Deportation of Ukrainians in 1947. Operation “West”

Discover how the Soviets systematically deported millions from the west of Ukraine, erasing villages and cultural landmarks.

Encyclopedia

The Soviet regime carried out multiple rounds of deportations in the Baltic States. In June 1941, hundreds of thousands were forcibly deported from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Yet, this was not enough to fully subdue these nations. In March 1949, another wave of deportations occurred, known as Operation “Priboi.” This operation targeted civilians in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, forcibly relocating them to Siberia and other isolated regions in the Northern USSR. A total of 94,779 people were deported, and 15% of them died during the journey [1, p. 315–316].

What drove the Soviets to deport such a large number of people again?

The reestablishment of Soviet control in the Baltic States between 1944 and 1945 set the stage for these mass deportations. Soon after regaining control, the Soviet authorities cracked down on those who had opposed them during the World War II, as well as intellectuals who resisted communist ideology. These groups were labeled as “class enemies” and “bourgeois nationalists,” terms that essentially covered anyone suspected of being against the Soviet regime [2, p. 137].

The first major post-war deportation was Operation “Vesna,” carried out on May 22-23, 1948. This operation led to the forced removal of 39,766 people from Lithuania. The primary targets were “the forest brothers,” partisans fighting for Lithuanian independence, as well as affluent individuals. Although the official reason cited was “dekulakisation,” the true objective was to eliminate private land ownership. [3].

Despite these efforts, the Soviet security services believed that the issue of integrating the Baltic States into the USSR was only partially resolved. Remaining “hostile elements” included not just those labeled as “bourgeois nationalists,” but also anyone critical of the new government and those who supported them. Joseph Stalin, the Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers, argued that removing these individuals would make it easier to implement collectivization, a process that was proving to be slow and challenging in the region [3].

The most devastating act of communist-led genocide in the Baltic States after World War II was Operation “Priboi,” a top-secret initiative by the USSR’s Ministry of State Security (MGB). Carried out on March 25, 1949, the operation was authorized by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Council of Ministers of the USSR. Lieutenant General P. Burmak, Chief of the Main Directorate of Internal Troops, was tasked with executing the operation as per Order No. 0068 issued on February 28, 1949, by the USSR MGB [4].

Both in 1941 and 1949, the deportations were sweeping, affecting all three Baltic republics simultaneously. Estonia and Latvia experienced two large deportations: one in June 1941 and another in March 1949. Lithuania, however, gaced additional rounds of deportations. Notably, in the fall of 1951, another mass deportation occured under the code name Operation “Osin.” This was the final mass deportation in a series targeting Lithuania and was aimed at “dekulakisation,” specifically against farmers who resisted collectivization and refused to join collective farms. The reason for the Soviet Union’s particularly aggressive stance toward Lithuania was the country’s highly organized resistance to Soviet rule [19, p. 281–282].

Key documents that shed light on this topic are housed in what is now the Russian State Military Archive in Moscow, originally part of the Main Department of the Military Forces of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. These archives provide crucial details about key individuals, the makeup of the security forces, and the logistics involved in the deportations [4]. Operating from 1945 to 1951, the Department of the Military Police of the NKVD in the USSR’s Baltic District was part of the Main Directorate of Internal Troops. This Directorate was under the command of the 2nd Division of the USSR MGB in Siauliai; the 4th Division of the USSR MGB in Vilnius; the 5th Division of the USSR MGB in Riga; the 63rd Division of the USSR MGB in Tallinn; and the 48th Division of the USSR NKVD Convoy Troops in Riga. These units were directly involved in Operation “Priboi.”

According to a directive issued on January, 27 by the Chief of the Convoy Troops of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, the 48th Division was responsible for escorting “special migrants” to far-flung areas of the USSR. A subsequent order of Colonel Kokhanovsky, the acting division commander, dated March, 4, 1949, specified that 108 echelon commanders from the 48th Division were to transport between 100,000 and 150,000 people from the Baltic States [4].

