A Century of Deportations. How Russia Has Been Destroying Nations

Watch this video about how Moscow deported people during the Soviet Union and how its successor, modern Russia, continues implementing the same policy.

Encyclopedia

In the 19th century, during the Russo-Circassian War that spanned over a century, the Russian Empire carried out one of history’s most extensive genocides — the mass extermination and forced deportation of the Circassian people. Millions of peaceful civilians were killed, and an equal number were forcibly resettled. This tragedy ranks among the period’s most brutal, demonstrating the cruelty and relentlessness of the empire’s expansionist policies. This article will explore the circumstances, methods, and consequences of the Circassian deportation. Even today, 150 years later, Russia continues to use deportation as a military and political strategy, maintaining its intent to subjugate free peoples to affirm its own supremacy.

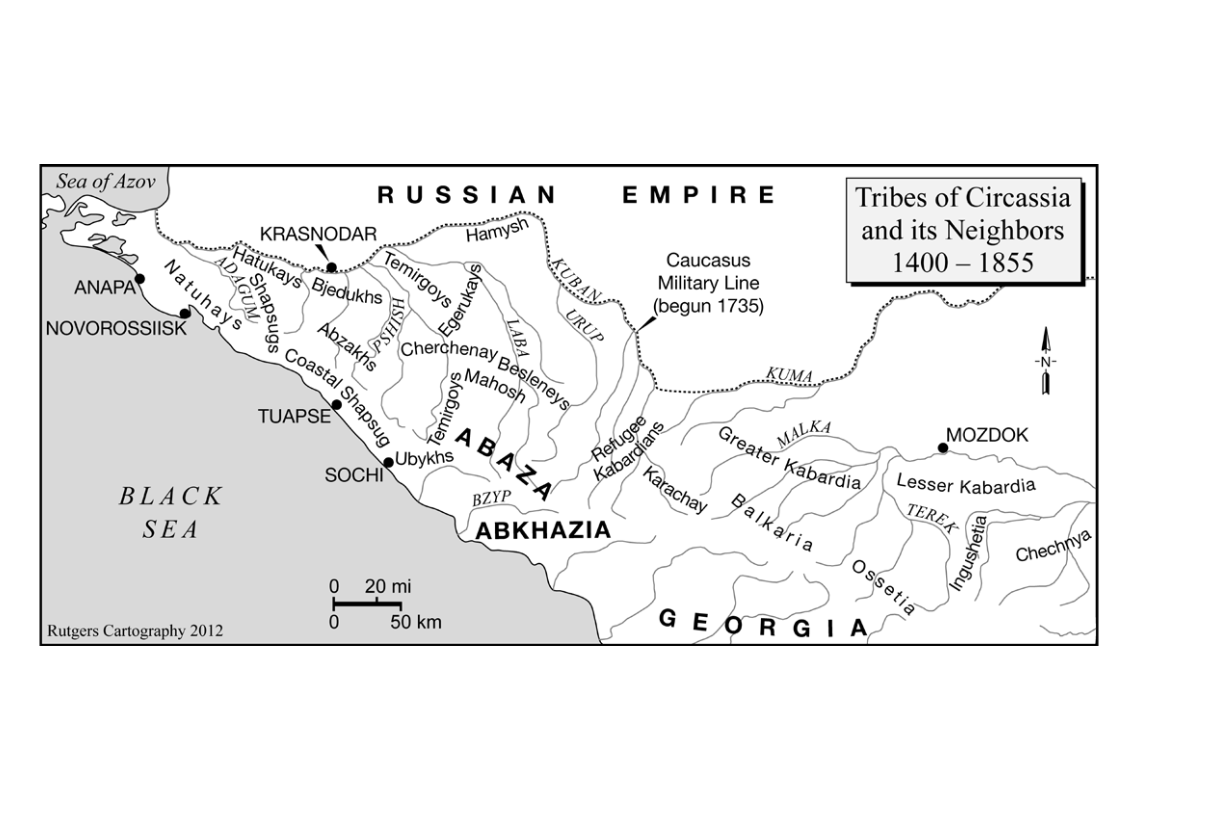

Now largely forgotten, but once vast and picturesque, Circassia inhabited the entire western and central North Caucasus — from the Black Sea in the west to the right bank of the Terek River in the east, and from the Main Caucasus Range in the south to the Kumyk steppes in the north. Its geographical location placed it at the crossroads of Western and Eastern cultures, bridging Christian and Muslim cultures.

