatars, and Greeks.

At the end of May 1942, the State Defense Committee (DKO) adopted Resolution No. 1828ss, which ordered: “In addition to the above-mentioned locations, within two weeks, deport in the same manner persons deemed dangerous to the state from Armavir, Maykop, Kropotkin, Lebedinskaya, Petrovskaya, Krymskaya, Timashevskaya, Kushchovskaya, Defanovskaya stanitsas, as well as from the Rostov region and areas adjacent to Krasnodar Krai — including Azov, Bataysk, and Aleksandrovsk…”.

Among the main reasons for the deportation of Pontic Greeks was the Soviet Union’s attempt to artificially construct the ideal Soviet citizen — one without national or ethno-cultural identity. This ideological pursuit resulted in mass arrests, unfounded accusations, and harsh sentences. As a consequence, the Soviet authorities actively sought to eliminate so-called “unreliable elements”: individuals who refused to renounce their national, cultural, and ethnic roots.

The second reason for the forced deportation of ethnic Greeks in the Soviet Union was the issue of citizenship. Around 20% of Greeks living in Crimea held Greek citizenship, either exclusively or alongside Soviet citizenship. Under the 1937 Soviet laws, they were classified as foreign nationals, which made them subject to deportation — either beyond the borders of the USSR or deep into its interior — as part of a broader policy aimed at their complete “assimilation”.

Another cause was rooted in the traditions of the GULAG system. The Soviet state systematically exploited prisoners from forced labour camps as a source of cheap labour. This practice intensified during World War II, when the demand for workers in the military-industrial sector grew exponentially. Many of the Greeks who were arrested and deported to the Far East of the USSR—where numerous military facilities had also been relocated — were intended to serve as a readily available labour force for these wartime industries.

Additionally, the reason for the forced deportations of the Greek population was Joseph Stalin’s personal revenge for his failures in Greece. On the eve of World War II, the leader aimed to create a springboard for the spread of communism in Greece. The plan failed due to the restoration of the monarchy by Metaxas on 4 August 1936 in Greece.[3]

By May 1942, 1,402 ethnic Greeks had been deported from the Krasnodar Krai and Rostov Oblast. In addition, Greeks were expelled from Armenia, Azerbaijan, the Black Sea coast of Georgia, and Abkhazia. The total number of people forcibly deported at that time was 16,376.[4]

The gathering took several hours. Some managed to pick vegetables from their gardens for the journey, while others only had time to gather the necessary clothing.

In 1942, the route ran to Kazakhstan or the Krasnoyarsk region. Approximately 100–150 families were sent to Kyrgyzstan.[5] The time spent on the road varied. Greeks from Baku travelled for 58 days to the Trudovik collective farm in the Petropavlovsk region. The journey from Sochi to the Karaganda region took 67 days. During that time, they had no opportunity to take a shower and arrived at their destination sick.[6]

When the deportation trains stopped to wait for the next connection, the Greeks were forced to spend the night under the open sky. There was a constant shortage of water, food, and firewood, so they often had to exchange clothing and jewellery for provisions from local villagers near the temporary stops.

In April 1942, Greeks were deported from Tuapse and other locations in the Krasnodar region in ordinary passenger carriages. This was likely intended as a signal to German pilots, who might avoid bombing civilian trains. However, once the trains left the combat zone, the deportees were transferred into freight cars.

Simela Kocheli, who survived deportation at the age of 12, recalled the journey, “Transfer in Stalingrad. Already in passenger carriages. The Germans are bombing. We’re leaving. We’re already travelling through Kazakhstan. We stop at a half-station. Several people get off, including me and my uncle Kolia. We drink fresh water from a puddle”.[7]

During the 1942 deportations, Greeks were sent to Kazakhstan (Alma-Ata, Karaganda, and Pavlodar regions) and the Krasnoyarsk Territory. Several families were also relocated to Mozdok (North Ossetia), Buynaksk (Dagestan), and various villages in the Stavropol Territory. Special settlements were established for the Greeks, but in reality, these were little more than dugouts in the steppe, marked only by serial numbers. Some deportees were housed in former prisoner barracks. Having left behind all their property and possessions, the Greeks were forced to start their lives anew in places with no food, infrastructure, or even basic living conditions.

