Deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944

What led to the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944? Discover the Soviet Union’s motives and the lasting impact on the qirimly community.

Encyclopedia

Over the last 250 years, Crimea has experienced four waves of settlement renaming, linked to two Russian annexations. The occupying authorities have rewritten the ethnic names of the peninsula, erasing old names and replacing them with new ones to assert their dominance and rewrite history in their favor.

The momentum for renaming towns and villages in Crimea began in 1783, when the Russian Empire occupied the region for the first time. One of the first actions undertaken was renaming: the village of Ak-Yar became Sevastopol, and the town of Ak-Medzhit was renamed Simferopol. These names continue to be used today, as fewer Crimean Tatars have resided in the area since that time.

Following the mass deportation in 1944, Crimea underwent another large-scale wave of renaming. During this period, a significant number of districts, regions, and villages with Crimean Tatar names were renamed with Russian and Communist appellations in accordance with government decrees. In total, over 1,300 settlements on the peninsula were renamed, which constitutes approximately 90% of all settlements at the time. Most of these names remain in use to this day.

The forced eviction and renaming of ethnic villages in the Crimean Peninsula, especially those associated with Crimean Tatars, were significant aspects of a broader policy aimed at erasing identity and assimilation, enacted by Soviet authority. Such measures against Crimean Tatars and their settlements were part of a strategy to manipulate history, a tactic that the Russian Federation continues to employ. The campaign initiated after the 1944 deportation aimed to erase traces of Crimean Tatar existence in the peninsula, including the renaming of settlements and other geographical features, with the goal of severing the historical and cultural ties of Crimean Tatars to the region.

How did the renaming process work?

Soon after the last echelon carrying deported Crimean Tatars and other small ethnic groups departed from the peninsula, local authorities, under Moscow’s direction, hurriedly began to remove all ethnic elements from the peninsula’s map. This included Turkic names and traces of Greek, Armenian, German, and Bulgarian cultures. The most extensive renaming of Crimean settlements was carried out in three phases: in 1944, 1945, and 1948.