The Circassians descend from the Hattians — a people who lived in Central Anatolia and settled on the northeastern coast of the Black Sea, between the modern cities of Sukhumi and Anapa, around 2000 BC [7].

The term “Adyghe” is a general self-designation that unites many independent peoples, including the Adyghe, Kabardians, Bzhedug, Temirgoy, Natukhai, Shapsug, Abadzekh, Besleney, Mahosh, Adamian, Ubykh, Zhaney, and Hakuchi.

The Black Sea coastline

The Circassians adhered to their own worldview, Adyghe Khabze, an unwritten code of ethics and laws emphasizing honor, hospitality, and mutual support. The aul (village) was central to their society, where a council of elders made decisions democratically and fostered strong social bonds and protection against external threats. These communities also had a keen sense of revenge, with hostility between auls and clans sometimes destroying entire communities across generations. Nonetheless, within the community, blood revenge was regulated by strict rules requiring the perpetrator to compensate the aggrieved party, who was then obliged to accept it.

Russia’s Century-Long War

The Caucasian War, considered the longest armed conflict in Russian history, lasted over 100 years.

The onset of Russian expansion into the Caucasus dates back to the 18th century, particularly from 1722, when Peter the Great launched the so-called Persian Campaign and marked the beginning of the systematic conquest of Dagestan, or the North-Eastern Caucasus.

The region’s large-scale expansion commenced with the establishment of the Mozdok fortress in 1763 and the construction of Russian fortifications along the Mozdok-Azov line. These developments encroached upon the territories of Caucasian polities and were perceived by the peoples of the North Caucasus as aggressive acts by the Russian Empire aiming to subjugate the entire region [10]. This was the start of the deliberate resistance of the Caucasian peoples against Russian interference.

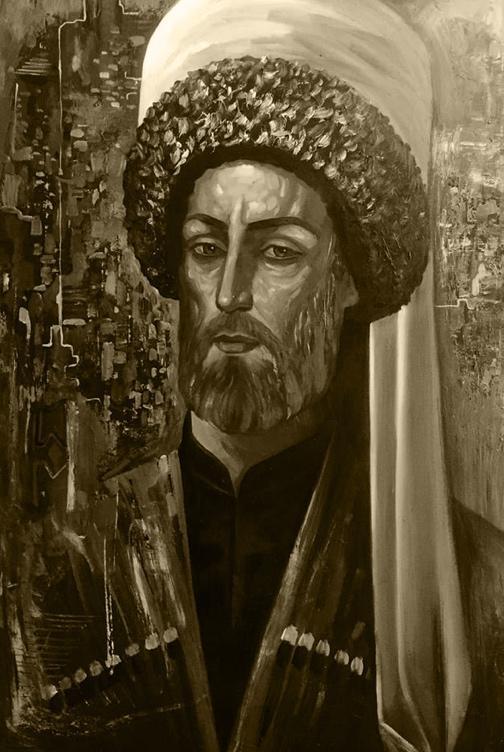

Sheikh Mansur, a military, religious, and political leader and the first Imam of the Caucasus, was the first to resist Russian colonization. He established the foundations of Muslim statehood in the region. In 1785, Sheikh united various Caucasian peoples and defeated Russian troops.

Sheikh Mansur

In reaction to Mansur’s successes, the Russian Empire adopted a policy of so-called pacification of the Caucasus, utilizing military force, constructing transportation routes, applying economic pressure, and carrying out deportations to subdue the free peoples of the region.

Sergey Bulgakov was the first Russian commander to employ genocidal tactics against the Caucasus peoples. In 1804, during an epidemic, possibly of malaria or typhus, in the North Caucasus, Bulgakov transformed the quarantine into an economic blockade, endangering the survival of the Kabardians, already weakened by hunger and disease.