In 1944, a second wave of deportations took place. In May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria justified the deportation of Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Greeks and Armenians from Crimea in a report to Stalin. He accused the Tatars of harming the Soviet partisan movement in the Nazi-occupied peninsula and supporting the fascist occupation regime. Regarding the Bulgarians, Greeks and Armenians, Beria wrote: “The current population of Crimea includes 12,075 Bulgarians, 14,300 Greeks and 9,919 Armenians… The Greek population lives in most regions of Crimea. A significant part of the Greeks, especially in coastal cities, took up trade and small industry with the arrival of the occupiers. The German authorities assisted the Greeks in trade, transportation of goods, etc. The NKVD considers it expedient to carry out the expulsion of all Bulgarians, Greeks and Armenians from the territory of Crimea.”.[8]

This note shows that there were no cases of active collaboration with the Nazis among the Greeks, nor were there any grounds for such suspicions. In addition, Greeks made up a significant part of the Soviet partisans operating on the peninsula and undermining the activities of the Nazi occupation forces. However, this fact was ignored during the deportation, and the Greeks were accused of “trade and small industry”. According to Beria, the Greeks “deserved” deportation for sewing clothes and selling fish at the market.

On 18 August 1944, the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the Kazakh SSR, M. K. Bogdanov reported to the Special Settlements Department of the NKVD of the USSR that “Bulgarians, Greeks, Armenians, Gypsies, Tatars, and Karaites who had been deported from the Crimean ASSR in July 1944 on ethnic grounds had arrived in the Guryevsk region of the Kazakh SSR”.[9] Throughout 1944, they were also deported by the NKVD to special settlements in the Molotov, Sverdlovsk, and Kemerovo regions, as well as the Bashkir ASSR. In total, 37,455 families were affected, including 16,006 Greeks, 9,821 Armenians, and 12,628 Bulgarians.[10]

While in 1942 Greeks were transported partly in passenger cars, by 1944 there was no longer a threat from German aircraft. Trains deporting people from Crimea carried up to 2,000 individuals each. For example, the last two trains—composed of approximately 90% Greeks—transported 2,256 and 1,950 people, respectively.[11]

Pavlo Angelidi, a deported Greek from the Azov region, recalls, “In September 1944, the train arrived in Stalinsk. People were placed in tents. There was taiga all around, and they were cutting down trees because they needed to build barracks urgently. Winter was just around the corner, and the temperatures in those parts reached 50 degrees below zero. They knocked together some barracks, and families were separated by sheets or sacks.”[12]

If deportations during World War II could be manipulative justified by collaboration with the Nazi occupiers, then four years after its end, the pretext was even more far-fetched:

By a completely secret decision dated 17 May 1949 (Protocol No. 69 of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks), the Central Committee instructed the Ministry of State Security of the USSR to deport Greeks in order to “cleanse the Black Sea coast of unreliable elements.”[13]

The resolution stated that the Ministry of State Security of the USSR was obliged to resettle all Greek citizens and former Greek citizens who already had Soviet citizenship and lived on the Black Sea coast, in Georgia and Azerbaijan, to the South Kazakhstan and Dzhambul regions of the Kazakh SSR. The evacuees were allowed to take personal belongings and food up to 1,000 kg per family with them. The USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs was obliged to ensure the convoy, transportation and supervision of the evacuees, as well as their employment in their new places of residence.

The number of Greek families to be deported was also specified. It was planned to deport 6,000 Greek families (21,600 people) to the Dzhambul region and 1,500 families (5,400 people) to South Kazakhstan.[14]

Greek deportations in the USSR – Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deportation_of_the_Soviet_Greeks#/media/File:Greek_deportations_in_the_USSR.jpg

The main task of the military in the first stage was to remove people from their homes. The next step was to transport them to railway stations.