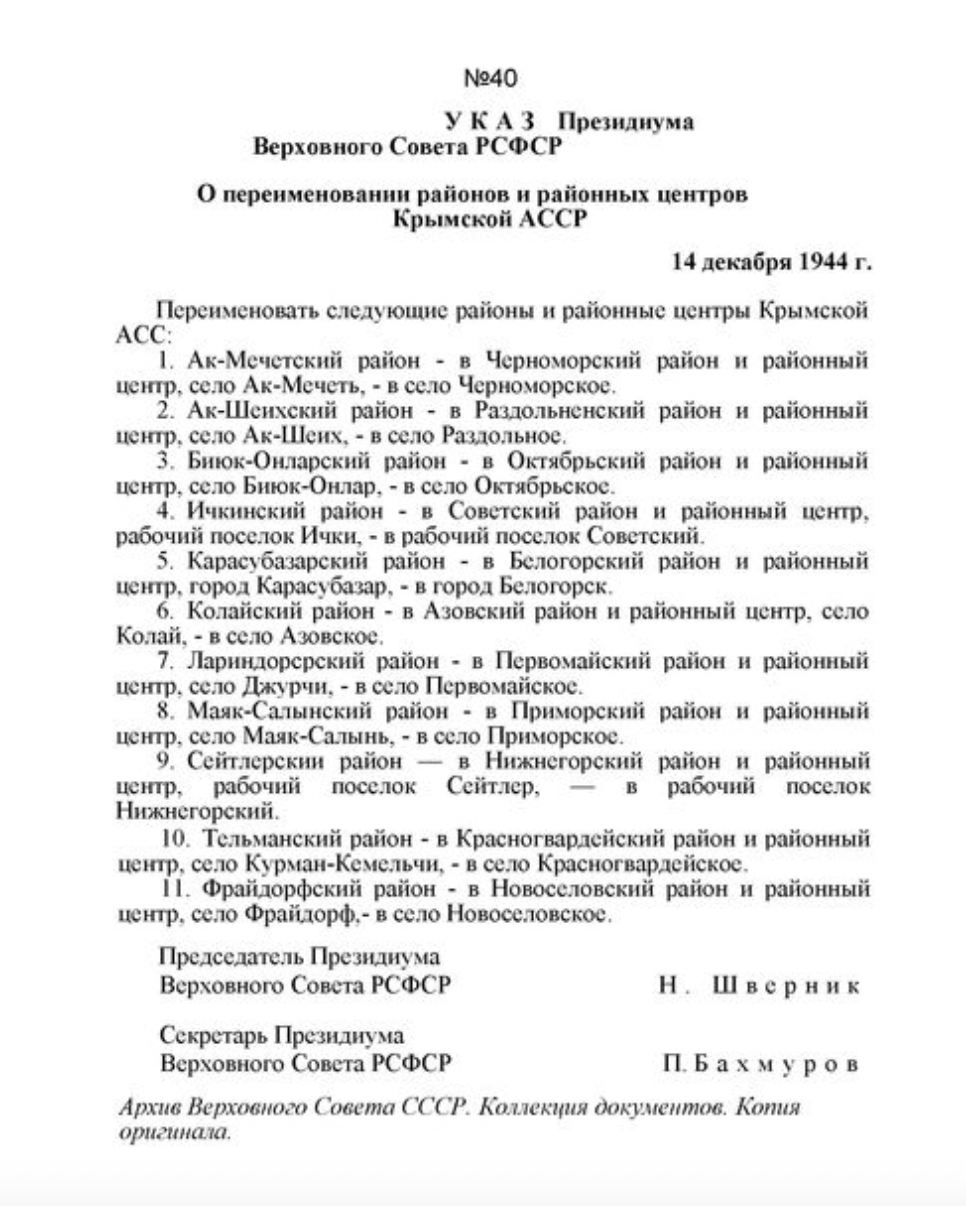

On December 14, 1944, a decree from the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic changed the names of 11 out of 26 districts and district centers in the peninsula that had Crimean Tatar or German roots. Subsequently, 22 local historical toponyms vanished from Crimea’s map. For instance, the Ak-Mechet district was renamed Chornomorsky, Ak-Sheikhsky became Rozdolnensky, Biyuk-Onlarsky transformed into Oktyabrsky, and Ichkinsky was renamed Soviet. The villages of Ak-Mechet, Ak-Sheikh, Biyuk-Onlar, and Ichki also received new names: they were rechristened as Chornomorske, Rozdolne, Oktyabrsky, and Soviet, respectively.

There was no one left to protest the renaming: those for whom the original names were native had already been evicted from the peninsula. For the new settlers, who were predominantly from the Russian RSFSR, the new names felt familiar.

This process marked the start of a long history of eradicating any traces of Crimean Tatar presence in Crimea. The Soviet authorities did not limit themselves to renaming; some villages were wiped off the face of the earth. Here are a few examples.