Later, in 1810, under the pretense of offering protection, Bulgakov invaded Kabarda, destroying everything in his path and seizing livestock. According to Kabardian reports, he took thousands of livestock and burned nearly ten thousand houses and mosques. His actions led to famine, disease outbreaks, and a plague exacerbated by the lack of food and shelter, causing thousands of deaths [4, p. 31]. Bulgakov’s tactics in 1810 aimed not just at punishment or subjugation but at the complete annihilation of the Kabardians, leaving thousands homeless and facing starvation.

Russian military leaders believed in their superiority and civilizing mission. They justified the devastation of the Caucasus as a means to spread Christianity, peace, welfare, and prosperity in what they considered a barbaric and harsh region. Executions, often public, and forced starvation were deemed necessary for the progress and development of the empire and its peoples.

The Caucasus was destined to become an integral part of the Russian Empire, and the existence of any independent or semi-independent communities, irrespective of their religious or cultural characteristics, was deemed unacceptable.

The geopolitical situation facilitated the brutal tactics of Russian commanders. At the beginning of the 19th century, following negotiations with the Ottoman Empire and Persia, Russia legally acquired the territories of modern Georgia and the northern regions of Azerbaijan. This development led to a strategic reassessment of the significance of the North-Western and North-Eastern Caucasus, casting the Circassian peoples as an internal threat to Russian ambitions. The Paris Peace Congress of 1856, convened to address the aftermath of the Crimean War (1853-1856), inadvertently created conditions favorable for Russian expansion into the North Caucasus. The redeployment of the Crimean Army to the Black Sea coast significantly intensified military pressure on the Circassians.

Russian geographer and Major General Mikhail Veniukov described the war against the highlanders:

“The war was waged with unremitting, merciless severity. We advanced step by step, relentlessly eliminating the highlanders to the last man from any land that a soldier’s foot stepped upon. The highlanders’ auls were burned by the hundreds, as soon as the snow melted, but before the trees began to bud (in February-March). We trampled and destroyed their crops with horses. When we managed to capture the villagers off guard, we immediately sent them under escort to the Black Sea coast, and from there to Turkey. On occasion—to our troops’ credit, though rarely — atrocities bordering on barbarism occurred.”

“Assault on the aul of Gimry by Russian troops in 1832”, by F. Roubaud

Russian General Grigory von Zass, viewing the Circassians an inferior race, resorted to mass beheadings, displaying the severed heads on stakes near fortress walls. Moreover, he engaged in trading the skulls of the dead Circassians, which found buyers in Russia and Germany.

Military officer N. Lorer, who encountered Zass during the Caucasian War, described the horrific stench in the general’s office:

“Upon entering the general’s office, I was struck by an unbearably offensive odor, and Zass, laughing, ended our bewilderment by telling us that his men had undoubtedly placed a box of heads under his bed, and indeed he retrieved and showed us a large chest filled with heads that horrifically stared at us with glassy eyes. ‘Why are they here?’ I asked. ‘I boil and clean them, then send them to various anatomical cabinets and my academic friends in Berlin” [4, p. 55].