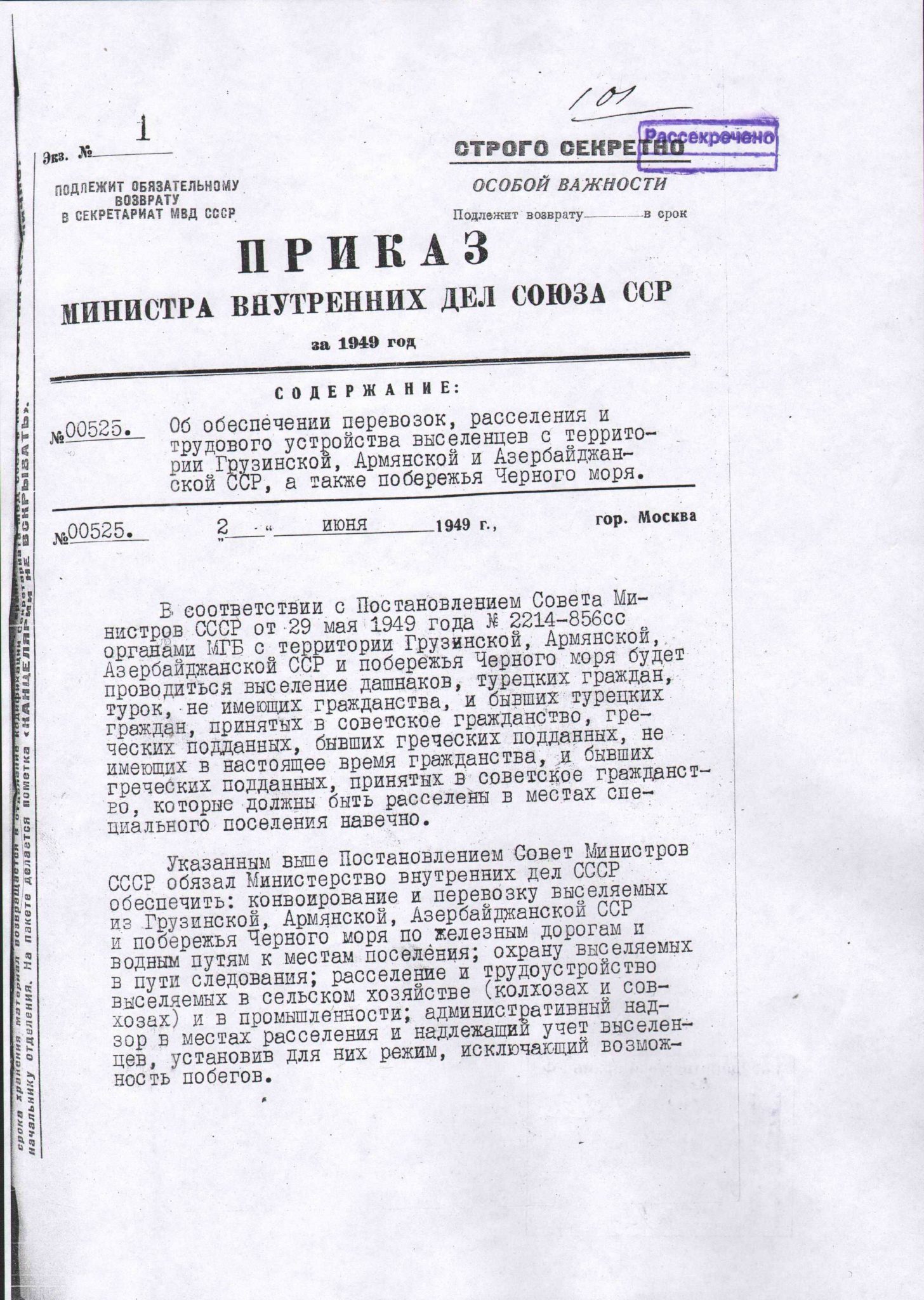

To this end, Decree No. 00525 of 2 June 1949 was issued, titled “On ensuring the transport, resettlement and employment of evacuees from the territory of the Georgian, Armenian and Azerbaijani SSRs, as well as the Black Sea coast”. It was ordered “for the period of the eviction to take the necessary measures to strengthen the protection of the state border in the areas of eviction” and to ensure “proper public order in the cities and other settlements from which the eviction will take place”.

Decree No. 00525 of 2 June 1949 – Source: https://evnreport.com/magazine-issues/exile-to-siberia/

On the night of 12 to 13 June 1949, all Greek villages in Abkhazia were surrounded by troops of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. An officer with a pistol and two soldiers with automatic rifles entered each yard. The officer announced the expulsion of the family, then checked the lists to make sure everyone was present. The Greeks were given two hours to gather their personal belongings and food. By noon, they were taken out of the mountainous areas and loaded onto trucks, three families per truck, and by evening they were taken to railway stations in Sukhumi (Abkhazia). If the transport was delayed, soldiers with automatic weapons guarded the deportees as if they were criminals.

The Greeks were placed in 60-tonne freight cars that had previously been used to transport livestock. Some cars had double-decker wooden beds. Children and young people were placed on the upper decks, while the elderly and sick were placed on the lower decks. People were worried about how they would survive without food and water in the heat, especially with children and the sick without medicine or medical care. Although the authorities officially provided doctors for each train, medical care was poor and people died on the way. The carriages were terribly stuffy and there were no toilets.

Christophoros Keshanidi, a Pontic Greek, recorded his memories of his fellow villagers’ journey: “At first, we were transported in locked carriages. Soon, the children and the sick began to die from the unbearable conditions. At stops and crossings, not far from the train, soldiers and our people dug pits, threw the dead into sacks, and covered them with earth. When we were delayed, the locomotive gave several short blasts. This meant that someone was being buried and the train was delayed. Soon we were covered in scabies and lice. We soaked rags in kerosene and wiped the necessary places, the lice died and we combed them out…”.[15]

On 14 June 1949, two trains carrying Greek deportees from Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia met at the Makhachkala station. The guards allowed the passengers to walk around and stretch their legs. Christo Tiftikidi, a native of Baku, got off the train with his lyre and began to play a Pontic melody. This is how the event was described by a witness, Christo’s brother, Nikolai Tiftikidi:

“The Pontiaks, provoked by the playing of the lyre, began to perform a group dance. It had everything: anger and despair, pain and joy — the emotions of people united by fate in this tragic hour, in one body and one soul. The dance awakened a blood brotherhood that had long slumbered in the hearts of Soviet Greeks. The thousand-year-old voices of their distant ancestors spoke within their souls. They danced with such enthusiasm, fury, and passion, as if trying to drown their grief in the dance, trample it into the ground, and express their contempt for the guards accompanying the train. The dance was as beautiful as the Parthenon and as monumental as a fresco.”[16]

Musicians with lyra – Source: https://pontianlyrics.gr/persons/person-details?personId=103

[17]Upon arrival, the Greeks signed a “consent” form for permanent settlement. Greek citizens had their passports confiscated and were issued special passports for deportees. According to various sources, in 1949, the Soviet authorities deported more than 37,108 Pontic Greeks.

In total, 26 echelons of deported ethnic Greeks were sent to Kazakhstan in 1949. Most of them were from Georgia (19 echelons).

The majority of Greeks were settled in the South Kazakhstan region (centred on the city of Shymkent). The main crop there was cotton, but apples and grapes were also grown, which reminded the Greeks a little of home. Many Greeks ended up in the Mirgalimsay lead mine, others in collective farms. Greeks from the Odesa and Izmail regions were deported to the Alma-Ata region. There they were also settled in collective farms.

The Greeks, accustomed to a subtropical climate, found it extremely difficult to survive winters with snow over 50 centimetres deep and prolonged frosts, when temperatures dropped to minus 51 degrees.

Christophoros Keshanidis, a deported Greek, recalled in his memoirs, “Only on market days, Sundays, in the district centre did we find out who had been sent where and who was no longer alive. Within three to five years, most of the children, the sick and the elderly died, including my father. He could not get used to the new, sharply continental climate, was nervous because of his powerless situation and the ruthless treatment, could not come to terms with the very bitter fate that had been prepared for us, fell seriously ill and died…”.[18]

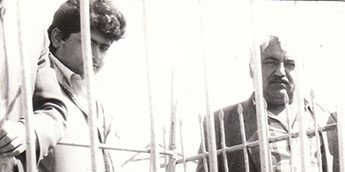

At the grave of deported Greek. Apostolos Simeonidi (died at the age of 34) Kokterek, Kazakhstan, 1990 – Source: https://www.pontosnews.gr/325582/ellada/oi-ellines-ton-parefxeinion-periochon/

There were other problems as well. Deported Greeks were forbidden to travel more than 25 kilometres from their settlement without permission and appropriate identity documents. Unauthorised departure from the special settlement was punishable by 20 years of hard labour. Those who tried to return illegally to their previous place of residence were arrested by the Soviet authorities and sentenced as criminals to five years in camps.[19]

In addition to such harsh punishment for wanting to live on the land of their ancestors, ethnic Greeks also lost their place of return. This was a symbolic loss, as the Soviet authorities changed the names of settlements and cities in order to erase memory. For example, this is how the USSR created the myth of “Russian Crimea”. By a decree of 18 May 1948, the settlements where the Greeks of Crimea lived were renamed. Thus, the village of Kapikhor became Morsky, Patrenit became Frunzensky, and Melas became Sanatorny.

From a letter by A. Parochidi, Greek ambassador to Moscow:

“On 13 June 1949, the entire Greek population was expelled from the Caucasus by force of arms, without being allowed to take any of their necessary belongings, and now the Greek people live in stables or completely homeless on the bare ground.

In general, the Greek people now have nothing, and they are forced to work, but they are not given any money, as special settlers, they are kept like cattle, and the whole people are sick, all the hospitals are overcrowded, and now, recently, doctors do not even admit them to hospitals, and the sick are dying without medical care.

The Greek people are eagerly awaiting, with great hope, that with the help of God and the Greek state, they will be able to return to their homeland.”[20]

Only after Stalin’s death in 1953 did rehabilitation take place and Greeks were granted the right to move freely within the republic.[21] On 27 March 1956, by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “On the removal of restrictions on the legal status of Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians and members of their families living in special settlements”, Greeks were granted the right to return unhindered to their former places of residence, including Crimea. However, the property confiscated from families during deportation was not returned to them. In fact, the Greeks had no homes to return to, as other people were living there.

Between 1965 and 1975, 15,000 Greeks emigrated from the Soviet Union and left for Greece. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, approximately 100,000 Greeks left the former USSR and also emigrated.[22] Unlike many other “punished” ethnic groups, Soviet Greeks were never officially rehabilitated under Soviet law.[23]

As of 2001, there were 91,500 ethnic Greeks living in Ukraine, mainly in Crimea.[24]

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Find out how Soviet authorities uprooted over 30,000 Greeks from their historical homelands in 1942 and 1944 without any justifiable reason.

A comprehensive look at Soviet deportations of Chechens and Ingush, from personal stories to international genocide recognition.

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

and we will send you the latest news