Subscribe for our news and update

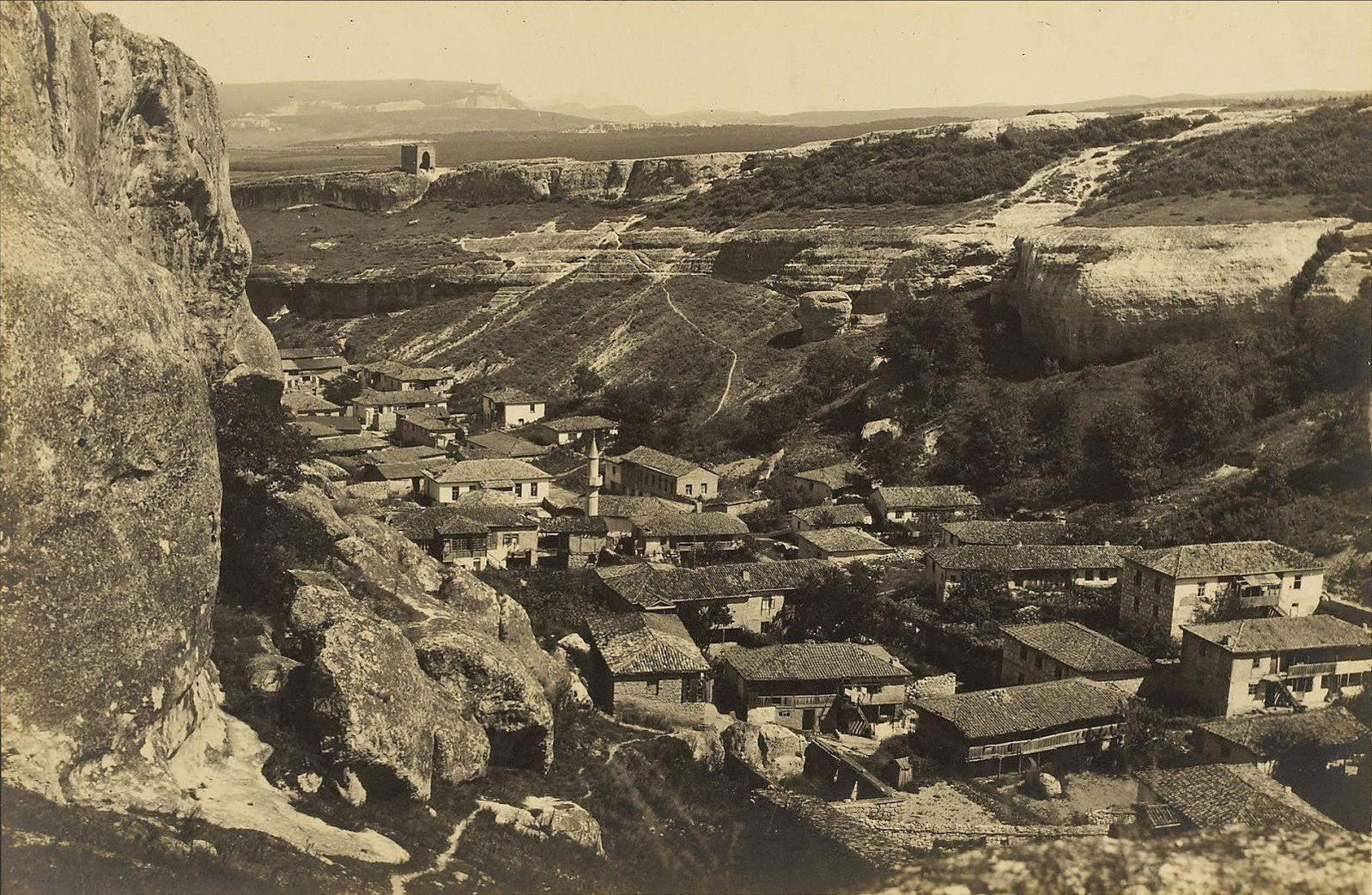

Cherkess-Kermen (Bakhchisarai District)

The village of Cherkess-Kermen, nestled at the bottom of a gorge and surrounded by mountains, was considered one of the oldest in the Crimean Peninsula. Archaeologists have discovered traces of settlements dating back to the 5th century AD. Nearby lies the medieval town-fortress of Eski-Kermen, which dates to the 6th century, and on the opposite side of the gorge is the Zamir-Koba cave, where evidence of ancient inhabitants from 10,000 years ago has been found.

The residents of Cherkess-Kermen constructed their dwellings by taking advantage of the natural features of the landscape. For instance, they situated stables, barns, kitchens, and cellars in the mountain caves, while the living quarters appeared to protrude from the mountains. Although the buildings of Cherkess-Kermen have long been ruined, traces of its former inhabitants still remain. On the cliffs, one can still see evidence of past structures, drainage systems, and supports for wooden beams.

According to the 1939 census data, 644 individuals resided in the village. However, in May 1944, the Crimean Tatars were deported to Central Asia. Following this eviction, Soviet authorities renamed Cherkess-Kermen to Kripke and encouraged people from various regions of Russia to resettle there. Despite attempts at forced ethnic cleansing and nominal revitalization of the village, settlers from Russia struggled to adapt to the mountainous terrain. The village of Kripke gradually became deserted, leading the Soviet authorities to dissolve it, while the sturdy stone buildings were dismantled for construction materials. Currently, a cattle farm operates on the site of the former Crimean Tatar village of Cherkess-Kermen, with its ancient history.

Beshui (Simferopol District)

The village of Beshui near Simferopol was historically significant, primarily inhabited by Crimean Tatars. Sources indicate that in the 19th century, there were five mosques in the village, and on the eve of World War II, it was home to 450 families, predominantly Crimean Tatars, whose children attended three rural schools.

During World War II, Beshui was a site of intense combat. The Germans executed locals for aiding the partisans and burned the village to the ground in the spring of 1944. After the peninsula was liberated by Soviet forces, the authorities destroyed the village once again.

Server Plaka, a native of Beshui, recalls: “In ’44, we were driven out. First, the Germans burned Beshui, and then we rebuilt the houses. It was like this – we moved into the house today, rested, and at night they came for us, loaded us up, and took us to Simferopol. There, we were put into a freight car, and we traveled to Bulungur in the Samarkand region.”[2]

After the 1944 deportation, the area became deserted, prompting the Soviet authorities to resettle it with collective farmers from different parts of the Soviet Union. Beshui was renamed Drovyanka, but after some time, ceased to exist as a settlement. The village was also dissolved because the settlers from other regions could not adapt to the climate of Beshui.

Since the restoration of Ukraine’s independence, indigenous residents gather annually at the site of their former village to honor the deceased and perform ceremonies.

Thus, the renaming of ethnic villages and towns in Crimea is part of a broader policy of Russian colonialism, which encompasses the forced erasure of the Crimean Tatar identity and the diminishment of this ethnic group’s visible cultural and historical presence on the peninsula. Following the deportation, the 1953 Soviet Encyclopedia removed most mentions of Crimean Tatars and their culture, except for a negative portrayal of them as bandits raiding Slavic lands.

The consequences of deportation and the subsequent policy of identity erasure have persisted for decades. Even after the lifting of the return ban in 1989, many Crimean Tatars have struggled to reclaim lost property and rights in Crimea, as well as to restore the ethnic names of towns and villages. The memory of these events continues to shape the struggle of Crimean Tatars for rights and recognition in the region.

Anastasiia Saienko, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

What led to the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944? Discover the Soviet Union’s motives and the lasting impact on the qirimly community.

Find out how Soviet authorities uprooted over 30,000 Greeks from their historical homelands in 1942 and 1944 without any justifiable reason.

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

and we will send you the latest news