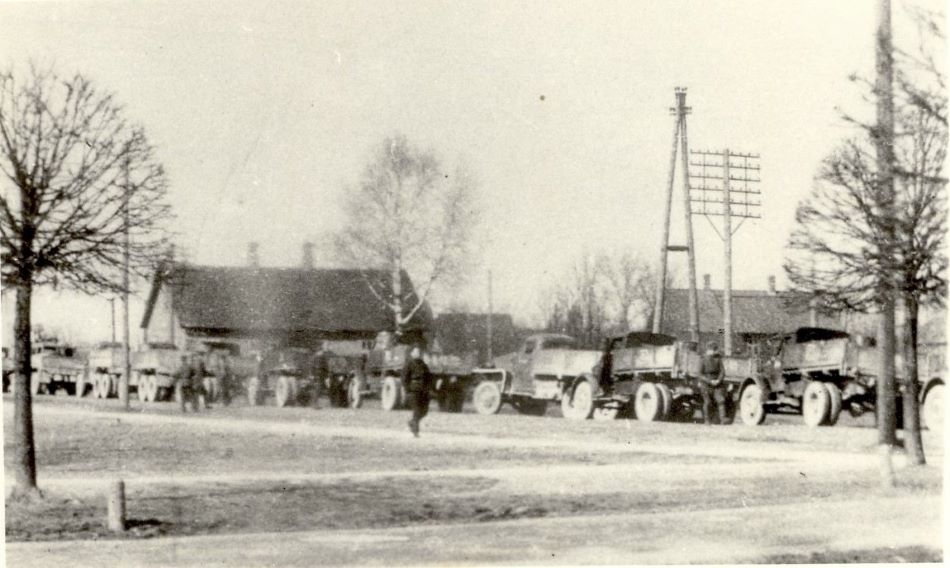

A column of military transport trucks in which deportees were taken away.

Estonia. Photo: 25 March 1949

Source: Järvamaa Muuseum [4].

Deported Estonians. Photo: March 1949 Source:

Private collection [4].

Operation “Priboi,” also widely referred to in historical accounts as the Great March Operation, commenced on the night of March 25, 1949. The forced deportations began at 4 a.m. in the Baltic capitals of Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius, and extended to outlying regions by 6 a.m. The operation was planned to last three days.

Here’s how it unfolded: Soviet military forces first arrived by car at the homes of those slated for deportation. The group leader, flanked by soldiers, would enter the home, identify its occupants, conduct a search, and then inform the head of the household about the impending deportation. Families had only a short time to gather their belongings. Once packed, Soviet soldiers escorted them to designated loading areas. Party members and Soviet activists who were part of the operation remained to inventory the deportee’s left-behind property, which was then confiscated. The deportees were subsequently taken to collection points, usually railway stations, where they were loaded onto trains [5]. From there, they embarked on a long journey to their forced new residences.

In Estonia, the operation mobilized more than 2,000 operatives from Soviet security services, nearly 6,000 military personnel, and over 8,000 party workers. The MGB of the Estonian SSR planned to deport 7,540 families, totaling 22,326 individuals. From March 25 to 29, 7,488 families – 20,535 people, including 4,579 men, 9,890 women, and 6,066 children – were forcibly sent to Siberia on 19 trains [6]. The operation fell short of its target as 1,791 people managed to evade capture. However, the punitive communist authorities conitnued to pursue them, launching a full-scale hunt that lasted for several months [7].

One individual who remembers the March 1949 deportation is Veronika Ariva (Saar). She, along with her mother and two brothers, were on the deportation lists. Her father had already been imprisoned for delivering a eulogy at the funeral of his friends who were part of the Forest Brothers, a partisan resistance group fighting for Baltic independence. He was held Tallinn’s Patarei prison before being deported to the Soviet Far East, specifically the island of Sakhalin.

She recounts the events of March 1949 this way: “The operation was executed in complete secrecy. The villagers were unaware. On the morning of March 25, our neighbour’s grandmother came to warn us. She was shaking with fear as she told us that people were being deported to Siberia by train, and we were on the list. She urged us to flee. My brothers were 12 at the time, and my mother had just baked bread. The boys grabbed some food and left, agreeing to meet up with their mother later. My mother and aunt had different surnames than those on the deportation list, so she took me by the hand, and we went to the neighboring village where our friends lived. We told them everything. Soon after, we saw people in Soviet military uniforms driving into the village. It was clear they were coming to deport people. My mother hid us in large special boxes at the edge of the village, and my aunt brought blankets to keep us warm. We stayed in the forest for two weeks. Later, my aunt learned that the village council had decided not to deport those who remained, as the trains had already left. We returned home, but the sense of danger never left us” [8].