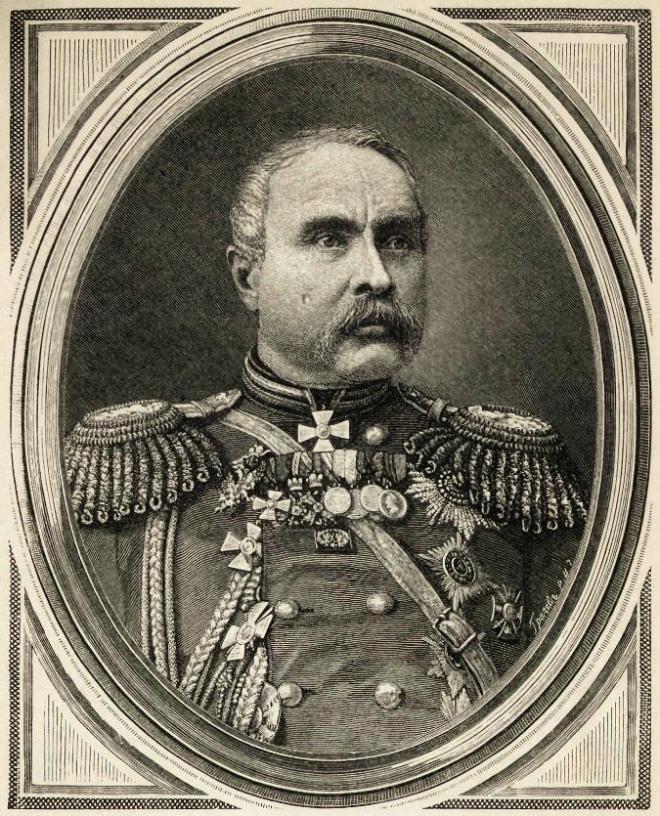

The peak of brutality was reached during General Yevdokimov’s campaign, where he was willing to sacrifice the lives of Circassian civilians to achieve his goals. Military units advanced along river valleys, coming across auls that the Circassians fled for the forests. The Russian forces razed villages, destroyed all available food, seized livestock, and then withdrew into the mountains. After a short pause, they resumed their advance up the valley, demolishing any makeshift shelters the Circassians had erected, repeating this cycle several times until Yevdokimov was convinced of the complete expulsion or demise of the local population.

General Nikolai Evdokimov

Despite warnings about the inevitable hardships and death that awaited those forced from their homes in the fall, Yevdokimov still compelled the highlanders to leave their land. He regarded these people as ones who “never offered open military resistance” and always followed Russian orders. Thus, he forcibly deported defenseless civilians, fully aware that most of them would likely perish.

“Highlanders Leaving the Aul at the Approach of Russian Troops,” P. Gruzinsky

Those seeking refuge in the mountains to escape Russian persecution faced a slow, inevitable death. French agent A. Fonville left descriptions of those conditions:

“We encountered several groups of people fleeing from the Russians. These poor people were in a pitiful state: clad in mere rags, guiding their small flocks of sheep—their sole sustenance—ahead of them; in silence, men, women, and children followed, leading a few emaciated horses that bore their household effects and whatever else they could carry.

These unfortunate inhabitants, ravaged by hunger and driven to desperation, resorted to eating leaves from trees. This extreme poverty led to outbreaks of typhus, which caused a horrendous death toll. Many unfortunate souls perished from hunger.” [4, p. 84]

Yevdokimov, adamant about the immediate completion of the deportation, disregarded the suffering and human losses that ensued.

Russian General Yuliy Neiman reported (1864):

“The auls and their supplies of bread and fruit have been incinerated; it can be reliably assumed that the population will either perish from hunger during the winter or approach our coastal points for deportation to Turkey” [9].

Subscribe for our news and update

Tragedy on the Seashore

Driven to the brink of hunger and overwhelmed by fear of the unknown, the Circassians were driven to the Black Sea coast, guarded by Russian troops. There was no shelter from the cold and blustery wind along the shore.

Fonville describes this moment in detail: “Often, entire groups of refugees succumbed to the cold or were buried by snowstorms, and we repeatedly saw their bloody trails on our path. Wolves and bears scavenged through the snow to reach the human remains” [4, p. 85].

The official departure points for the Circassians were designated as Novorossiysk, Anapa, Taman, and Sochi, but in reality, the entire northwestern coast became a massive gathering of refugees in the spring and summer of 1864. The first ships to Turkey from Trabzon set sail in early January, during the most unfavorable time for Black Sea navigation. Over 300 people were crammed onto each ship, far exceeding their intended capacity.

Circassians died en masse from typhus and smallpox. In the overcrowded ships, diseases spread at an astonishing rate, surpassing the speed of contagion on land.

![Circassian exile to the Ottoman Empire [3].](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/image2.png)

Circassian exile to the Ottoman Empire [3].

Here is how the events of 1863-1864 are described by Ivan Drozdov, a Russian army officer:

“At the end of February, the Psekup troops moved to the Marta River to oversee the expulsion of the highlanders, ready to forcibly evict them if necessary… Along the way, a remarkable sight unfolded: the scattered corpses of children, women, elderly people, torn apart, half-eaten by dogs; refugees exhausted by hunger and disease, barely lifting their feet from weakness, collapsed from exhaustion and, while still alive, fell victim to hungry dogs… Barely half of those who set out for Turkey reached their destination. Such a calamity, and on such a scale, has rarely befallen humanity; but it was only through horror that one could compel the belligerent savages to abandon their impregnable mountain gorges… Now in the mountains of the Kuban region, one may encounter a bear or a wolf, but no longer a highlander… The entire northwestern coast of the Black Sea was strewn with corpses and the deceased, amidst which small enclaves of the barely alive awaited their turn to be sent to Turkey.” [5]

The Black Sea coast was transformed into a vast cemetery.

The deportation of the Circassians and the armed confrontation with Russian troops in the mid-19th century resulted in significant human losses among the Circassian population.

Based on the data regarding the number of Circassians deported to Turkey in 1864, and considering estimates of mortality en route to the coast and from epidemics, it is estimated that between 726,000 and 907,500 people were deported from the mountainous areas [4, p. 91-92]

Researcher King believes that the Russians killed between 1 and 1.5 million Circassians and deported a similar number to the Ottoman Empire [3, p. 33].

![Consequences of Russian colonization — Ethnic population before and after [3]](https://deportation.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/image1.png)

Consequences of Russian colonization — Ethnic population before and after [3]

In 1929, academician Simon Janahia found a living witness to the genocide organized by the Russian occupiers in the Caucasus. His interviewee, Napsau Yabarkh Hansak, was 91 years old at the time. Here is what he recounted:

“For seven years, human bones lay scattered on the seashore. Crows made nests from men’s beards and women’s hair. For seven years, the sea washed human skulls ashore like watermelons, and I would not wish upon even an enemy to witness what I saw” [9].

On June 2, 1864, Yevdokimov announced that there were no Circassians left in the region and declared the day a holiday. The parade followed, and a gala dinner, during which Grand Duke Mikhail toasted the Kuban Cossacks and awarded them medals for their victory.

“Medal for the conquest of the Western Caucasus”

In a report to the Minister of War, Prince Mikhail stated: “The entire area of the northern slope to the west from the mouth of the Laba River and the southern slope from the mouth of the Kuban River has been cleared of hostile populations.” Emperor Alexander II endorsed the report with the resolution: “Thank God” [9].

The Russo-Caucasian War, lasting a century, ended, but at a tremendous cost to Russia. In the final years of the war, the Russian Empire committed significant financial and military resources to the conquest of the Caucasus. “In the last years of the war in the Caucasus, we had to maintain huge forces: 172 battalions of regular infantry, 13 battalions, and 7 hundred irregulars; 20 squadrons of dragoons, 52 regiments, 5 squadrons and 13 hundred irregular cavalry, 242 field guns. The annual expenses for maintaining these troops amounted to 30 million rubles,” recalled War Minister Dmitry Milyutin. By the war’s end, the Russian army in the Caucasus numbered 300,000 men, with annual casualties of around 30,000 men. One-sixth of the entire state revenue was allocated to the war effort [6].

The modern Circassian population worldwide is estimated to be between 4 and 6 million people, with only about 700,000 residing in the Russian Federation. This indicates the significant demographic changes caused by the genocide of the Circassian people [4, p. 92].

Today, Circassians seek the restoration of historical justice and the condemnation of the colonial policies of both the Russian Empire and contemporary Russia. In October 2006, the International Circassian Association appealed to the European Parliament to recognize the genocide of the Circassians in the 18th and 19th centuries, arguing that Russia’s actions were aimed at the eradication or forced expulsion of Circassians from their ancestral lands [2]. Georgia is the only country that unanimously recognized the Circassian genocide, doing so in 2010 [8].

Every year on May 21, the Circassian diaspora around the world commemorates the Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Circassian genocide, which lasted from 1763 to 1864. Over a century, the Russian Empire perpetrated genocide against the peoples of the Caucasus, resulting in the deaths and deportations of millions of innocents. The question of whether Russia has ceased or altered its practices of conquest remains rhetorical.

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Sources & references:

Watch this video about how Moscow deported people during the Soviet Union and how its successor, modern Russia, continues implementing the same policy.

A comprehensive look at Soviet deportations of Chechens and Ingush, from personal stories to international genocide recognition.

What led to the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944? Discover the Soviet Union’s motives and the lasting impact on the qirimly community.

and we will send you the latest news