Another victim of mass deportation was Hilja Heinsoo, born in Estonia in 1932. On March 25, 1949, Hilja and her parents were deported to the Irkutsk region. Prior to their deportation, the family had been labeled as kulaks, leading to heavy taxation. On the day they were deported, people were first gathered at a school in the village of Lasva before being taken to the Vyr railway station. During the train journey, Hilja was responsible for food supplies in the carriage. At station stops, she would go out to get food, escorted by soldiers, who were generally friendly towards the deportees and even agreed to deliver letters to their remaining relatives in Virumaa [9].

In Latvia, Operation “Priboi” mobilized 3,300 operatives, 8,313 internal troops from the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, and 9,800 Soviet army soldiers. The operation utilized 31 freight trains to deport people. A total of 13,624 families, or 42,975 individuals – primarily rural residents – were deported. They were labeled by the Soviet authorities as “kulaks” or allies of the “forest brothers.” Of those deported in 1949, 183 died en route, and 4,941, or 12% of the total, died in exile. The irreversible loss of life due to the deportations amounted to 6,500 people, or 0.35% of Latvia’s total population at the time [10].

Photos from the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia showing victims of the March 1949 deportation. Photo: Museum of the Occupation of Latvia [11].

Edvards Peredistis, a staff member at the Museum of Occupation in Latvia, describes the 1949 deportation: “To move the deportees, 31 trains with cattle wagons were assembled. I can’t say how many wagons each train had, but it’s evident that people were crammed in. These conditions were in direct violation of Soviet decrees, which called for wagons designed for human transport. In reality, there were no such amenities. At best, there was a bucket or a hole in the carriage to serve as a toilet” [11].

A deportation train at the Stende railway station. 25 March 1949. Photo: Jānis Indriks, from the archive of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia (reproduction: Andrejs Strokins). [4].

In Lithuania, Operation “Priboi” was executed with particular involvement from local Soviet authorities and Communist activists. These individuals actively collaborated with Soviet repressive agencies in carrying out deportations. Their role included identifying the homes of villagers labeled as “kulaks” and families opposed to Soviet policies since the regime’s return in Lithuania in 1944. The operation mobilized over 10,000 operatives and thousands of military personnel, resulting in the deportation of 33,496 people from Lithuania [12, p.181]

Monument to repressed Lithuanians. Memory Square, Tomsk

(42-44 Lenina Ave.). [15].

The total number of people deported from the Baltic States in March 1949 included 25,708 men, 41,987 women, and 27,084 children under the age of 16. In all, 94,779 individuals were forcibly removed from their homes to Siberia and Russia’s Far East [4]. These aren’t just numbers; they represent tens of thousands of lives irrevocably shattered by the crimes of the Soviet repressive system. Moreover, these figures are staggering when considered in relation to the overall population of the Baltic States.

The destinations for deported citizens from the Baltic States varied: Estonians were primarily sent to the Krasnoyarsk Territory and Novosibirsk Oblast, with some going to the Irkutsk and Omsk Oblasts in the RSFSR. Latvians were mostly deported to the Amur, Omsk and Tomsk Oblasts, while Lithuanians were sent to the Tomsk Oblast [14].

The sand-filled cemetery of deportees in Tit-Ary (a village in the Khangalas ulus of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Russia).

Source: Museum of the Occupation and Liberation Struggle. [13].

The Soviet authorities systematically and deliberately sought to crush the national identity of Baltic citizens, suppress any aspirations for independence of these countries forever, and either deport or kill those who resisted.

Deportation was intended to be permanent; Soviet leaders never planned to allow these individuals to return home. It wasn’t until after Stalin’s death that returning became a possibility, and even then, it was a difficult process. The Soviet regime didn’t acknowledge the deportations as a crime until the late 1980s, instead labeling them as “forced measures”.

These actions should be recognized as acts of genocide against Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. The imperative for the future is to preserve the historical memory of these events and prevent similar tragedies from happening again. This is especially relevant as Russia is currently repeating the same tactics in Ukraine against Ukrainians.

Vladyslav Havrylov, author

Oleksii Havryliuk & Maksym Sushchuk, editors

Subscribe for our news and update

Discover how the Soviets systematically deported millions from the west of Ukraine, erasing villages and cultural landmarks.

A look back at the Soviet-era deportations in the Baltic states, chronicling the stories of those who endured this dark chapter in history.

The Soviet occupation authorities drew different reasons for each ethnic group to be eliminated from the territory of Ukraine, but the procedure was always the same — forcible deportation. In this article, we will draw upon the extraction of ethnic Germans from Ukraine.

and we will send you the latest news